Ground Controlled Approach in Gander

Part 1

A Very Serious Game of Hide and Seek

By Robert Pelley. Mr. Pelley is a long-time military and aviation enthusiast who grew up in Gander, Newfoundland – the “Crossroads of the World.” He served as officer in two of Canada’s finest regiments: The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and also with the Royal 22e Régiment, the famous French-speaking “Vandoos.” We are indebted to him for the use of this material. Used by permission (This story includes some additional material by Frank Tibbo and Doug Miller)

Ground Control Approach: The Background

In 1935 Dr. Robert Watson-Watt of the United Kingdom determined that "radio detection and ranging" (radar) was feasible and the first highly secret operational British station was built in 1937. This technological advance was the forerunner of the use of radar in Air Traffic Control (ATC) today. In late 1941, feasibility experiments in blind landing were carried out at Quonset Point Naval Air Station, Rhode Island, USA. On 22 December 1942, navy Ensign Griffin made the first Ground Controlled Approach at Quonset Point, talked down by Lt. Aurand.

This initial GCA radar was developed by the Gilfillan Company. The U.S. Army quickly contracted with Gilfillan, and the U.S. Navy with Bendix, to produce the first ATC radar sets (AN/MPN 1). The US Armed Forces used its GCA system during the war with much success and after the conflict, many who used it urged its use by civil aviation, while the US Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) favored another system, the “Instrument Landing System” (ILS). For a time the use of GCA in Gander was therefore in doubt.

GCA Arrives in Gander

It is generally believed that the first time GCA came to Gander was in late 1946. This is in fact incorrect.

The USAAF base Gander unit history clearly shows that a GCA unit was operated in Gander in July 1945. The duration of this operation is unknown but the summer and fall of 1945 witnessed the gradual reduction of base personnel as operations fizzled out. Surplus supplies and equipment were shipped to Harmon and Pepperrell.

The unit history gives the following description of the arrival and set-up of the unit in July 1945:

‘‘Ground controlled approach at Gander was activated during the month. Fourteen men, in addition to the one officer and one man already at the station, arrived and work was begun July 5th.Operation on the runway is from 0700 to 1700 daily, with an alert crew standing by the rest of the 24 hours. July 5th and most of the6th were used in giving the Unit a fast check-over and tune-up, and the first trial run was made on the 6th by General Farman's plane. Up to the 18th, most of the time was given to maintenance checks and repairs. The Unit arrived by rail and boat and the trip had jolted many of the adjustments out of line. During the check period, twenty-three runs were made for the purpose of orientation of pilots and crews and checking the alignment of the Unit. On the 18th the first emergency run was made. ”

The coordination with routine operations also had to be organized. The base history goes on to explain:

“ The GCA team reported that liaison with the Canadian authorities at Gander had been excellent."

GCA anticipating a difficulty in stacking a large flight of planes, made arrangements whereby the RCAF Tower operators would stack planes on the range and ladder them down, enabling GCA to feed them into the field traffic pattern one at a time. The Tower monitors GCA frequencies and relays messages when necessary.

Improvements made on the CCA equipment include the installation of a speaker so that the Tower could be continuously monitored on a low frequency. The setting-up of a warning light by one of the doors of the truck allows any outside observers to listen to the operational conversation. A maintenance semi-trailer obtained from Air Corps Supply is being converted to GCA purposes. In progress was the painting of the GCA operating truck to make it less a navigational hazard. The top half was painted yellow on July 31st. "International Orange” is the color planned for the bottom half. ”

Pan Am gets GCA

This military operation in was followed by the better-known civilian operation starting 1946.

The Corner Brook Western Star of 21 March 1947 had the following headline:

RADAR SYSTEM INSTALLED AT GANDER AIRPORT. Now Possible to Make Safe Landings At Night Or During Fog Or Snow Storms.

“Pan American World Airways announced this week that all major trans-Atlantic airlines are using the radar system for bad weather landings that Pan American World Airways had installed at Gander.

More than 300 military and commercial transports have been directed to uneventful landings at that airways’ cross-roads by operators of GCA (ground control approach) since the system was ready for use eight days after arrival at Gander, it was pointed out by Pan American at its Atlantic headquarters at La Guardia Field, N. Y. Most of the landings have taken place at night and many during snow flurries in zero temperatures.”

The Western Star went on to say that this GCA unit, consisting of a truck and trailer unit, arrived in Gander on 28 November 1946 and made ready for use on 6 December, then flight tested by the Army and brought in the first commercial airliner, a Pan American Clipper, on 17 December.

Pan American invited other airlines to use its GCA service (identified as “Blue Jay” for air-to-ground communications) and to share in the cost, estimated at $40,000 for the first year. Below is an extract from a letter sent by Pan Am to American Overseas Airlines (AOA) on 17 December 1947, inviting them to join. A similar letter was also sent to Trans World Airways (TWA), Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS),TransCanada Airlines (TCA), Sabena, Royal Dutch Airlines (KLM), British Overseas Airlines (BOAC) and Air France (AF).

“It is anticipated that the service tests on the GCA equipment will be completed within a few days, and that advisory services can be made available on or before January 1, 1947. Unfortunately, it is not possible to give a precise indication of the costs of this service to the individual airline, as it is not known how many participating companies there will be. For your guidance, however, it is now indicated that there will be at least six participating companies, and that the total cost to be divided between the participants, prorated as indicated in the agreement, will not exceed $40,000 for the period January 1st to June 30th, 1947.”

The Western Star reported that AOA, BOAC, SAS, KLM, and TWA had agreed signed on.

It is however more than surprising that Sabena, who had lost a DC-4 airliner with loss of 26 out of 44 passengers and crew across Gander Lake only three months earlier, decided not to become a founding member. They strangely decided to let their pilots to use the GCA service on an on-call basis, only if they judged it necessary. Each on-call service, if completed, would have cost $125 at the time, with this cost increasing over the years.

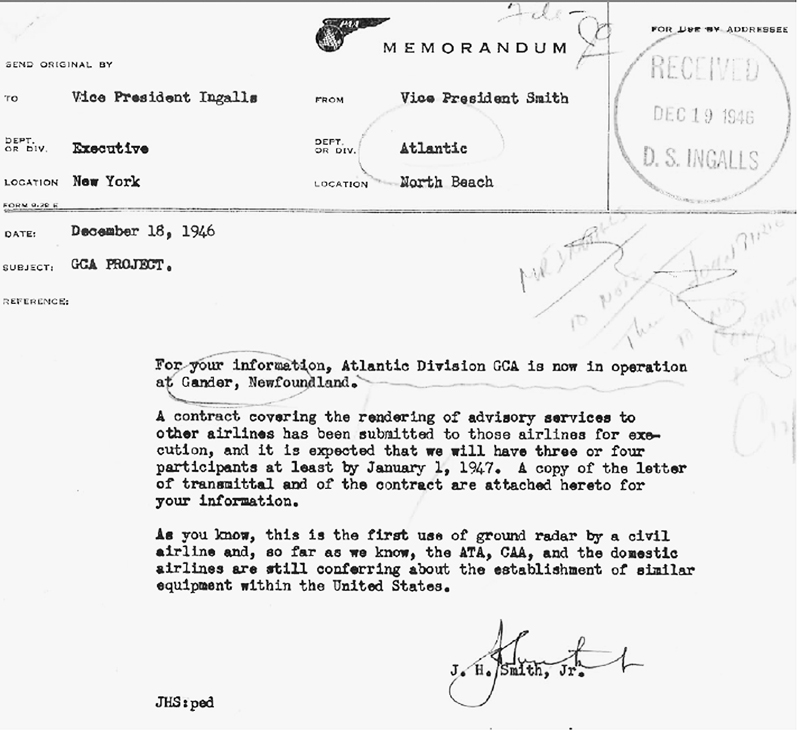

This Pan Am memo, dated 18 December, 1946 can be considered the first statement of GCA being in operation in Gander, which then became the first civilian airport in the world to see GCA used on a commercial basis:

In the spring of 1947, the CAA started in-service testing of Gander GCA, as well as at Washington and Chicago, who had received GCA equipment shortly after Gander. On 9 April, 1947, the CAA gave its official approval of the use of GCA for commercial flights, authorizing its use by Pan Am in Gander.

The Human Side of the Story

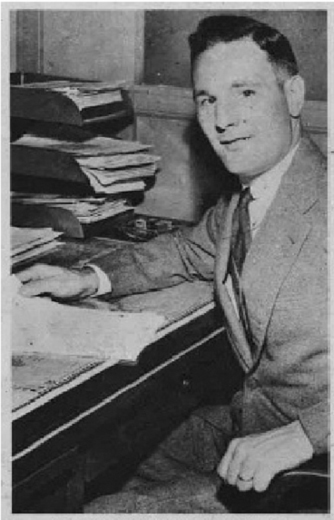

But as the case of most “corporate” events, there is always in the background a human story, where some one carried the ball and made things happen. In this case, as reported in the Newark Sunday News (New Jersey, USA) on 31 August 1947, it was a chap by the name of Philemon R. Dickinson. Dickinson had been a Marine Corps First Lieutenant and a member of the initial Marine GCA unit in the Pacific. Chuck Aldrich and two members of the Gander GCA were members of the same unit.

Philemon R. Dickinson: Marine, Princeton Graduate and Pan Am Employee

Philemon R. Dickinson: Marine, Princeton Graduate and Pan Am Employee

Dickinson returned to his prewar job with Pan Am, but with a new mission, that of “selling” GCA. This took months – but finally he got the go-ahead. The US Army leased one of its 400 or so “obsolete” units to Pan Am for 1$ a year - and were glad to get rid of this now mothballed equipment!

Dickinson quickly rounded up a crew of ex-servicemen to go to Gander and within 10 days after arrival, had the equipment set up and running - even though the wintery conditions in Gander at the end of the year were not quite those of Iwo Jima in the South Pacific.

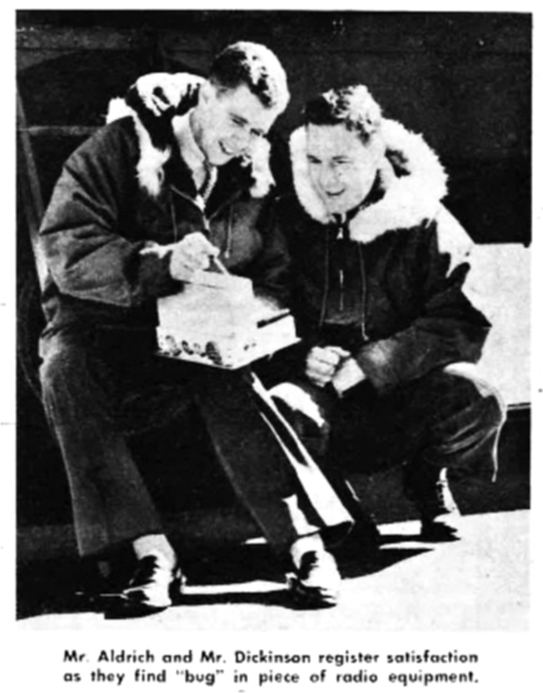

Below is a photo of Dickinson and his buddy former Private Aldrich. The caption tells all.

“Talking Them Down”

Gander GCA filed reports with the CAA on a regular basis, giving the number of flights by airline, noting the name of the pilot and if the flight was a tactical flight (requiring real assistance) or practice flight (where GCA was used but not necessarily required by weather conditions). Any “talk-downs” that were not completely routine were described, as in the example below with an airplane from BOAC:

May 6. Speed Bird GEK. Captain May. When turned on final on heading 180 plane tracked rapidly left. He was given a heading of 210 which corrected him gradually to course. When he reached the QDM he was given heading 208 which brought him down the QDM from 3 1/2 to 2 miles. At 2 miles he began drifting right and headings of 205, 203, 200, and finally 195. None of these headings brought him back toward course, so he was pulled up at 3/4 mile when he was 500 feet right and 100 feet above the glide path. There was evidently a cross draught at this point for all succeeding runs during the night had a similar drift. However, in the following approaches we were ready for it, and caught it in time. Captain May pulled up at our request, made another circuit, and was brought down the middle very satisfactorily. This run was very successful.

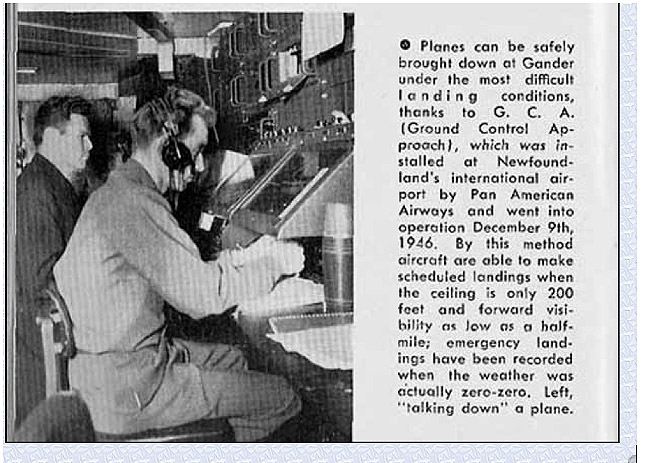

Photo (r.) GCA Operators at work in their trailer

Photo (r.) GCA Operators at work in their trailer

Another typical problem was making radio contact, as can be seen with this AOA example, where there was interference between two radio frequencies:

May 22. Flagship 915. Captain Banfe. We encountered serious radio interference within the trailer and the plane could not read our instructions satisfactorily. Captain Banfe called the tower at 6 miles on final and said he was taking over visually, but would try communications with us again. We again established communications and attempted to continue approach since 915 was in good position at 4 miles. However, he could not read us continuously and so was advised to land visually. This interference, we believe, was caused by feed-through when (frequencies) 126.18 and 118.1 are used simultaneously.

This type of radio problem almost caused a possible crash several days later with an RAF airplane, a Lincoln, which is basically a souped-up late-war version of the well-known Lancaster:

“RAF RE-414

On May 23, I947, BOAC dispatch advised that they had an RAF plane, RE-414, Lincoln, arriving at Gander at 0603Z. The ceiling was 900 feet and forecast to go down to 300 feet by the time of his arrival. They asked us if we could assist him in landing at Gander. Since we were in operation during that time we promised our assistance.

His ETA was advanced to 0630Z and no position reports were obtained during the latter part of his flight. The various stations were alerted and asked to assist in locating the plane. At about 0740Z we picked him up at 28 miles in the vicinity of the NE leg of Gander Range. At that time he called the tower. However the plane did not receive the tower’s instructions and there ensued 20 minutes of frantic calls between the control tower, Blue Jay, and RE-414 with no success. The range finally made contact with him and he was instructed to switch to 3105 kcps and call us for instructions. Again contact could not be established as he could not read us on that frequency, although we could read him loud and clear. After a number of unsuccessful attempts he returned to range frequency.

In the meantime he was circling in the vicinity of the NE leg of the range. Since we had failed to contact him on HF or VHF we were at a loss on what to try next. During this time he made no attempt to get into the field. We tuned another similar HF transmitter to 3105 kcps and gave him a call using this transmitter. He immediately read us “loud and clear". The contact was established at 0817Z when he was 28 miles NNE of the field on an outbound course. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Hoyle, declared that it was "definitely an emergency at this time". We assumed control and advised him to return to the field via the range leg. He advised us that be could not fly the range while in communication with us. Therefore we assigned him a heading to bring him back over the field and brought him through a pattern and down the centerline of runway 18. He landed at 0829Z. He was very grateful for our services. He said he wasn’t particularly worried about flying around the area because he knew we would establish contact with him sooner or later.”

On 29 May 1947, TM McGrath, Gander airport operations manager announced a reduction in GCA minimums to a 300 foot ceiling. Two days later, according to the same report, the number of all approaches for all carriers was 837.

The Demands of Delicate Electronics

But the GCA operators didn’t just sit around chatting to airplane crews. The GCA unit that Pan Am brought to Gander “had already been through a war” in the Pacific Theatre of Operations and by virtue of its history and its complexity required constant monitoring and maintenance. If the GCA went down, the consequences could be fatal. For those who like the technical aspects, below is a report covering maintenance during May 1947.

BLUE JAY

Gander, Newfoundland

June 1, 1947

Maintenance Report # 6

The following equipment failures were encountered during the period from May 1 to 31, inclusive:

VHF receiver #1 out of order. Found VT-169 (1208)

with open filament. Replaced tube from spares. Cost- $1.00

Channel “B” search crystal became weak causing attenuation of signals. Replaced, crystal (1N21) from spares. Cost - $0.33

Channel "A” modulator arcing and high voltage overload relay kicked out. Found V-7 (715C) arcing. Replaced the tube from spares. Cost - $28.00

VHF #3 receiver inoperative. Found. VT209 (12SG7) with an open filament. Replaced tube from spares. Coat -$0.89. Replaced harmonic generator tube (9002) and RF amplifier(9003) both of which had low mutual conductance. Cost - $1.90

#2 4KV power supply (PP22) failed. Found rectifier (2X2) with open filament and a short in transformer (T~2). Replaced these from spares. Cost - (2x2) - $0.90. (T-~2) -$8,75

Some of the cost figures are approximate values. Most of them however are taken from catalog figures.

The-unit was in operation for a total of 218.7 hours during this period. A total of about 216 hours were spent In operation and about 2.7 hours spent in preventive Maintenance.. There was no lost time during this period due to equipment failures.

Anyone interested in electronics will know that this is quite a variety of problems in a very small space: VHF receivers go down because of bad tubes; power supply transformers shorting out; a crystal diode going out of whack, etc. This requires both excellent diagnostics and equally good repair skills - obviously they knew their job, with less than three hours in the month on required maintenance. Over the same period four years later, in 1951, over three dozen radio tubes had to be replaced instead of just four. Maybe this equipment was starting to show its age.

Smooth Talking

One story collected for an article on “Blue Jay” on the website of the Gander Airport Historical Society by Frank Tibbo involved operator "Obe" O'Brien.

“He was a particularly smooth talker and a super operator. He was bringing in an aircraft early one morning that had been flying approximately twelve hours and the crew was pretty darned tired. Maybe it was O'Brien's voice that caused them to relax too much because both pilots fell asleep at the controls. He kept telling them they were below the glide path but the aircraft didn't respond. Finally O'Brien took drastic action. He yelled in his headset: "Goddammit if you don't pull up you're going to crash!" That did the trick. The pilots responded immediately and after it was all over, the shaken pilots joined O'Brien for a thankful cup of coffee. O'Brien used to laugh about it, after, saying, ‘You know I could lose my licence for swearing 'over the air', I hope nobody reports me.’ Nobody did.”

GCA vs. ILS

The future of Gander’s GCA was always unsettled. As mentioned at the start, the US Civil Aeronautical Administration wobbled between GCA and ILS. In Gander, the Canadian government was very much pro-ILS. During the discussions in the early 1950’s concerning a possible runway extension, the addition of ILS was a major concern as can be seen below, in this extract from a letter from the Canadian Department of Transport (DOT) to Pan Am as early as 5 February 1951:

“You will know that our Department had planned to extend runway 09-27 at Gander to a length of 3600 feet. Moving the railroad is necessary to such a project and it is now estimated that the costs of this item will be far in excess of the funds appropriated by the Canadian Government. There is a real possibility, therefore, that the project may be deferred.

If moving the railroad does prove to be beyond our immediate resources we plan to extend run-way 14-32 in lieu, it would also be our intention in continue the ILS installation on runway 09-27 at its present length in order to achieve the highest utilization and the best coverage.

The International Air Transport Association and all those companies interested in Gander are being advised and asked for comments. We would welcome any comments you might care to make, particularly with respect to the ILS installation without the extension to runway 09-27.”

The reply from Pan Am further illuminates the situation:

“In reply to your letter of February 5th, concerning the extension of runways at Gander Airport, the following are our recommendations:

1. Our first choice of runway for extension Is 14-32.

2. Since apparent technical difficulties prevent installation of ILS on runway 14-32, our second choice is is the installation of ILS on runway 09-27. The effects of this decision would allow operations under instrument conditions during the extension of runway 14-32, without interference throughout the fortcoming season; whereas, if extension of 09-27 and the installation of ILS continued simultaneously, we feel that higher weather minimums will be required.

3. In conjunction with the installation of ILS on runway 09-27, we recommend that every consideration be given to the installation of a high intensity approach light system, as the two go hand in hand. Our choice would be a modified Calvert system.

We thank you for this opportunity of presenting our recommendations, and we would gratefully appreciate knowing your finalized plans.”

The final upshot was that in 1958 the Canadian DOT installed its own system and the GCA unit initiated by Pan Am was decommissioned.

Alas, time and technology wait for no man!

One post-script to the “Blue Jay” story: Challenging meteorological conditions notwithstanding, the friendly Newfoundlanders working in this small community must have made working there something better than a hardship posting, as several “Blue Jay” staffers ended up marrying local women.

Continue to Part 2: Ground Controlled Approach in Gander: Blue Jay, the Operations, the Equipment, the People, by Robert Pelley

Mr. Pelley is now working on a longer article on Pan Am’s history in Gander. His website http://bobsganderhistory.com/ provides a superlative source of information on the birth of trans-Atlantic civilian air travel and ferry and anti-sub operations in the North Atlantic during World War II, as well as the fascinating subject of “Old” Gander in general.