Pan Am in the Arctic: Following the Viking Trail

Sea Face of Cornell Glacier (250 ft). Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library*

Sea Face of Cornell Glacier (250 ft). Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library*

Crossing the Atlantic by Air

The big guns of World War One were barely silenced when dreams for transatlantic aviation began to sprout wings. In May of 1919 New York hotelier Raymond Orteig offered his prize for the first flight to link his two hometowns of New York and Paris (a prize claimed by Charles Lindbergh eight years later). Just successfully crossing the ocean would be an accomplishment. But the 1919 flights of the US Navy’s NC-4, and Alcock and Brown’s Vimy, lit a slow-burning fuse.

Capturing even a tiny fraction of ocean-liner passenger traffic could add up to commercially viable numbers. But for practical commercial purposes, in the 1920’s and early ‘30’s, with the limited range and capacities of contemporary aircraft, the potential of bridging the ocean would demand intermediate stops to refuel. The distances between the US, Newfoundland, Bermuda, the Azores, and Europe offered possible routes, but the gaps precluded carrying real payloads for the airplanes that were available at that time.

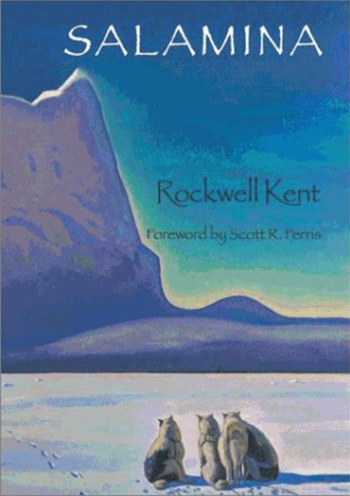

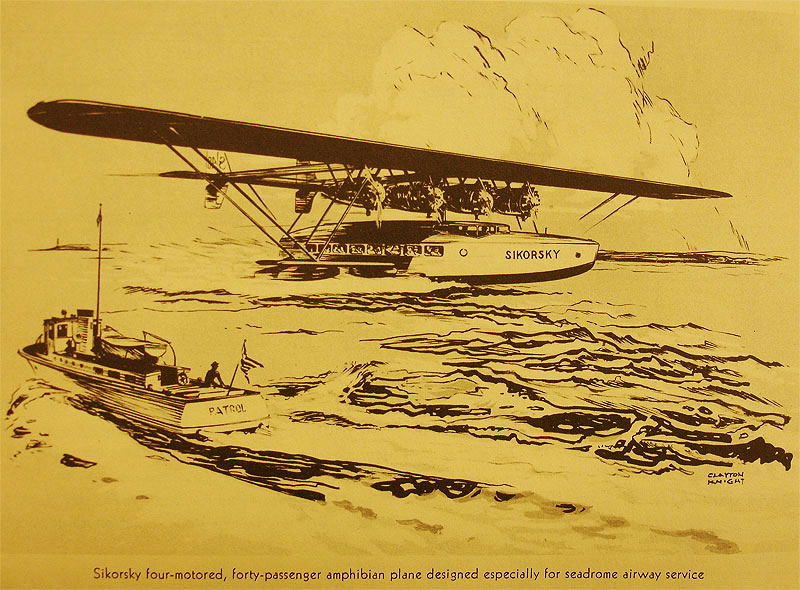

One ingenious – if far-fetched – concept involved building massive, anchored artificial islands, floating strategically along a transatlantic route. Robert Armstrong’s “Seadrome” plan was imaginative but not very practical. (But the idea lived on and finds application in today’s floating deep-sea oil drilling rigs.)

Concept drawing of Sikorsky S-40 Flying Boat. From Armstrong Seadrome Brochure, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Harry Frantz Collection, 1930

Concept drawing of Sikorsky S-40 Flying Boat. From Armstrong Seadrome Brochure, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Harry Frantz Collection, 1930

Seadrome Anchored with Flying Boats Overhead. From Armstrong Seadrome Brochure, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Harry Frantz Collection, 1930

Seadrome Anchored with Flying Boats Overhead. From Armstrong Seadrome Brochure, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Harry Frantz Collection, 1930

The Viking Trail

The most compelling option for transatlantic routes seemed to jump off the map: Newfoundland – Greenland – Iceland – Europe. What was not so clear were the actual environmental and meteorological considerations of the routes, particularly on Greenland. While Iceland was a better known environment with a long-settled population and a willing government, Greenland was another place entirely. A protectorate of the Danish government, Greenland was mostly a blank slate as far as possible air operations. Little of a practical nature was known about its climate, environment, and local geography.

Early “Greenland”

A thousand years earlier, Eric the Red tried to entice followers to the world’s biggest island by tagging it with the somewhat disingenuous name of “Greenland.” But even the most enthusiastic settlers lured by the attractive name found it a tough place to eke out an existence. By the start of the fifteenth century, they were gone.

The Thule people migrating eastward from Alaska reached Greenland shortly before the Norse left, and with their superior arctic technology (dog-sleds), were able to make their new home a going proposition. They lived a nomadic existence, depending on hunting to make a living. It was a sparse and tough life-style, demanding endurance and exquisite understanding of the natural environment.

Resurging Interest - Aviation

Greenland – barren, cold, and wind-swept, with the world’s largest ice-sheet outside of Antarctica’s -- was of little attraction to outsiders in the centuries that followed. But by the early 1930’s the growing prospect of transatlantic commercial air travel engendered new interest on the part of airline strategists from both sides of the ocean. Flying shorter over-ocean distances between North America and Europe using Greenland and Iceland as stepping-stones was a powerful incentive to explore and research the possibilities.

New York Herald Tribune Front Page detail, Wednesday, December 20, 1933

New York Herald Tribune Front Page detail, Wednesday, December 20, 1933

Juan Trippe’s Careful Planning

Even a gambler like Juan Trippe wouldn’t place his bets on air operations in Greenland without a lot more understanding of what Pan Am would be getting into. So Pan Am brought in famed Arctic explorer Dr. Vilhjalmur Stefansson for consultations regarding Arctic aviation possibilities, a field that he pioneered. Learning more about actual conditions would be critical and Pan American adopted a three-pronged strategy to research the problem: By air, sea, and land.

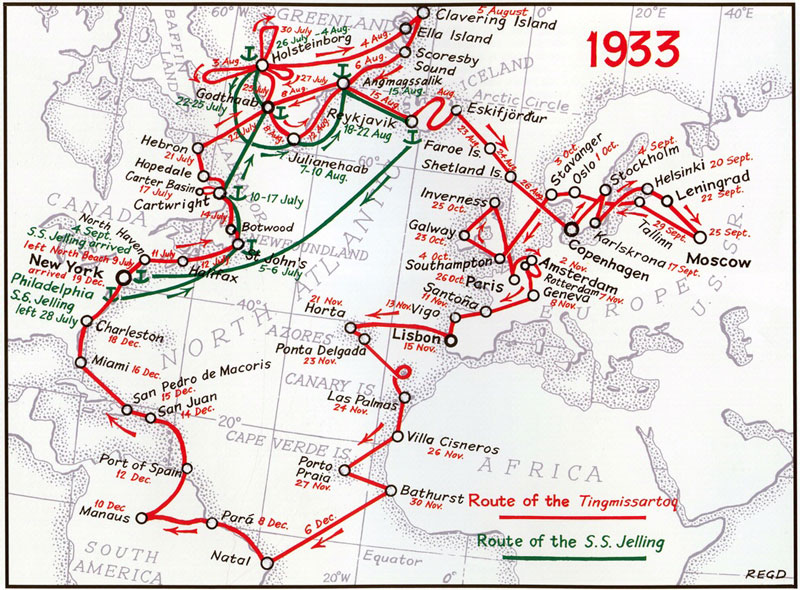

Map of Pan Am’s Jelling Expedition, courtesy R.E.G. Davies

Map of Pan Am’s Jelling Expedition, courtesy R.E.G. Davies

Charles & Anne Morrow Lindbergh Exploration, 1933

One high-profile approach was to again enlist the services of the airline’s eminent technical adviser, Charles Lindbergh. Just as with their trip to Asia in 1931, Lindbergh and his partner / spouse, Anne Morrow Lindbergh would climb into their Lockheed Sirius “Tingmissartoq” to survey the possible routing to and around Greenland as part of a more complete Atlantic research trip. (The aircraft name was Inuit for “one who flies like a bird”.)

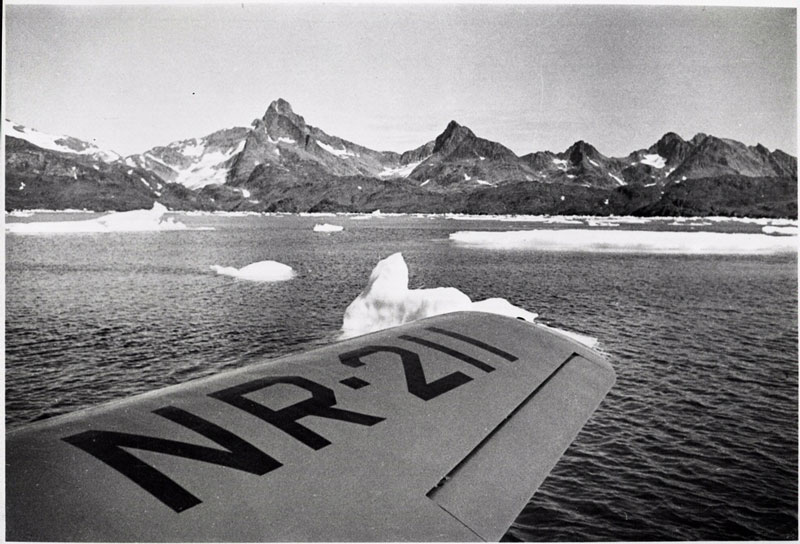

Photo 1933 from Lindbergh’s Lockheed Sirius. Anne Morrow Lindbergh took this photo of icebergs near Angmagssalik, Greenland. Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Date: 1933, Photo Number: NASM A-45256-F

Photo 1933 from Lindbergh’s Lockheed Sirius. Anne Morrow Lindbergh took this photo of icebergs near Angmagssalik, Greenland. Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight Gallery, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Date: 1933, Photo Number: NASM A-45256-F

The Lindberghs would spend weeks crisscrossing the island by air before moving on to Iceland and then Europe, followed by flights to Africa, the Cape Verde Islands, and the Azores before returning to the Americas via the South Atlantic. From the air the Lindberghs would observe and record winds, temperature, and fog conditions, as well as taking aerial photographs of the coast.

The SS Jelling Expedition, 1933

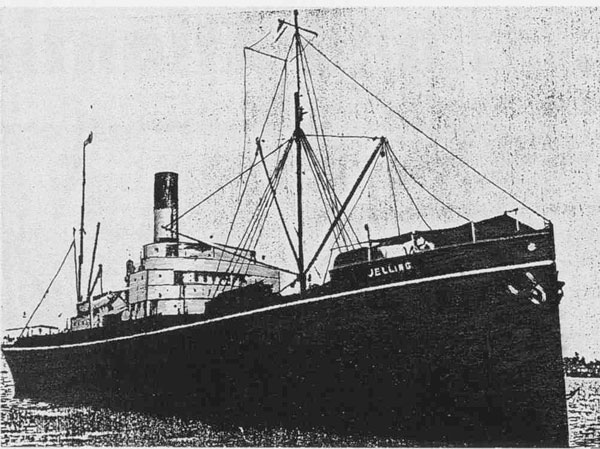

The SS Jelling, 1933 still photo, courtesy of R.E.G. Davies

The SS Jelling, 1933 still photo, courtesy of R.E.G. Davies

The second approach (closely linked to the Lindberghs’ efforts) was to charter the Danish steamer, the SS Jelling. This expedition, under the command of Canadian explorer/aviator Robert Logan (who had worked for Pan Am in South America) would shadow the Sirius, providing fuel and support, but would also conduct a parallel research project by sea, observing weather conditions, making maps of possible airport sites, taking scientific measurements of ocean depths and currents, and mapping harbors too.

Pathe newsreel showing the SS Jelling and the Lindberghs

Tough Sledding: The Land Expeditions

The third prong of Pan Am’s efforts involved several land expeditions, conducted in collaboration with other entities. These were solidly in the tradition of Arctic exploring, pitting small groups of hardy souls against the rigors of an unforgiving environment. As events would prove, it could be a life-or-death proposition.

East Greenland Expedition with Pan Am, 1932-33

One expedition was the Pan American East Greenland expedition to the southern section of the east Greenland coast in 1932-1933. The expedition included four men, funded by Pan Am and the British Royal Geographic Society, to look into the possibility of building an Arctic airbase. This group gathered knowledge for sighting possible airports in the interior, as well as general weather conditions for a twelve-month period. Tragically, their leader Gino Watkins lost his life on the expedition while hunting for much-needed seal meat. Read more: http://www.freezeframe.ac.uk/resources/expeditions/arctic/east-greenland-expedition-pan-am-1932/east-greenland-expedition-1932

University or Michigan - Pan American Greenland Expedition, 1932-33

Another expedition was the University of Michigan – Pan-American West Greenland journey to the Upper Nugsuak Peninsula of Northwest Greenland coast, also in 1932-1933. This exploration surveyed the west coast of Greenland in an area near the Cornell Glacier, only sparsely surveyed in 1896 and on which little information was available. The expedition tracked weather balloons for study of upper air currents and was ultimately very successful, providing complete records of physical and meteorological conditions of the west coast and coastal waters. Directed by geologist Dr. R.L. Belknap, the expedition prepared a special report for Pan Am, which included a thorough picture of the conditions in Greenland, with information from several earlier UM expeditions to the more southerly part of Greenland’s west coast.

Abandoned Moraine North Cornell Glacier (Tarr) 1896 Cornell Glacier, Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library *

Abandoned Moraine North Cornell Glacier (Tarr) 1896 Cornell Glacier, Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library *

In true Arctic exploration tradition Dr. Belknap had to make a heroic trek alone on skis, from his camp 9,000 feet up on the Cornell Glacier, after a lonely two-month solo scientific study during the summer of 1933. Expected support from his team members failed to arrive on time due to blizzard conditions. With supplies running out, he was forced to set off by himself to return to the base camp at the coast. Although his companions finally met up with him as he struggled back, they were all forced to take drastic measures to survive. Several of their faithful sled dogs died from sheer exhaustion, and were fed to the rest so that the party could manage the trek back to safety.

“Belknap Relates Attainments of Greenland Trip, Started Home September 18 after Two and A Half Years of Work,” The Michigan Daily, Sunday December 3, 1933, Vol. 44, Issue 60

“Belknap Relates Attainments of Greenland Trip, Started Home September 18 after Two and A Half Years of Work,” The Michigan Daily, Sunday December 3, 1933, Vol. 44, Issue 60

https://digital.bentley.umich.edu/midaily/mdp.39015071755941/405

Rockwell Kent, 1934

Pan Am supported more expeditions to Greenland as the decade progressed. In 1934, the airline lent financial support to an expedition, led by explorer/illustrator Rockwell Kent, who surveyed and mapped the northerly west coast. According to a report from the National Gallery of Art, in his book Salamina:

Cover of Salamina, a book about his life in Greenland by Rockwell Kent

“Kent thanked the General Electric Company and Pan American Airways Corporation for supplying the expedition with cigarettes, a radio set, food, and “six dozen quarts of emasculated fruit juice,” and also proposed naming ice caps after the companies, in mock tribute, on the hand drawn map published with his account.”

1935-36 Greenland Observations

In 1935-36 Pan American Airways also maintained – at the request of Danish government - two Danish officers who spent a year in separate Greenland locations to observe flying conditions.

Politics and Aviation Technology: A Road not Taken

For all this effort, the development of the “Viking Trail” across the northern Atlantic was soon a matter of historical hindsight for Pan Am. Having ordered both the Sikorsky S-42 and Martin M-130 flying boats in late 1932, the airline would have much longer-range aircraft by mid-decade, making the stepping-stone route less critical. And by 1936, the even longer-range Boeing B-314 was on order for delivery in 1938 (although actual delivery was delayed to the following year).

But the real obstacle to using the “Viking Trail” was political. On the western side of the Atlantic the use of Newfoundland – a critical jumping-off place -- was now off the table, since the formerly autonomous British “Dominion” had reverted to the status of a Crown Colony following violent political unrest due to the Depression. Now Newfoundland’s affairs would be decided in London. Until the Brits were prepared to fly a reciprocal service using British aircraft, there would be no American airline transatlantic service making use of British territory.

On the other side of the “pond,” Pan Am’s concession with Iceland to use the island as a stepping-stone had lapsed, and although a new arrangement was under discussion by 1937, by then the increasingly strident Nazi regime in Germany was making it clear that they would look very unfavorably on such a deal, and so the Icelanders thought it best to defer granting a new concession.

Cornell Glacier, 1896.Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library *

Cornell Glacier, 1896.Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library *

Epilogue

So for all the sub-arctic exploration and planning for air routes using Greenland and Iceland, the bold efforts of the 1930’s would never yield practical benefits. Of course, in just a few years, the world would radically change, both in terms of aviation technology and international politics. The constraints of years past would be nothing more than interesting history, and the thrilling pioneering efforts that pitted humans against the elements would be regarded as the impressive achievements they were, irrespective of any practical benefits to aviation they were meant to provide. Planes would fly miles above Greenland, while their occupants could casually gaze below with little inkling of the hardship and danger once faced by those who worked and sacrificed to create an air route along the “Viking Trail.”

*Tarr, Ralph Stockman & Cornell University Library (2014). Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland from the Ralph Stockman Tarr expeditions (1896; 1905-1911). Cornell University Library. doi.org/10.7298/X4M61H5R