Lessons Learned, the 1927 Dole Race

From the Berkeley Daily Gazette, August 15, 1927

The Challenge

When Pan American Airways announced that the company was ready to begin regular service across the Pacific, there was a great deal of skepticism about the plan's wisdom. Dr. George Lewis, Director of the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics - NACA (forerunner to NASA) - personally offered to provide public relations cover if Juan Trippe wanted to back out of the plan. Two of Pan Am's company directors quit rather than be associated with what might turn out to be a debacle. These people remembered an event eight years earlier that still haunted aviation in 1935.

It was August 16th, 1927, only 86 days since Lindbergh had single-handedly fired the world's imagination with his stunning solo flight from New York to Paris. On the field at Oakland California's municipal airport next to San Francisco Bay, a bevy of would be "Pacific Lindberghs" readied their aircraft for a flight to Hawaii.

They were ready to compete for a $25,000 prize for the winner (and $10,000 for the runner-up) to risk a flight of over 2,400 miles, entirely over water.

The spark for the challenge came just two days after Lindbergh arrived in Paris. Two Honolulu newspaper reporters sent Hawaiian pineapple magnate James Dole a telegram, which read in part: This moment ripe for someone offer suitable prize non-stop flight Hawaii.

Dole, pictured here wearing a suit and hat at the finish of the race, took the bait, and shortly thereafter announced his offer to the world. He hoped that Lindbergh himself would accept the challenge, but he declined. There were other takers though. The rules for the contest stated that the event would be overseen by a rules committee, and was slated for an August start.

Dole, pictured here wearing a suit and hat at the finish of the race, took the bait, and shortly thereafter announced his offer to the world. He hoped that Lindbergh himself would accept the challenge, but he declined. There were other takers though. The rules for the contest stated that the event would be overseen by a rules committee, and was slated for an August start.

The Dole Race proved to be a tragic and ironic epilogue, as far as aviation history is concerned. Dole's hope was that a stunning, well-publicized, never-before-accomplished flight from the mainland U.S.A. to far-distant Hawaii (especially one associated with his name) would stimulate the commercial development of an aerial route that would dependably serve the islands. That did transpire, but not because of Dole's prize.

The Contestants

As it happened, the Dole Race contestants would all prove to be significant for their own reason. In late June, an Army Air Corps Fokker C-2 Tri-Motor (a military version of the Fokker F. VIIa) arrived in California, ready to fly to Hawaii. Army Lieutenants Albert Heggenberger and Lester Maitland had convinced their boss Army Air Corps Chief Maj. General Mason Patrick that a flight to Hawaii could be made safely. It would be proof of years of carefully conducted advances in aircraft operational and navigational techniques that the Army had been conducting, they argued. General Patrick said proceed - but there would be no public announcement.

When the Army pilots landed in Oakland after a long shake-down flight across the country, they encountered civilian airmail pilot Ernie Smith, primed and ready to try the same flight. He had decided to forgo a possible Dole prize win in favor of the glory of being first across to Hawaii. When the big Army Fokker - now named the "Bird of Paradise" - lifted-off for Hawaii on the morning of June 28th, Smith was ready to go two hours later. Unfortunately (or not, as it turned out), the plane's navigator's windshield blew off shortly into the flight. Charles Carter, Smith's navigator insisted they turn around and land. When they did, Carter declined to re-board. Smith was bitterly disappointed, but when he did finally leave for Hawaii on July 14th, he did so with a much more competent navigator named Emory Bronte on board, as well as improved navigation gear and a radio.

The "Bird of Paradise" safely made Honolulu in just under 26 hours, despite some anxious moments due to carburetor icing and failed radio and navigational aids. Smith and Bronte, following in July, made it too - just. Their single-engine Travel Air monoplane "City of Oakland" ran out of gas over Molokai, 50 miles shy of Honolulu. Smith managed to bring the plane down in a clump of trees, but both he and Bronte walked away unhurt to a heroes' welcome - the first civilians to fly to Hawaii. The Army flight in particular proved that careful preparation combined with proper training and adequate equipment was the way forward to real progress in aviation. Smith and Bronte's flight seemed to prove that luck was still a substantial factor in transoceanic aviation, but that it was possible. For a brief moment, the challenge of the long flight across the Pacific seemed to shrink in significance, but that moment would prove to be short-lived.

Back in Oakland, the Dole Race participants had lost their chance to be first across to Hawaii. Now it was down to a race for the money, and that $25,000 (perhaps worth $300,000 today) was a powerful motivator. And it was still great press. Lindbergh's flight had ignited a firestorm of interest in aviation, and the group of aviators that were preparing to reach across the wide Pacific made great copy. Flying across all that open water, aiming for a few bits of land was not a job for the faint-hearted or the ill-prepared. As one contestant put it succinctly: "There are but two goals. The Hawaiian Islands or the bottom of the Pacific."

Fifteen entrants ponied up the $100 entrance fee.

To be fair to Dole, he wanted the event to be overseen by responsible professionals who would understand the risks, and enlisted the National Aeronautical Association (N.A.A.) the American affiliate of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, the internationally-recognized governing body for all aviation competition, to oversee the event. The N.A.A.'s committee included Maj. Clarence M. Young, head of the Enforcement Division of the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce. (Young would become Pan American Airway's Chief of the Pacific Division when Pan Am took on the challenge to fly the Pacific in 1935.)

To be fair to Dole, he wanted the event to be overseen by responsible professionals who would understand the risks, and enlisted the National Aeronautical Association (N.A.A.) the American affiliate of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, the internationally-recognized governing body for all aviation competition, to oversee the event. The N.A.A.'s committee included Maj. Clarence M. Young, head of the Enforcement Division of the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce. (Young would become Pan American Airway's Chief of the Pacific Division when Pan Am took on the challenge to fly the Pacific in 1935.)

Young set what seemed like sufficiently stringent rules to weed out the unqualified. He appointed a team to inspect the aircraft, vet the navigational skills of the crews, and ensure that the planes were capable of flying the 2,400-mile range with adequate fuel with at least a 15% safety margin.

Even before the Dole Derby (as it became known) began, the event was shrouded in tragedy. On August 8th George Covell and R.S. Waggener died during a flight to Oakland from San Diego, when they flew their "Spirit of John Rodgers" into a fog bank - and the cliff it hid - on the California coast. The very next day another Dole contestant British pilot Arthur Rogers died bailing out of his aircraft, "Angel of Los Angeles" during a test flight before ever reaching Oakland.

Another aircraft, "Pride of Los Angeles" overshot the runway while attempting to land at Oakland and came to grief on the mudflats of San Francisco Bay on August 11th, but the three crew members managed to escape unhurt.

By the day before the race, three other contestants had failed to arrive or abandoned the effort. On the very day of race, one more entrant - "Miss Peoria" was disqualified when the plane was judged to likely run out of fuel long before reaching Hawaii. The owner was furious, but the two men recruited to do the actual flight were reported to be much relieved.

By the 16th of August, the surviving entrants numbered eight aircraft, a motley group of aviators - and one passenger.

Four of the entries were flown by men with military flying experience. There was the dashing former Army Air Service flier turned-stockbroker Jack Frost, with his navigator Gordon Scott, flying the very first Lockheed Vega, christened "Golden Eagle." (Frost was backed by none other than William Randolph Hearst and his "San Francisco Examiner" newspaper.) The "Pabco Pacific Flyer" was unique, in that veteran Lafayette Escadrille flier (and Oakland native) Livingston Irving would be flying solo. "Dallas Spirit" was piloted by another World War veteran pilot, Bill Erwin with navigator Alvin Eichwaldt. "El Encanto" was flown by Englishman Norman Goddard, a Royal Flying Corps veteran, along with his navigator Ken Hawkins.

The "Aloha" was the sole Hawaiian entry, flown by Martin Jensen and navigator Capt. Paul Schluter. "Oklahoma," a Travel Air like the ship flown by Ernie Smith to Molokai the month before, was flown by Bennett Griffin and navigator Al Henley. One other Travel Air, the "Woolaroc," was also ready to go that morning, flown by Art Goebel and navigator Bill Davis.

But far and away, the most attention was granted to the "Miss Doran." The plane was so named because her nominal "captain" was a passenger named Mildred Doran, a 22 year-old Flint Michigan schoolteacher. Her pilot was Auggy Pedlar, the navigator Vilas Knope. Newspapers had a field day with the story of the brave young woman risking her life.

The Start of the Race

The actual start of the race was a media frenzy, with newsreel camera crews, photographers, race officials, and contestants' support crews running around in front of a crowd estimated at well over 50,000. The runway was roped off, but onlookers pressed in, held back by police and U.S. Marines.

At 11 a.m., the race began. "Oklahoma" was first off, and was airborne with half the runway left. "El Encanto" was next, and staggering into the air under the fuel load she carried, dipped a wing and ground looped, coming to rest in a jumble of smashed wing and dust (photo, left). The "Pabco Pacific Flyer" was next up, but didn't get airborne, and was towed back to the starting line.

"Golden Eagle" was soon off the line, already flying at 200 ft. at the airport boundary, a seeming perfect start. The Lockheed Vega was equipped with the latest instruments and carried safety gear that could keep her afloat for a month, it was said.

"Miss Doran" got off too, using almost the whole runway to do it. Mildred Doran was seen waving out of the window as the plane gathered speed. The bright yellow "Aloha" was soon gone too, just clearing the rooftops of San Francisco on its way west. That left "Woolaroc" and "Dallas Spirit" which both took off without incident.

The "Pabco Pacific Flyer" remained on the ground, its crew feverishly working to repair the tail skid which had broken during the first takeoff attempt. The crowd was waiting quietly for the "Flyer" to be rolled back to the starting line, when suddenly three aircraft arrived back overhead. The "Oklahoma" and "Miss Doran" were having serious engine trouble. "Dallas Spirit's" fuselage fabric was ripping off and peeling back in flight. It quickly turned out that "Oklahoma's" engine was fried, and out of the race, as was "Dallas Spirit".

By now, the "Pabco Flyer" was repaired, and ready to try again. Like before, the attempt was a failure, only this time the result was a racked-up aircraft, but the crew walked away unhurt (photo, right)

Pilot Auggy Pedlar on the right with Passenger Mildred Doran

The focus was now all on "Miss Doran," whose mechanics were working feverishly to change out the spark plugs. While this was going on, Mildred Doran was caught in a terrible moment of indecision, and in tears. The crowd yelled to her to stay behind, and navigator Vilas Knope tried to convince her to stay as well. For all her obvious misgivings, Mildred Doran decided to take the risk, and when the plane was pronounced fit to fly again, she got onboard. "Miss Doran" was soon winging its way out over the Pacific, the last to leave and hours behind the other aircraft.

The drama was over, the crowd went home. The waiting began.

Winners

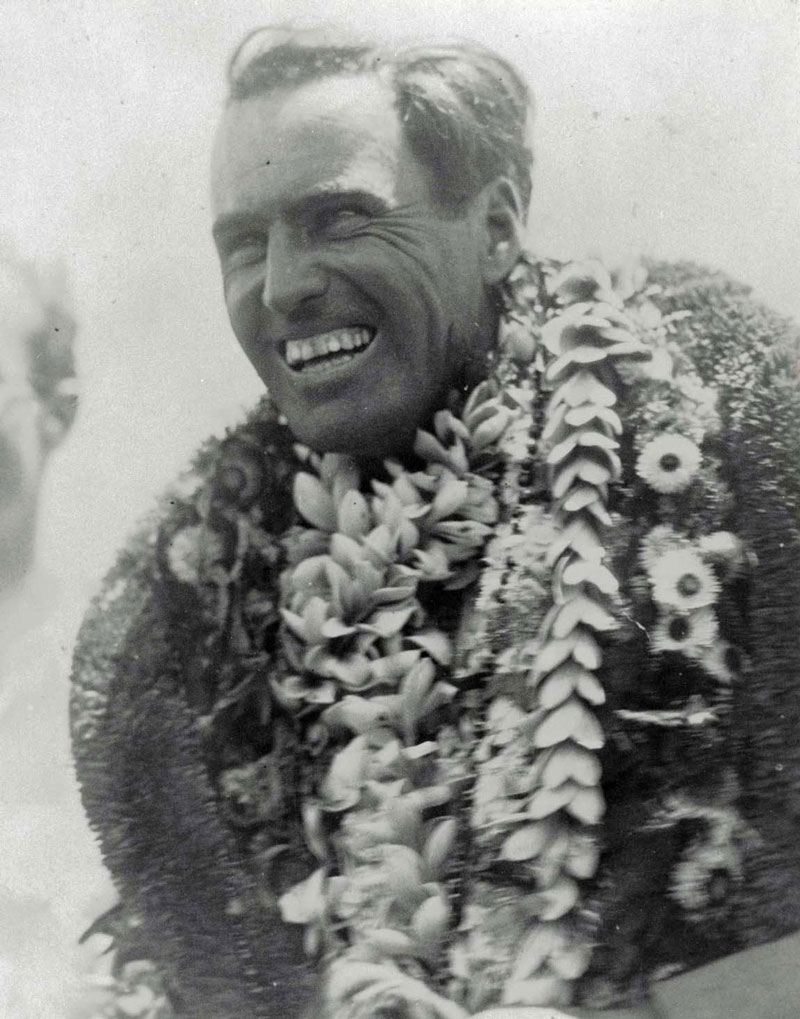

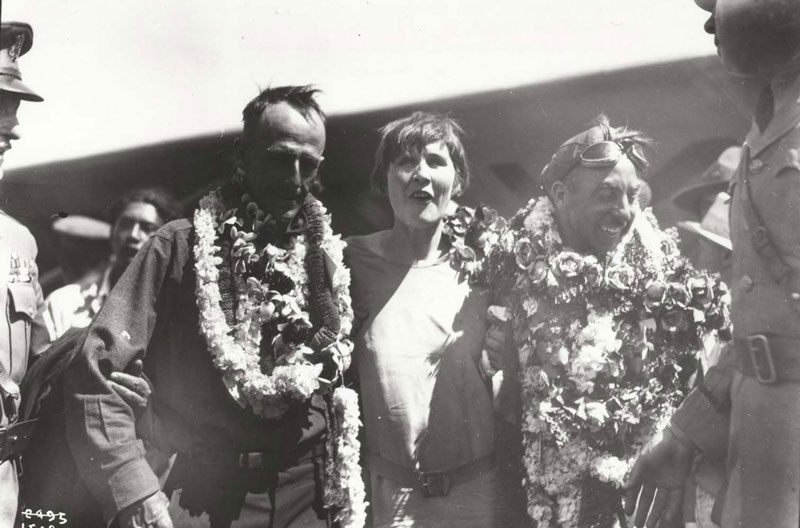

Photo: Goebel after winning the race. Photo: Jensen (r) and his wife, Marguerite, and navigator Paul Schuler. Photo: The winning planes: Woolaroc and Aloha.

The next day, August 17, at Honolulu's Wheeler Field an excited crowd had gathered to greet what was hoped would be the entire group of planes that had made it into the air at Oakland. The first to arrive was "Woolaroc." Art Goebel and Bill Davis were tired but triumphant. The navigation was spot on, and the piloting proved critical, as former stunt man Goebel was able to recover from several "graveyard spins" caused during the complete loss of visual reference (and lack of adequate instruments to stay oriented). Three hours later, the "Aloha" arrived with Jensen and Schluter. Their trip was hair-raising, due to navigational inadequacies that almost cost them their lives. They landed with only 4 gallons of fuel left.

The Others

The Others

But as for the others - "Golden Eagle" and "Miss Doran" - nothing was ever heard from them again. The loss of those five lives would soon be compounded further. A massive search was soon organized, with Army and Navy joining in. Martin Jensen climbed back into the "Aloha" to search near Hawaii. An Army search plane went down, taking the lives of its two crew members. Back at Oakland, Bill Erwin and Alvin Eichwaldt set off in their now-repaired "Dallas Spirit" to search, but they never returned either. The death toll from the Dole Derby would end up totaling 12 lives. Sober contemplation of the cost would bring into question the wisdom of trying to bridge the oceans by air.

The Turning Point - November 1935

In the final analysis, the Dole Race proved that transoceanic flight was a serious job, requiring practical preparation, real skill, adequate training, equipment equal to the task, and not least, respect for the ocean and all its challenges.

And it was not too long before others took up the transoceanic challenge. The very next year, Australia's Charles Kingsford-Smith took off from that same Oakland airport in a Fokker Tri-motor, and flew all the way back to Australia with stops in Hawaii and Fiji. Seven years after that, a mass flight of U.S. Navy patrol planes made the trip.

But the real turning point came in November 1935. Armed with the collective experience of those who came before, as well as their own experience in mastering over-ocean distances, Pan American Airways finally answered the question as to whether it was time to fly the Pacific as a regular proposition. This year will mark the eightieth anniversary since then, and we've never looked back.

Sources:

"Dole race, 1927. With noted aviators and pilots, including Emory Bronte, Ernie Smith, Hegenberger, Maitland, Arthur Goebel and Lieutenant William Davis, Martin Jensen, Captain Paul Schulter, Major Livingston Irving, Norman Goddard, Kenneth Hawkins, Bennet Friffin, Al Henley, Lieutenant Knope, Miss Mildred Doran and Auggie Pedlar, Gordon Scott and Jack Frost, Captain Bill Erwin and Navigator Alvin Eichwaldt. Scenes include airplanes taking off, a demonstration of a life raft, the crash of the Pabco Flyer and El Encanto."

https://archive.org/details/DoleAirR1927

Read more about Mildred Doran at Air and Space Magazine: Above and Beyond, Aunt Mildred.

http://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/above-and-beyond-aunt-mildred-79371463/?all