JULY 1933

July 5, 1933

“Offices in the Sky”

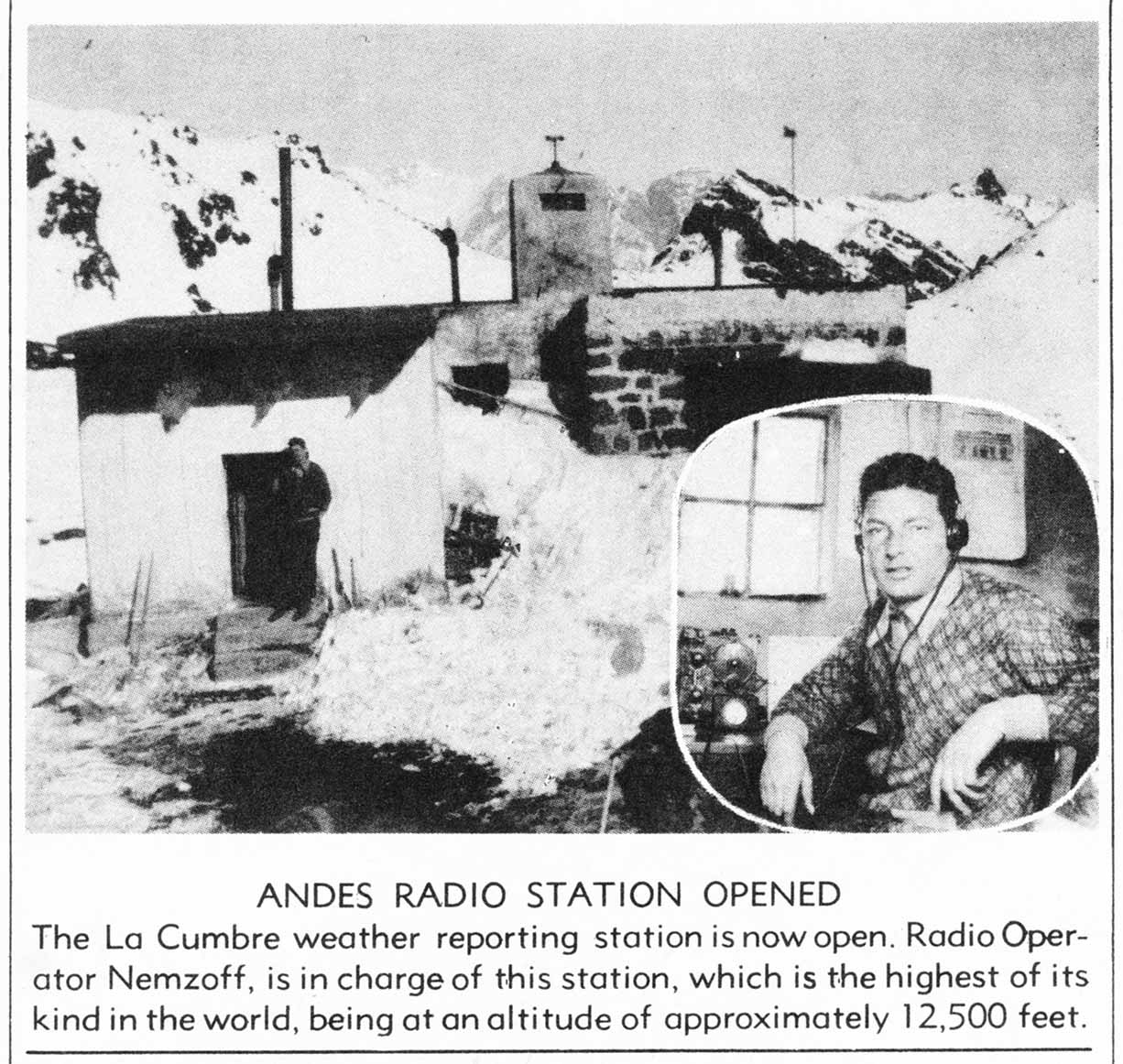

Photo: Detail of the Chrysler Building aerial view, Gottscho Colleciton Library of Congress, circa 1930.

Photo: Detail of the Chrysler Building aerial view, Gottscho Colleciton Library of Congress, circa 1930.

New stationery dropped throughout the Pan American Airways system, starting July 1, 1933, because Pan Am had a new corporate address: 135 East 42nd Street, New York, New York (a.k.a., The Chrysler Building). The company had outgrown its Chanin Building office space and President Trippe secured the Chrysler Building’s 58th and 59th floors (just below the building’s four iconic stainless-steel eagle gargoyles). Along with Pan Am, the Chrysler Building housed two on-the-rise businesses, Chrysler Corporation and Texaco, Inc., making its tenant list as impressive as its exterior design.

The relocation provided movers and employees few challenges: materiel and personnel simply crossed the Lexington Ave./East 42nd St. intersection’s southwest corner to its northeast corner. And the new digs were as nice as the prior’s: The Chanin and Chrysler Buildings sported beautiful Art Deco lobbies, limited access, high-speed elevators, and easy flow to the city’s public transportation system. The July 1933 move allowed Pan Am to cluster its central offices and grant President Trippe and other Board Members who joined the three-hundred-member Cloud Club (66th-68th floors) access to a top-tier restaurant and male-only social space that afforded exclusivity without venturing outside.

135 East 42nd Street would remain Pan Am’s corporate address for thirty years when in 1963 Pan Am moved three blocks northwest to its final home, 200 Park Avenue.

Sources:

"Pan American World Airways," Vol. 4. No. 4, p.1, July 1933, (Univerity of Miami Special Collections). https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/40877/rec/4

July 12, 1933

“Captain Keeler’s Dirty Bird”

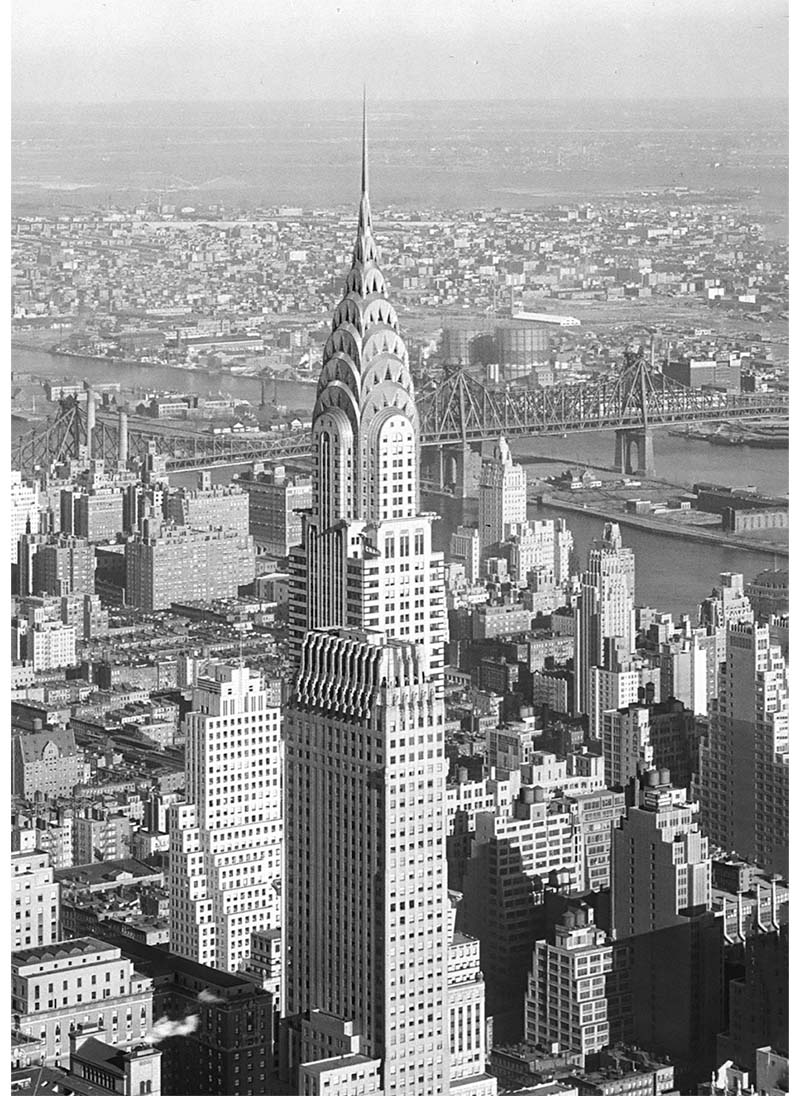

Photomontage: • Captain Roy Keeler’s log book cover & July 1933 flights (PAHF Collection). • Watercolor sketch of Mt. Pelée, Martinique, by the author of the book “To the River Plate and Back,“ by W. J. Holland (Putnam’s Sons, 1913), p. 435. (Biodiversity Heritage Library https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/3510733#page/1/mode/1up)

Sitting atop the Atlantic and Caribbean tectonic plates’ conjunction, Martinique’s, Mount Pelée had spewed lava and ash for two years when Pan American Airways pilot, Roy Keeler radioed Miami on Friday, July 14, 1933 to inform Ed Critchley, Pan Am’s Caribbean Division Operations Manager, that he faced unexpected difficulties northbound from Cristobal, Canal Zone, to Miami.

The message read:

"SHIP HAS BEEN ACCUMULATING DUST FROM CRISTOBAL TO CIENFUEGOS. WIRES AND STRUTS LOOK AS THOUGH SHIP HAS BEEN TAXIING ON A DIRT ROAD"

According to Pan American Air Ways, “When the ship pulled into Miami, Pilot Keeler's statement was fully justified.” The grimy aircraft looked nothing like the pristine Commodore Keeler commanded on his Wednesday, July 5 Miami exit.

Keeler speculated that the dust that he had flown through for two days was volcanic and Martinique’s Mt. Pelée was the logical source. Although no point on the Cristobal to Barranquilla to Kingston to Cienfuegos to Miami was closer than 1,000 miles from Martinique, Mt. Pelee was the region’s only erupting volcano.

After consulting system-wide meteorological reports, Keeler and Critchley agreed that a tropical storm forming near St. Kits in the Leeward Islands must have pushed the dust west into the central Caribbean Sea and into Keeler’s flight path.

Regardless of the dust’s source and propellant, Pan Am’s Consolidated Commodore NC670M needed a bath, followed by a through inspection to ensure that any problems with this “dirty bird” were merely cosmetic.

Source: “Pan American Air Ways,” Vol. 4., No. 4., July 1933, p.18.

July 19, 1933

“PAA’s Andes Aerial Aerie”

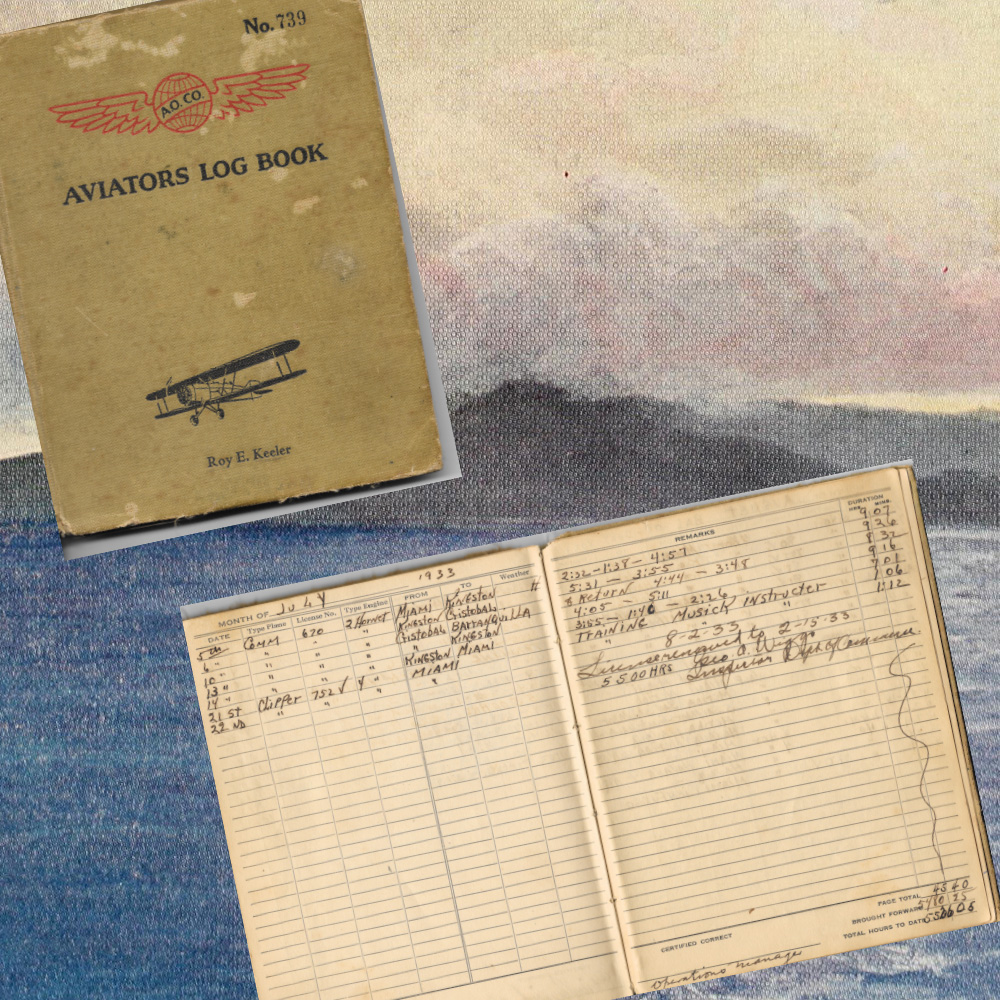

Photo: “Pan American Air Ways,” Vol 4., No. 4, July-August 1933, p.18 (PAHF Collection).

Mr. Nemzoff, Radio Operator in the Pan American/Grace Airways (PANAGRA) system, broadcast from the top of the world starting in July 1933 when, at 12,500-foot altitude, he tapped the telegraph key from inside a small hut dubbed “La Cumbre weather reporting station.” Reporting on this new station, “Pan American Air Ways” (Vol. 4. No. 4, July-August 1933, p. 18) claimed that the hut’s (cum, transmission station) altitude gave it bragging rights as the “highest of its kind in the world.”

Nemzoff’s job was to report weather conditions in an attempt to make the Santiago, Chile to Buenos Aires route safer, particularly the 150-miles between Santiago and Mendoza, Argentina which threaded the Uspallata Pass situated between Mount Aconcagua (21,555 ft.) and Mount Tupungato (21,560 ft.). Weather in this part of the Andes was unpredictable and pilots often found themselves flying into snow, ice, and high-altitude storms with hurricane-strength winds that neither the PANAGRA bases in Chile or Argentina were aware of. While these pilots were trained to “fly blind” using instruments, doing so in the tight confines of the Uspallata Pass pushed the envelope of Pan Am’s “Safety First” operational guidelines.

Mr. Nemzoff was using new radio sets developed by Pan Am’s Communications Department at the 36th Street Airport maintenance complex for use in extreme climates. These “cold” sets’ first deployments were to Alaska in support of Pan Am subsidiary, Pacific Alaska Airlines, and then to the Andes mountains in support of PANAGRA.

Source: “Pan American Air Ways,” Vol 4., No. 4, July-August 1933, p.18 (PAHF Collection).

July 26, 1933

“4 Horses: 1 draft-horse; 3 thoroughbreds”

Photomontage: Left: Panagra Ford Tri-motor; Right: Pacific Alaska Consolidated Fleetster; Bottom: Pacific Alaska Consolidated Fleetsters with Skis (Pan Am Historical Foundation Collection).

Pan American Airways was buying aircraft in mid 1933 to meet service demands across the growing system. Four purchases grew Pan Am’s “stable” by three thoroughbreds and one draft-horse. Three, new and fast, airplanes reflected commercial aviation’s leading technology; the fourth, proven, old, and slow, did not.

Following Eastern Airline’s takeover of New York-based Ludington Airlines in early 1933, Pan Am bought three of its barely used Ludington Consolidated Fleetster 17-AFs (N703Y, N704Y, N705Y) for Pacific Alaska Airways. These nine-passenger, high-wing monocoupes cruised at 150 miles per hour and were efficient and flexible: they could be fitted with wheels or skis; they could shift from passenger to freight configurations in under two hours.

The three arrived in Miami for overhaul and modification to prepare for Arctic flying conditions, including installing PAA-designed cold-hardened radios. One novel modification allowed the engine cowling to be shut completely to enable more efficient engine warmup in arctic cold. Additionally, the standard instrument panel was replaced by a Pan Am design to allow for “blind” flying and that also included four temperature gauges to monitor ambient temperature, carburetor temperature, oil temperature, and cylinder-head temperature.

The Fleetsters were in service by the end of October but their Alaska time was limited. N705Y soon crashed and was written off, and N703Y & N704Y were sold to Russian trading organization AMTORG (Amerikanskaya Torgovlya) in 1934.

The fourth aircraft delivered in June signaled the beginning-of-the-end for a storied bird. Ford Tri-Motor 5-AT-D (NC9659) was the last “Tin Goose” to roll out of Ford’s Michigan factory on June 7, 1933. It was delivered to Pan Am’s Western Division’s Brownsville, Texas base later that month then flew south to serve Pan American/Grace (PANAGRA) in South America before ending its career sporting China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) livery in China.

Sources:

• Bond, W. Langhorne, “Wings for an Embattled China” Lehigh University Press, 2001.

• Davies, R.E.G. “Pan Am: an airline and its aircraft” Orion Books, 1987.

• “Pan American Air Ways,” Vol. 4, No. 5, October 1933, p. 6 (Pan Am Historical Foundation and University of Miami Special Collections).