July 20th, 2024 marked the 55th anniversaryof the first landing on the Moon in 1969 by the astronauts of Apollo 11

One of the technical achievements to come from the Apollo program - the Inertial Guidance System, or INS - was the basis for the new onboard navigation system which was being installed on the then-brand-new Boeing 747.

But Pan Am’s involvement with America’s Space Program went much deeper. Just a few months before the launch of the mission to put Americans on the Moon, some very interesting particulars about just how tightly Pan Am was woven into the workings at the Kennedy Space Center - and beyond - were described in an article by George Dill, in the Pan Am Clipper of November 1, 1968. The event was the very first manned Apollo mission to go into orbit - Apollo 7, launched on Oct. 11, 1968.

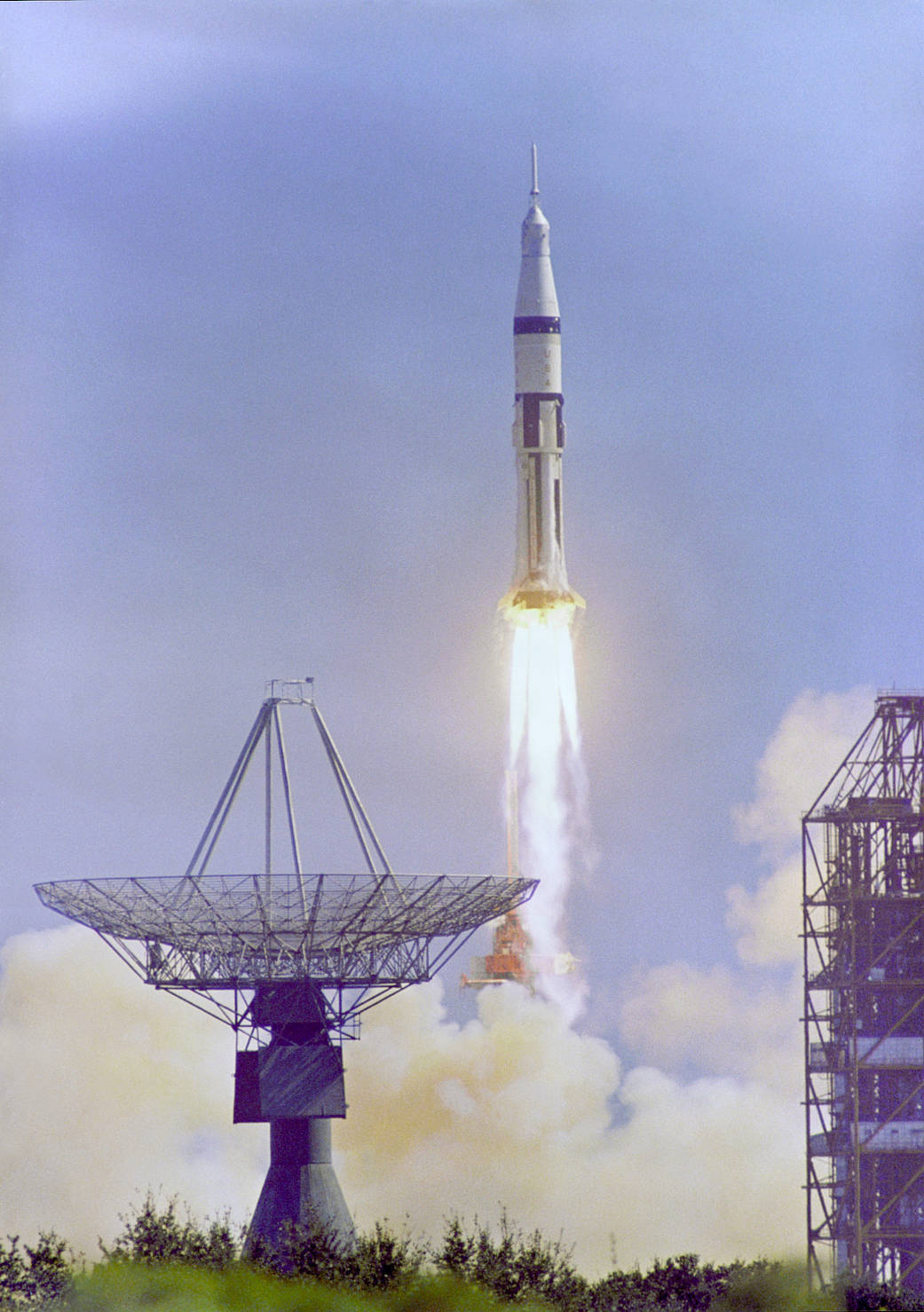

Apollo 7 Launches on October 11, 1968. The Apollo 7 Saturn IB launched from the Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 34 at 11:03 a.m. October 11, 1968. This image show the tracking antenna on the left and a pad service structure on the right. Image Credit: NASA

BEHIND THE APOLLO 7 SPACE FLIGHT

by George Dill

(from the "Pan Am Clipper" November 1, 1968)

Pan Am’s Aerospace Services Division (ASD) is in its 16th year as prime contractor at the Air Force Eastern Test Range that reaches 10,000 miles from Cape Kennedy deep into the Indian Ocean. Pan Am’s 5,000 ASD staff has the responsibility for planning, engineering, operating, and maintaining the range: from storage to handling and delivery of missile propellants, to planning instrument techniques giving voice and direction to man in his quest of the stars.

Cape Kennedy - Long before the Apollo 7 mission lifted into space on Oct. 11, the Pan Am Launch Complexes crew at Complex 34 considered themselves the luckiest here: they were directly supporting the Apollo program to put a man on the moon.

For Pan Am’s Aerospace Services Division, work on the Apollo program began long before Captain Walter M. Schirra Jr., USN; Colonel Donn F. Eiselle, USAF; and Walter Cunningham, a civilian astronaut, began their 10- day, 20-hour and nine-minute orbital journey.

The job began when the requirements to use Complex 34 for a manned launch were made known and ASD advanced-planning engineers studied Eastern Test Range support problems, then furnished the guidelines for any needed Range development.

Instrumentation systems, such as radar, would track the vehicle from liftoff to pinpoint the location and velocity required to determine if the astronauts could go into orbit.

Telemetry would send back information both on the astronauts and vehicle.

Engineering sequential and documentary photos were to be provided. Many would be seen on network television during the early stages of the flight.

Pan Am engineers provided the system engineering for radar, telemetry, and optics.

ASD engineers provided the system engineering for six specialized aircraft for Apollo support. Each has an eight-foot antenna in the nose; one is outfitted with an ALOTS (Airborne Long- range Tracking System) optics which provide photos of a missile up to 50 miles away.

The ARIA (Apollo Range Instrumentation Aircraft) provided real-time communications and telemetry recording for the Apollo Spacecraft while in orbit over remote areas of the South Pacific.

Pan Am engineers also provided complete ships’ system engineering support for several specially-equipped Apollo tracking ships. Pan Am engineers drew up the specifications for the ships’ modifications, equipment and instruments needed.

Pan Am engineers made studies of the missile propellants explosives and helped set safety standards and plan the launch site locations. Basic operating and maintenance procedures were completed for the launch complex.

As a result of this and other groundwork, all was ready for the booster and spacecraft arrival. The Saturn/Apollo vehicle arrived by air on a landing strip at the Cape. Pan Am Fire/Security people supported and guarded the vehicle during its trip to the launch pad. (Pan Am also provides all the maintenance support, air conditioning, power, water, sewage disposal, cafeteria and even mobile canteens at the Cape.)

Pan Am people assisted in the assembly and checkout of the vehicle on the launch pad. ASD propellants people assisted in fueling the “bird,” as it’s known, and Pan Am pad safety personnel checked the ordnance installation. At the top of the “bird,” the spacecraft was enclosed in a “white room” or “super clean” room maintained by Pan Am. This was necessary throughout the life of the spacecraft so that dust and dirt wouldn’t interfere with the astronauts and their equipment.

All was ready for launch. Pan Am medical and disaster teams stood by. The countdown proceeded.

From Cape Kennedy to the Indian Ocean, Pan Am manned their equipment and consoles on remote island bases and ocean range vessels. Each base is a small self- contained city, operated and managed by Pan Am.

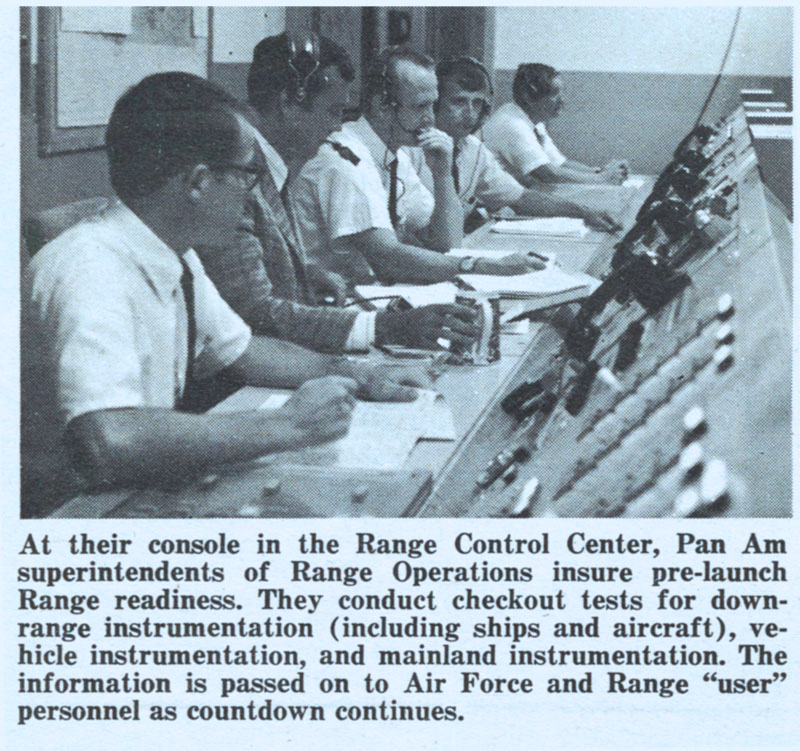

At his console at the Cape’s Range Control Center, the Pan Am Superintendent of Range Operations coordinated all Range Operations and all Range support with the Air Force and NASA people to authorize launch. The Eastern Test Range was “green and go.” The space business of saying “A-OK” was really originated by Pan Am Range operators.

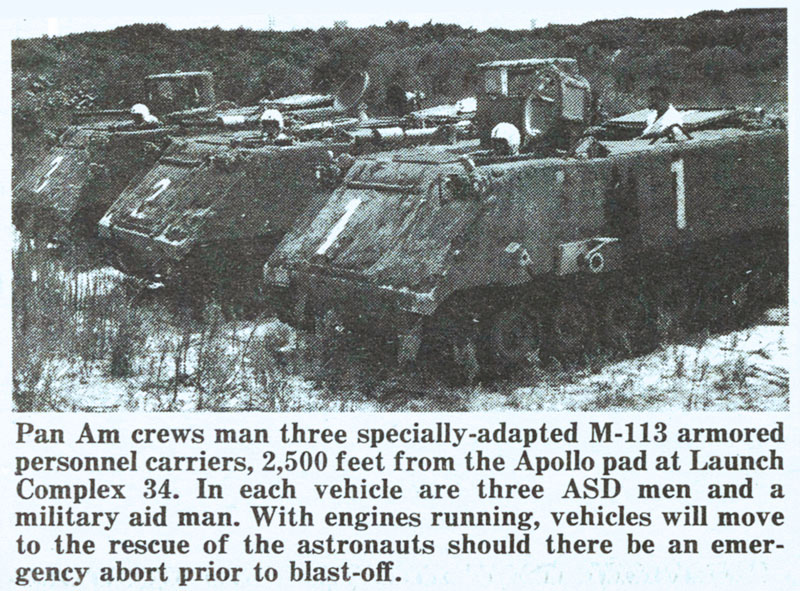

The Pan Am Pad Egress Team was in position 2,500 feet from the launch pad. Highly trained, the team stood ready to rush to the pad in specially-covered M-113 tanks to rescue the astronauts should the missile have “aborted” on the pad.

During the final minutes of the countdown, work at the Cape came to a virtual standstill.

All attention was directed toward that steel mountain known as the Saturn IB and its human cargo—astronauts Wally Schirra, Walter Cunningham, and Donn Eisele.

There was a three-minute hold. The count resumed and, at 11:03 a.m., the Saturn IB, predecessor to the Saturn 5 moon rocket, lifted off, its eight H-l engines furiously belching fire across Complex 34, providing a total thrust of 1.6 million pounds.

In about 2.5 minutes of operation, the thirsty “bird” burned about 42,000 gallons of fuel and 67,000 gallons of oxidizer to reach an altitude of about 33 nautical miles at engine cutoff.

Separation of the IB stage came at two minutes, 24 seconds into the flight. The J-2 engine of the second stage cut in two seconds later.

The engine produced a thrust of 200,00 pounds for about 7.5 minutes of operation. It burned 64,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and 20,000 gallons of liquid oxygen. All was going well.

Insertion of the spacecraft into orbit came at ten minutes, 25 seconds into the flight. Apollo 7 was now at an altitude of 141.7 miles, 1,175.2 miles downrange, streaking through the heavens at 17,- 240.4 miles per hour.

On Oct. 22, 1968, the Apollo 7 crew is welcomed aboard the USS Essex, the prime recovery ship for the mission. This was the first Apollo splashdown and, therefore, the first three person 'landing' for NASA. Left to right, are astronauts Walter M. Schirra Jr., commander; Donn F. Eisele, command module pilot; and, Walter Cunningham, lunar module pilot. In left background is Dr. Donald E. Stullken, NASA Recovery Team Leader from the Manned Spacecraft Center's Landing and Recovery Division. Image Credit: NASA

The flight was called “101% successful,” paving the way for a manned circum-lunar flight later this year. Some officials were optimistic enough to predict a manned landing on the moon in June, 1969.

The astronauts were flown from the recovery ship USS Essex, on Oct. 23, to Cape Kennedy’s landing strip. Hundreds of Cape workers turned out to greet the space triplets.

Capt. Schirra commented to the crowd: “We left rather suddenly; it’s good to be back.”