JUNE 1933

JUNE 12, 1933

“Aerial Hitchhikers”

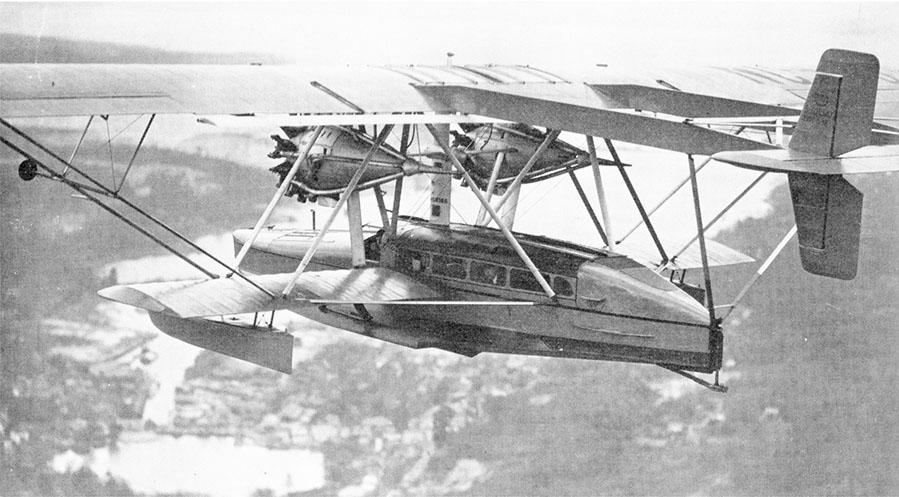

Photomontage: Monocoupes & Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 (Caribbean Clipper).

Photomontage: Monocoupes & Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 (Caribbean Clipper).

Clockwise: Monocoupe Model 70, designed by Ken Luscombe, made by Central States Aero Corp., introduced 1928 -now at Hiller Aviation Museum, San Carlos, California. Photo by Diderot, May 2015. ( Wikimedia, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain). / Monocoupe 110 ‘NC18629’ c/n 6W-00. Built 1931.On display at the Oakland Aviation Museum, Oakland, CA. Photographer Alan Wilson, UK, taken 5th March 2016. (Wikimedia, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license). /Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 Caribbean Clipper (PAHF Collection).

Kingston, Jamaica’s "Daily Gleaner" drew June 12, 1933 readers’ attention to a “first”: Mr. Ernesto J. Samper and Mr. C.B. “Scottie” Burmood would attempt “the Kingston to Colombia crossing by a land plane.”

Pan American Airways had flown this 500-mile route since May 1930 using multi-engine flying boats (Consolidated Commodores and Sikorsky S-40s) outfitted with custom radio systems. No land-based aircraft had attempted the jump, and few pilots would consider doing so in two-seat single-engine airplane with one fuel tank and no radio; still Ernesto and Scottie were taking 2 of 6 trainers he had purchased in Moline, Illinois to Ernesto’s Colombia Civil Aviation College in Bogota.

A Daily Gleaner reporter described the two Monocoupes as “extremely capable and good looking machines, built purely for economic solo flying” but omitted the aircraft’s 500-mile range and lack of radios. On the 500 mile Kingston/Barranquilla run these pilots had no room for navigational error. With that one-shot reality, the two chose caution over daredevilry and arranged to trail Captain R.O.D. Sullivan’s Caribbean Clipper (NC81V) Monday morning Caribbean crossing.

As the huge four-engine Sikorsky lifted off of Kingston Harbor at 6:30 a.m., Samper and Burmood, in their fly-speck Monocoupes, left nearby Up Park Camp and began an aerial hitchhike relying on the Pan Am crew’s experience, navigation skills and radio-direction system…and, of course, the ability to pluck either man out of the Caribbean should he have to ditch his aircraft along the way.

Three months later Scottie Burmood returned in another Bogota-bound Monocoupe and again waited until Monday morning, August 21, before attempting the crossing. This time he trailed the American Clipper (NC80V) and gave Chief Pilot, Ed Musick’s one southbound passenger something to watch other than clouds and waves during the four-and-one-half hour flight.

• Author’s database

JUNE 14, 1933

“PAA Embraces Art Deco”

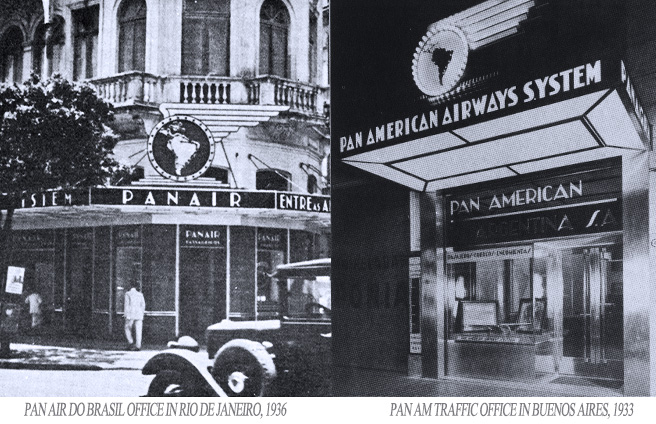

Photo, left: Buenos Aires Traffic Office, 1933:"Pan Am Air Ways," Vol. 4, No. 3, June 1933, p. 19. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41043/rec/3

Photo, left: Buenos Aires Traffic Office, 1933:"Pan Am Air Ways," Vol. 4, No. 3, June 1933, p. 19. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41043/rec/3

Pan American Airways, Inc.’s public façade signaled a “modern” enterprise — from the company’s New York City headquarters in the Chanin Building (122 East 42nd St.) and its next home in the Chrysler Building (405 Lexington Ave., catty-corner to the Chanin Bldg.) — to its just renovated Buenos Aires, Argentina office — Pan Am’s corporate 1933 look was Art Deco.

Pan American Air Ways June 1933 issue trumpeted that new and refurbished facilities throughout North and South America were:

“Thoroughly in keeping with the modern trend, yet avoiding extremes … the new scheme of decoration combines simplicity with beauty.” The design goal was specific: “Within a comparatively short space of time … all … offices will be decorated in this typical pattern so that in each city the Pan American headquarters will be readily identified at a glance.”

Buenos Aires’ remodeled Art Deco office boasted “A marquee over the entrance [that] bears the Pan American name and insignia done in lights … showing the outline of the entire system on a large map of South America. Within, the long counter, done in black, bears the insignia of the system on each panel.” Every South America and Caribbean Pan Am office underwent a similar makeover; Sao Paulo’s renovated space was deemed “one of the most attractive business establishments in the city.”

This visual branding was alive in North America, too, in Pan Am’s “Grand Central Station of the air,” Dinner Key marine terminal under construction in Miami, Florida. Designed by William Delano and Chester Aldrich, the terminal wowed crowds at its 1934 opening and along with the Chanin and Chrysler Buildings is listed on the National Historic Registry for Art Deco in United States’ architecture.

Source:

• "Pan Am Air Ways," Vol. 4, No. 3, June 1933, p. 19. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41043/rec/3. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41043/rec/3

JUNE 21, 1933

"Staffing for CNAC"

Photo: Sikorsky S-38 in Flight (PAHF Collection).

JUNE 25, 1933

"Assessing the North Atlantic"

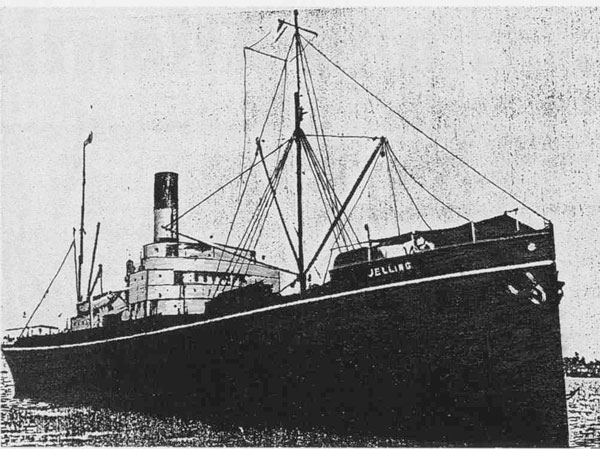

The SS Jelling, 1933 still photo, courtesy of R.E.G. Davies

Pan American Airways’ Miami-based employees Harold Horman and William Jarboe answered “Greenland” when asked, “What did you do over the summer?” For ten weeks the two men sailed aboard the Pan Am-chartered Danish ship, SS Jelling, rather than their usual duty stations aboard Pan Am aircraft. The ship set sail from Philadelphia in late June 1933.

This Pan Am expedition (one of several sponsored by Pan Am to explore the northern transatlantic route) was under command of aviator Robert Logan who had worked for Pan Am in South America. The expedition conducted research on weather conditions, mapped potential airport locations, measured ocean depths and currents, and looked for likely harbors for flying boats. It also served as the depot ship supporting the Lindberghs when they surveyed Greenland at the beginning of their long exploratory flight around the Atlantic.

A Fall update in “Pan American Airways” highlighted the two Pan Am employees:

“Flight Mechanic H. H. Homan and Radio Operator Jarboe are again on duty at Miami, following their ten weeks' duty on the steamship JELLING, northern survey base ship for the past season's field work in the Far North. Mr. Homan was interviewed over radio station WIOD in Miami concerning this expedition, on one of the regular programs presented by the Public Relations department.”

• Jelling Expedition; Homan & Jarboe assigned 10 weeks (“Pan American Air Ways,” Vol. 4., No.5, Oct. 1933, p.26): University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways Inc., records. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41167/rec/5

JUNE 28, 1933

"Landing on the Roof"

Circa 1930s Airport construction at Tegulcigalpa, Honduras (PAHF Collection).

Contemporary runway construction is a science. Building a landing surface in 1933 was equal parts science, alchemy, and luck.

Pan American Airway’s first airport engineers understood that runways require level ground, yet flat land is inherently dangerous because it is formed by water and, “When it is wet, it is soft.” And, when wet, results in mud --- “126 different types of mud.”

“Pan American Air Ways” (June 1933), the company’s in-house magazine, explained the challenges the engineering department faced in locating, constructing and maintaining landing fields to meet the company’s “Safety First” mandate. Pan Am’s early fields were miracles of perseverance as much as design: Key West’s landing strip swallowed “400 truckloads of rock … before a solid surface could be attained”; “at Merida [Yucatan, Mexico] … a steamroller chugged merrily along a runway under construction” then “disappeared”; an engineer demonstrated PAA’s 36th Street International Airport’s instability by taking a shovel and “almost without effort pushed the long handle into the ‘flat piece of ground’” inches from the runway’s edge “until the entire shovel disappeared.”

The metaphor, “The airport is a roof,” guided construction protocols to allow Pan Am’s land-based aircraft to land on that “roof” without it caving in, noting that the “steamroller weighing five or six tons” is nothing compared “to a Ford Trimotor which, landing, may have an effect approximating that of a load of 20 tons!”

One engineer described the runway build: “The … first concern is to seed (the) port with quick-growing, heavy-rooted grasses. The fine network of roots binds the surface together. When this is wet enough, crushed stone or gravel is added and rolled down into the surface while wet.” An important caveat, however: “The idea is not to make a pavement. Indeed, care is given not to apply too much stone, as it is desirable to have grass growing amid the stone.”

Source:

• “At the Ends of the Airways.” “Pan American Air Ways,” Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 9-11 (PAHF Collection).