Loading the China Clipper: A personal recollection

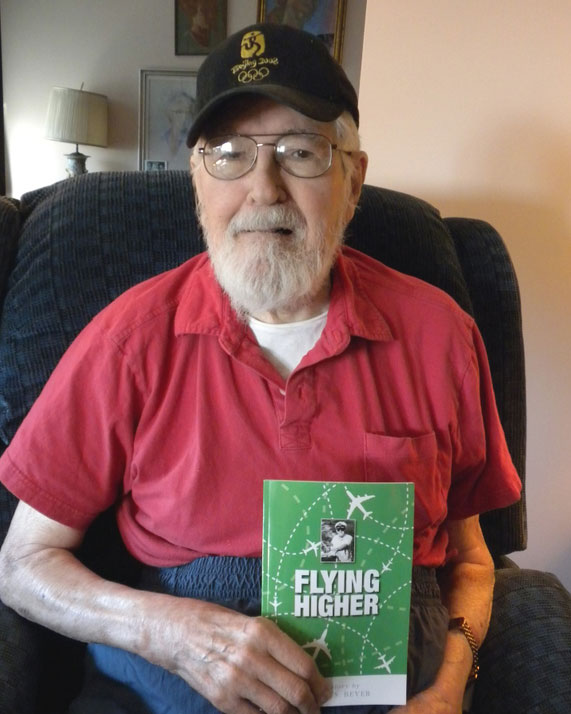

Excerpted from Flying Higher by Morten S. Beyer

(Trafford Publishing, 2010)

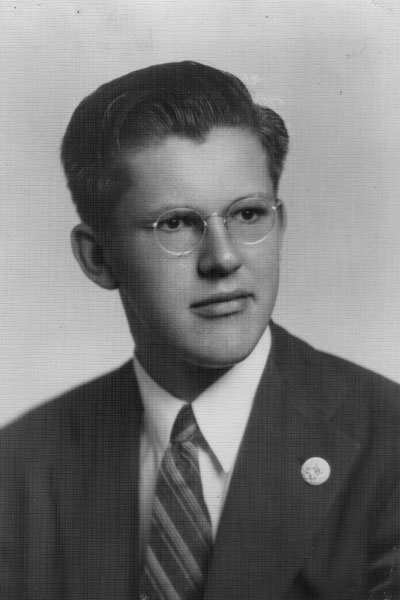

In late 1943, the by-then venerable Martin M-130 flying boat was transferred to Miami to begin operations in Pan Am’s Eastern Division. A young operations employee named Morten Beyer was tasked with the job of figuring out how to radically expedite the critical wartime operation of loading and unloading the plane, which had been taking many hours. This recounting was adapted from Mr. Beyer’s exciting autobiography, Flying Higher, and presented here courtesy of the Beyer Family Archive. Photo: Morten Beyer in 1943.

In late 1943, the by-then venerable Martin M-130 flying boat was transferred to Miami to begin operations in Pan Am’s Eastern Division. A young operations employee named Morten Beyer was tasked with the job of figuring out how to radically expedite the critical wartime operation of loading and unloading the plane, which had been taking many hours. This recounting was adapted from Mr. Beyer’s exciting autobiography, Flying Higher, and presented here courtesy of the Beyer Family Archive. Photo: Morten Beyer in 1943.

We did not know quite what to do with our new long-range plane. The ultimate plan was to open a new route to Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo via the Caribbean, South America and West Africa, but this was delayed by German submarine activity threatening our bases. We finally elected to put the M-130 on a six-day a week run from Miami to Cristóbal on the northern coast of Panama, an eight hour nonstop flight each way. The plane was scheduled to depart Miami at midnight, arrive in Cristóbal at dawn, make a quick turnaround for unloading, reloading and fueling, and then return to Miami by late afternoon.

But getting the aircraft loaded and out of Miami proved to be a daunting task and every flight ran six to eight hours late because the ground crews could not get the plane loaded. Numerous flights were canceled due to these delays and backlogs of priority passengers and cargo built up (it was wartime and everything traveled priority). Operations Manager Jimmy Walker assigned me to fix the problem.

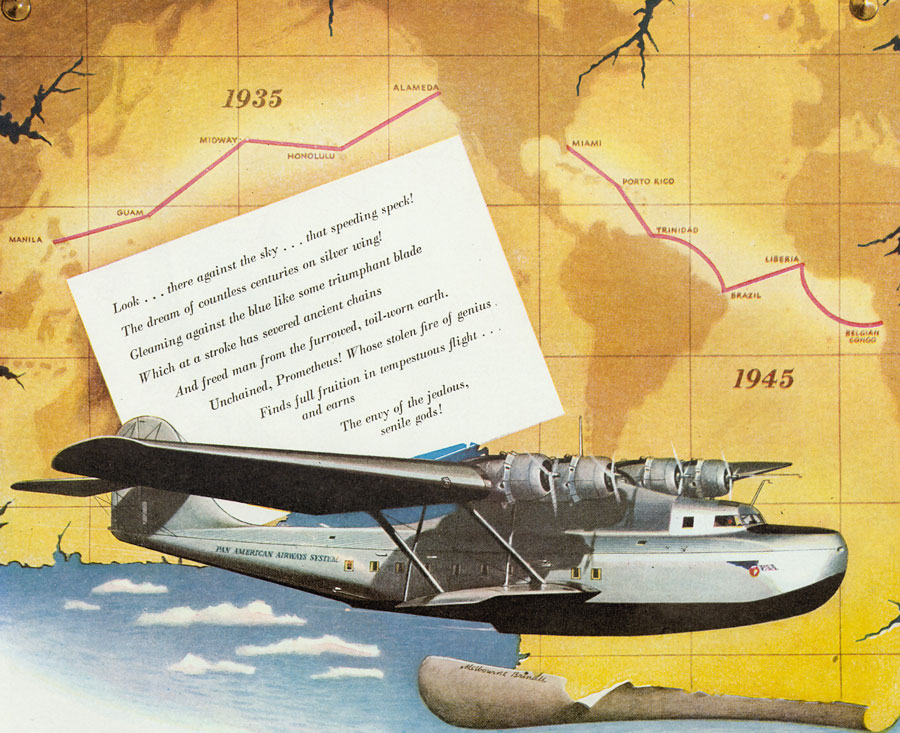

Fortune Magazine image, April 1936

That night I went to the Dinner Key Marine Terminal (now the Dade County, Florida executive building) to size up the situation. The China Clipper was moored at the far end of one of the piers at which we docked our seaplanes because it was too big to fit at the close-in docks. A long narrow walkway led from the terminal area to the aircraft. Entrance to the aircraft was through a single hatch on the top of the aft fuselage through which the passengers entered and left, the crew boarded, and the cargo and passenger supplies were loaded and unloaded. The aircraft had an exit over the sea wings amidships, but this could not be used given the docking arrangements in Miami. A great deal of the aircraft’s load was high priority cargo – as many as fifty to a hundred pieces a night, plus baggage and mail sacks. The rear entry hatch was the bottleneck. We had a crew of 30-odd loaders who carried boxes, cartons, mail sacks, pieces of baggage, catering boxes and everything else from the terminal out along the dock to the aircraft. They clambered up onto the top of the fuselage and made their way down the stairs into the rear cabin. There they shuffled their way forward, through five bulkhead doors, until they at last reached the cargo compartment, deposited their loads, and then made their way back against the oncoming loaders until they at last reached the dock and terminal. The result was, of course, chaos and delay. It took six hours to load the aircraft in this fashion.

In Cristóbal, Panama, there was no such problem. The aircraft moored next to a large floating barge. The passengers entered and exited through the rear exit and the cargo was handed out through the sea wing exit and piled directly onto the barge. Passengers and cargo were transferred to shore by lighters, and the entire loading and boarding process took about an hour. But wartime security regulations and the FAA (then CAA) made such practical solutions impossible in Miami. Another solution had to be found.

In Cristóbal, Panama, there was no such problem. The aircraft moored next to a large floating barge. The passengers entered and exited through the rear exit and the cargo was handed out through the sea wing exit and piled directly onto the barge. Passengers and cargo were transferred to shore by lighters, and the entire loading and boarding process took about an hour. But wartime security regulations and the FAA (then CAA) made such practical solutions impossible in Miami. Another solution had to be found.

Photo left: A Tribute to Martin M-130 in a Martin Aircraft Company Ad

After an hour of watching the chaos and confusion as the loaders struggled to carry their cargo to the hold and return for more, I positioned myself at the top of the cabin entry stairs. Six loaders were assigned below to pass the cargo, human chain fashion, from one compartment forward to the next when I handed it down. The rest of the loaders were positioned as a human chain along the dock, passing the boxes, bags and sacks from one to the other rather than carrying them individually. Things began to move. I yelled at the topside loaders to move it along faster, and sped up the below-decks loaders by passing the cargo down to them even faster and faster. Within 30 minutes we had the China Clipper loaded and the cargo tied down. We were already delayed from the previous night’s operation and from the time lost before we set up our human chain. But we got within two hours of the scheduled takeoff time, and the return flight was also about two hours late.

The next night I was there again as the China Clipper taxied in across Biscayne Bay, the four engines sending great plumes of white spray against the darkening sky. She was moored at the dock and I again pressed my human chain into service, unloading her in twenty minutes (northbound cargo loads were light – mostly baggage and mail). The maintenance crews now had a couple of hours to clear the snags, check the engines and prepare for the next flight. Two hours before departure I called the loading crew together and advised them that we were going to handle the loading the same as last night, and that I expected an on time departure. We chose up the below decks crew and the dock crew and walked out to start loading. We were finished in less than an hour and made a timely departure. In the months that followed, the China Clipper completed six round trips a week between Miami and Panama with seldom a delay or mechanical interruption. Utilization was an unheard of 400 hours per month, 16 hours a day, 25 trips a month. After almost a year we were ready to launch the Leopoldville, Congo service and the Panama flights were taken over by our three Boeing B-307s.

Another view of a Clipper's loading stairs. North Haven expedition member Bert Voortmeyer stands next to the Philippine Clipper. Photo by Capt. W.B. Voortmeyer, courtesy Carol Nickisher.

The key to making the China Clipper loading work was not only to set up the human chain, but also to station myself in the key position at the top of the hatch and use my position to urge the two groups of loaders, neither of whom could see the other, to move faster. Not wanting to be outdone by the other group, each did.