WHEN 2001 REALLY WAS THE FUTURE

Sir Arthur C. Clarke on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Photo Courtesy of Arthur C. Clarke Foundation

Sir Arthur C. Clarke on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Photo Courtesy of Arthur C. Clarke Foundation

In 1968, author and visionary Arthur C. Clarke gave an exclusive interview to Charles Power, which was published in that year’s Feb-March edition of Pan American’s Clipper Magazine. We are pleased to reproduce it here. The man who conceived of communication satellites long before they were actually put into orbit had some other fascinating ideas about life in the future, and we’re happy to share them with you.

Life in the 21st Century: An Interview with Arthur C. Clarke

by Charles Power

Photo: Pan Am Historical Foundation Clipper Newsletter, May 1968

An invitation to make a $10 million film with the director of "Dr. Strangelove" might give some people pause, but not Arthur C. Clarke, whose middle name might be candid—or caustic. The dean of Sci-Fi writers and past chairman of the British Interplanetary Society is not easily impressed—even with such things as his considerable readership in the Soviet Union or his fan mail from Russian scientists. Clarke is more interested in thus-far elusive Russian royalties. "The money is accumulating somewhere, he comments; "I want to find out where it is and spend it."

Clarke has a serious side, too, as befits the winner of the Franklin Institute Gold Medal for the original concept of communications satellites. Of man's role as a world citizen, Clarke says, "I rather like Marshall McLuhan's description of earth as developing into a ‘global village'.'’

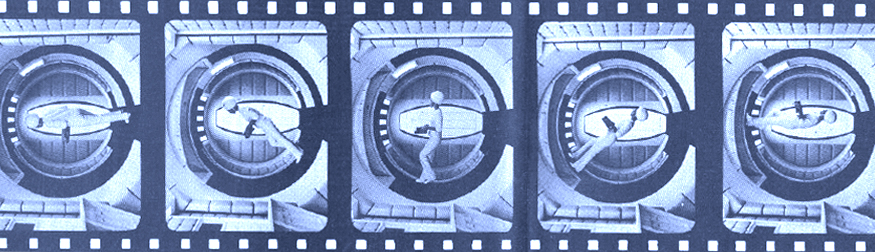

Talented director Stanley Kubrick, an omnivorous reader, began thinking and reading about the future and what the space age means to mankind. Having read Clarke’s stories and novels, it seemed natural the two should team up on a space film. They started with a short story of Clarke's and generated both the novel and screenplay for "2001." Both were done as a team, with credits being split as screenplay by Kubrick and Clarke based on a novel by Clarke and Kubrick.

"2001" is not a message film. Says Clarke, "I've always liked to quote Sam Goldwyn’s 'If you’ve got a message, use Western Union'." With plot concentrated on a two-and-a-half year trip from the moon through outer space, Clarke and Kubrick have tried to achieve reality— in terms of what will actually be happening in 2001. "We've avoided the cliches, I think," says Clarke. "This is the sort of thing that could and probably will happen."

"There are no villains in the story," says Clarke. "Just man against the universe— that’s all the conflict you need."

Kubrick and Clarke made their epic as contemporary as possible.

"As an example of the realistic approach of the film," Clarke explains, "you do see a small amount of advertising. We see various brand names, because this gives a feeling of real life so often lacking in science fiction films. Take the appearance of Pan Am stewardesses, for example, aboard the fifty-passenger aerospace plane in opening sequences of '2001'; this is practically a commuter flight to the moon—people recognize the stewardess and feel they can identify with the situation."

As to whether people in 2001 will still believe in advertising, Clarke says that "they have for the last 35 years, and we can assume they will for the next—after all, 2001 is only that far in the future."

Trips to the moon and other interplanetary points at one time raised eyebrows. A few years ago Clarke’s article in a national magazine covered typical activities that man might pursue upon reaching the moon. Irate readers responded asking if this was a joke. "Soon afterwards," Clarke recalls, "the President of the United States announced that the moon was the prime goal of the American space effort."

How fast will man travel in the 21st century?

Clarke sees no real need for much advance beyond the currently planned supersonic transports operating at about 2,000 mph. He feels that ground-effect, or hover-craft, will be more practical. He predicts that by the end of the century, thousand and ten- thousand ton vehicles will cross land and sea and negotiate difficult terrain such as swamps, ice fields and coral reefs.

Photo: Pan Am Historical Foundation Clipper Newsletter, May 1968

With satellites and spaceships whirling around in the atmosphere, will the 21st century produce severe traffic congestion in the skies?

“This is a possibility,” says Clarke, “though I personally feel that the sheer volume of travel will not be frightening. Ultimately, communication may develop to the stage where we won’t do much business traveling. I can imagine a time when even a brain surgeon can live in one place and operate on patients all over the world through remote-controlled artificial hands, like those used in atomic energy plants. Actually, there is a contest between communications and transportation, but there will always be pleasure transportation. What is going to happen is that pleasure travel will increase enormously and business transportation will decrease enormously. And I can't imagine too much time for pleasure.

“People at the moment are hypnotized by the enormous progress of space travel. But at present, it’s a fantastic situation comparable to filling an ocean liner with several thousand passengers and then throwing the ship away at the end of each trip. What we must now work for are reusable vehicles and revolutionary new energy systems. Actually, the inflight cost of space flight is ludicrously low, a few pennies per pound to orbit. The amount of energy needed to lift a man to the moon is about 1,000 kilowatt hours—and that costs only 10 to 20 dollars. The difference of nine zeros between this and the space budget is a measure of our present incompetence.”

Clarke predicts that by 2001 there will be tourist flights to the moon. “Space is a benign — or at least a neutral — environment, it’s not ferociously hostile like the ocean depths or the gale-swept Antarctic.' Ordinary people will probably think no more of going to the moon than they now do of jetting across the Atlantic ocean.”

In addition to man’s exploration into space, is there any substance to tales of travel from the opposite direction?

“There are thousands of UFO’s (unidentified flying objects), but no little green men from space,” says Clarke, who has said that if you’ve never seen an UFO, you should be ashamed of yourself. “It’s very unlikely that there are men as we know them anywhere in the universe,” says Clarke. “The universe is full of intelligence — and I'm sure we're pretty low in the pecking order. But I also think it’s unlikely that anywhere in space is anything you would mistake for a man, except on a very dark night. It’s amazing how people's descriptions become distorted. You would never mistake a chimpanzee for a man, but try to describe the difference and you'd end up with the conclusion that they're identical.” Clarke considers the chance of a real space-ship evading discovery in this age of radar about the same as that of a dinosaur hiding itself in the streets of Manhattan.

Photo: Pan Am Historical Foundation Clipper Newsletter, May 1968

Other Clarke predictions for the future: increased leisure (six-day weekends), the disappearance of grey hair (extra vitamins), synthetic foods such as the experimental variety tested by Kubrick, who said it "looked like dog biscuit and tasted like ham,” and perhaps a cure for death itself.

In the field of communications satellites Clarke has played the role of a true prophet, although the financial fruits have not been spectacular. His pioneering article. “Extraterrestrial Relays’’ appeared in Wireless World in 1945. For this article, originating one of the most commercially valuable ideas of the century, Clarke was paid $40. Twenty years later, he described his feelings about this in an ironic subtitle, “How I Lost a Billion Dollars in My Spare Time," and musing on the lost dollars, Clarke imagines what even one minute's royalty on the telephone, TV and radio traffic of the communications satellite would come to. “It would have been pleasant, in my old age, to have gone cruising among the asteroids in my private space-yacht. But there are other and more realistic moments when I think of all the soap operas and laxative commercials that will soon be bathing Earth from pole to pole, and a far different future begins to take shape in my mind. Perhaps I shall spend the rest of my life trying to prove that communications satellites were invented, not by Arthur C. Clarke, but by another man with the same name.”

Science fiction, both in novel and magazine form, is big business. Clarke, author of over 100 short stories and some 40 books, is aware that despite its popularity, Sci-Fi is frowned upon by some members of the scientific community. His comment on this, upon receiving the distinguished UNESCO Kaligna Prize for science writing, was that "although many scientists believe 90 percent of science fiction is rubbish, they ignore the fact that 90 percent of all fiction is rubbish."

Photo: Pan Am Historical Foundation Clipper Newsletter, May 1968

Will science fiction still be needed by 2001 — when it's actually happening out there in space?

“Science fiction flourishes on science as a frontier,” says Clarke. “ As technology advances, so does the frontier of science fiction. I think the new frontier will be out among the stars; there’s no limit. All sorts of new and strange things will have been discovered by then.”

As to whether Clarke will himself go to the moon:

"Oh, I take it for granted I'll go someday, but obviously not in the pioneering stages. I'll probably go on a magazine commission — something that happened in one of my novels, by the way, a science fiction writer making his first space flight. Yes, it's strange somehow, but I seem to have said all these things before — and now they're coming back to haunt me.”