AUGUST 1933

Scroll down to read

Five August 1933 posts

August 2, 1933

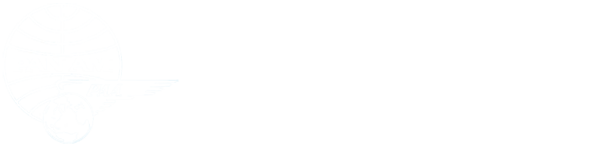

“Hanger B’s Proud Papas”

Photomontage: Miami’s 36th Street Airport, Fokker F-10 and Maintenance crews c. 1930s (PAHF Collection).

It’s the hard-core aviation family that names its kids Strut, Streamline, Backfire and Spark … and doing so leave the curious asking if other clan members are Prop, Rudder, Trim-Tab, or Altimeter. But, this was the case in early summer 1933 for the Splash quadruplets, residents of 36th St., Miami, Florida.

Although dad was a wanderer, the four newborns were awash in “uncles,” doting men who worked alongside “Mama” Splash at Pan American Airways’ maintenance facilities at the 36th Street Airport. These coworkers were eager to keep an eye on the babies while their mother continued to work (there was no paid maternity leave in 1933). From shop foreman to janitor, they volunteered to assist with childcare and serve as surrogate father figures because her contributions to the company mattered.

Mama Splash was an exterminator, an unglamorous, but essential job. Working alone in dark and hard-to-reach areas or under Hanger B’s high reaches, her daily inspection-and-interdiction routine kept Hangar B free of visitors particularly damaging to wood-and-fabric aircraft and electrical wiring sheathing. She was adept at rat removal, although she kept a watch out for moths -- winged pests with a taste for the expensive wool fabric that covered the seats in the company’s expensive aircraft.

Her job title: Hanger Cat.

Source:

“Hanger B Quadruplets Born” from "Pan American World Airways," Vol. 4. No. 4, July 1933, p. 5 (PAHF & Univerity of Miami Special Collections). https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/40881/rec/4

August 9, 1933

“Mrs. Archibald Goes to Washington”

Photo: B-314 at LaGuardia c. 1941 (PAHF Collection)

Pan American Airways, Inc. Executive Staff Memorandum No. 8 (August 23, 1933) announced the upgrade of its Washington, D.C. office to a permanent and fully staffed unit, effective September 1. Miami employee, Ann Elizabeth Monahan Archibald, knew of this development: she was traveling north to organize and manage the office. For twenty years, Mrs. Archibald, as she was always addressed, established herself as social/political powerhouse and company cornerstone.

Historians Marylin Bender and Selig Alstschul assessed her at the height of her sway as “the rotund widow of a Marine flier, (who) ran the office with the iron whim of a society dowager… Her technique was not to catch flies with honey, but to command government bureaucrats to do Pan American’s bidding.”

Harold Brock, PAA Pilot and later Director of the Atlantic Division, credits Mrs. Archibald as critical to Pan Am’s Africa 1941 start. Pilots fit for this difficult project were hard to find, until “Mrs. Archibald…got General (Hap) Arnold to release about 200 of his best Army pilots, 20 at a time, and (George) Kraigher picked out what he wanted.” General Arnold, and countless others knew what every new bureaucrat at the Civil Aeronautics Administration learned: “Mrs. Archibald will not take no for an answer.”

Described as “the doyenne of Pan American’s Washington office,” Ann cared deeply for service members regardless of rank and pulled any string to help them during World War II and she received 400 dolls from around the world as thanks. Equally appreciative of her wartime service, Portugal awarded her it’s highest civilian award, “The Most Ancient and Noble Order of Christ,” the first woman so honored, and decorated by the U.S. Navy for her World War II efforts, with its “Certificate of Merit.”

The first female executive in commercial aviation whom aviation historian, George Hopkins, names “a rarity at Pan Am ... [who] rose to become an essential Pan Am employee whose inside knowledge of government was indispensable to Trippe,” so much so that she was the only other person allowed to approve “must ride” designations for Atlantic crossings during 1941 and 1942. He notes, however, “Archibald was never promoted beyond the rank of assistant vice-president, despite the fact that she performed vice-presidential duties.” (p. 207)

Mrs. Archibald was at her desk and directing company dinners days before her death, January 17, 1953 and was buried two days later at Arlington National Cemetery alongside her husband, Marine aviator, Captain Robert James Archibald.

Sources:

• Executive Staff Memorandum No. 8, 8/23/33, Pan American Airways, Inc. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/67393/rec/4 https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/67393/rec/4

• Bender, Marylin, and Selig Altschul. The Chosen Insrument, Simon and Schuster, 1982.

• Brock, Horace, Flying the Oceans, Steinhour Press, 1978.

• Find a Grave, Ann Elizabeth Archibald at Arlington National Cemetery.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/43672185/ann-elizabeth-archibald#view-photo=199627418

• Kauffman, S.B., Pan Am Pioneer, Ed. George Hopkins, Texas Tech University Press, 1995.

• New York Times, ”Mrs. Ann M. Archibald," January 19, 1953, Page 23.

https://www.nytimes.com/1953/01/19/archives/mrs-ann-m-archibald.html

• “Over 400 Dolls in Archibald Collection,” The Clipper, Vol.1, No.3 (Aug. 1953), p. 3. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/16838/rec/18 [Mrs. Archibald's doll collection was later bequeathed to Pan Am Executive Vice President Sam Pryor].

August 16, 1933

"Fourteen Months in the Air"

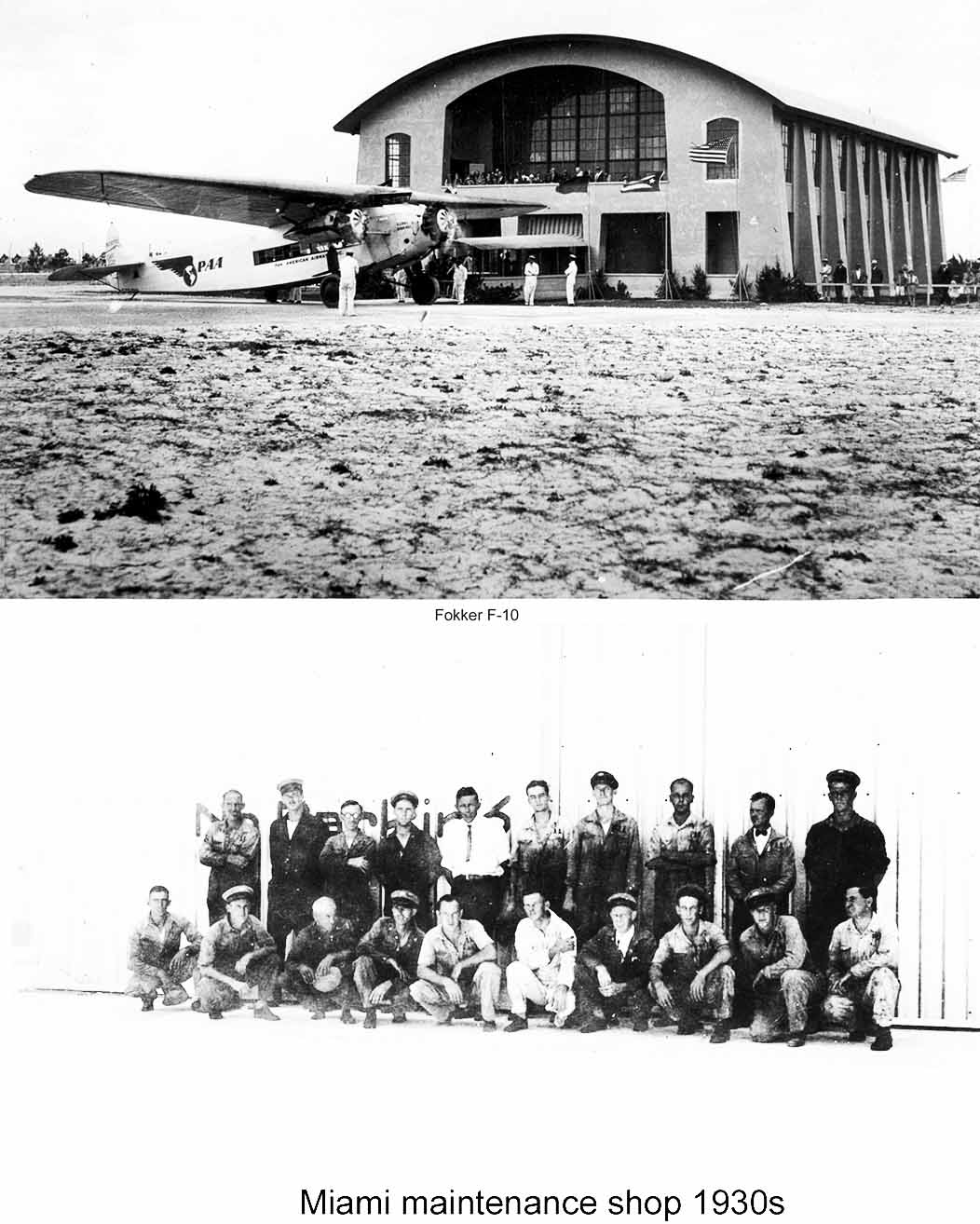

Portraits of Ed Musick (left) and Basil Rowe (right) "Two Pilots Pass 10000 Hour Mark" ("Pan American Air Ways," October 1933, p.9).

A U.S. Department of Commerce post announced that two of the country’s twenty-one licensed commercial transport pilots with more than 9,000 certified flight hours were Pan Am employees, and with more than 10,000 hours each, they were the group’s vanguard, what "Pan American Air Ways"(Vol. 4, No. 5) heralded as the “select circle of birdmen.”

Captains Edwin “Ed” Musick and Basil Rowe (#2 and #1 in pilot seniority – for more on this ranking see: March 16, 2022 post in the PAHF Digital Library exhibitions: https://exhibits.panam.digital/great-expectations/pan-am-1932/index.html ) were the United State’s first pilot generation, learning the art and craft before World War I and finding ways to live as full-time aviators after the war’s end by barnstorming, rum running, and one-off charter jobs, before each helped commercial aviation emerge as a viable industry.

By the time both joined Pan American Airways (Musick: June, 1927; Rowe: September, 1928) multiple log books recorded their flight histories. Musick’s showed 4,634 hours before his first Pan Am flight. Many of Rowe’s pre-PAA hours documented the development of West Indies Aerial Express, the first commercial airline in the region.

Pan American Air Ways put Rowe and Musick’s piloting activity in perspective by noting “that each has lived in the air a time equal to a year and two months, day and night, or a time equal to 3½ years of 8-hour working days.” During that time, Basil had flown “more than 100 different models of aircraft and [had] made more than 21,000 individual flights.” Ed had “completed 900 foreign round trips over Pan American schedules out of Miami, and [had] carried more than 10,000 passengers without incident of any kind.” All of this activity put both men over 1,000,000 air-miles flown.

For more about Captain Musick’s life, read William S. Grooch’s biography, “From Crate to Clipper With Captain Musick, Pioneering Pilot,” Longmans, Green & Co., 1939.

For more on Captain Rowe, read his autobiography “Under My Wings,” Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1956.

Source & Photo: “Pilots Musick and Rowe Pass 10,000 Hour Mark,”Pan American Air Ways, Vol. 4, No. 5, October, 1933, p. 9 (PAHF Collection). Also digitized at https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41151/rec/5

August 23, 1933

"Change is Here"

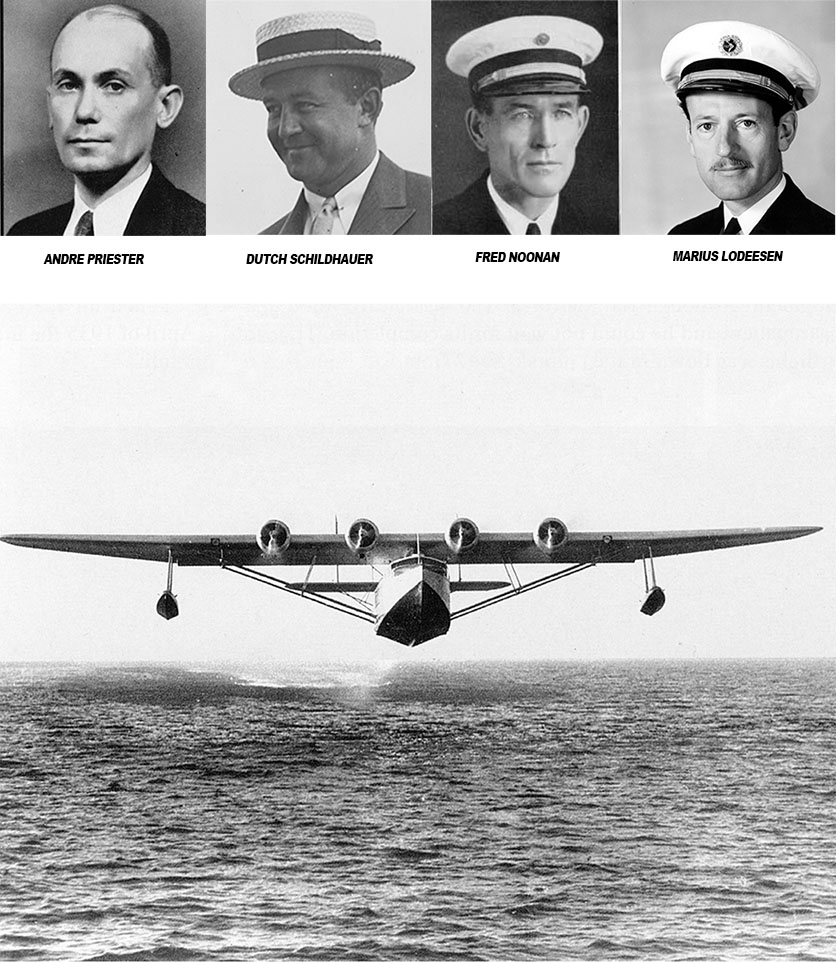

Photo of Pan Am Sikorsky S-42 and Andre Priester, Dutch Schildhauer, Fred Noonan and Marius "Lodi" Lodeesen (PAHF Collection).

By 1933, Pan American Airways was moving toward transoceanic service: Charles and Anne Lindbergh were scouting a North Atlantic route to Europe; service in China was starting, along with hush-hush scouting to connect North America to East Asia; and, new passenger aircraft were under construction (Sikorsky S-42 and Martin M-130) designed to fly more than 2,000 miles nonstop in difficult conditions. If successful, Pan Am’s transoceanic ambitions would announce a new era in commercial aviation.

Chief Engineer, Andre Priester, believed doing so required a new generation of flight crews. Priester wanted aircraft led by the best pilots possible whose training and experience matched that of oceanic ship captains. Pan Am’s transoceanic captains needed mastery over every crew member’s job function and going forward pilot hires would be college graduates with military experience. Assistant Operations Manager, Caribbean Division, Clarence H. “Dutch” Schildhauer, was assigned to bring the vision to fruition.

Schildhauer’s selection made sense. He was not a company pilot although he was a veteran naval aviator known and trusted by Pan Am’s Navy/Marine-trained line pilots. Dutch was a Naval Academy graduate who started as an enlisted seaman and retired in 1930 as one of the U.S. Navy’s top test pilots working on open-water endurance flying and navigation challenges. Moreover, Schildhauer had an international reputation: when the massive German flying boat, the Dornier Do-X crossed the South Atlantic in 1931, it did so with Dutch Schildhauer as second pilot and navigator. He brought accumulated wisdom and perspective and precision that Pan Am needed.

He understood Priester’s goal and, assisted by Fred Noonan, organized the intense “ocean training” program to develop a new pilot class – “Master of Ocean Flying Boats.” The program produced what Captain Marius Lodeesen, one of the first six program participants, stated with certainty: “There had never been a flying group like ours…a hybrid between the skippers and the ground staff.” By the time pilots completed this program’s first phase and began to fly the line they held federal licenses in airframe and engine maintenance and radio operations, and were trained in maritime law, signals (radio and semaphore), navigation, meteorology, even knot tying. Training continued via ground and correspondence course as these pilots amassed the seven years of full-time flying set as the baseline for “Master of Ocean Flying Boat” status.

Sources:

• Banning, Eugene. “Airlines of Pan American Since 1927,” Paladwr Press, 2001, p. 66 & 77.

• Lodeesen, Marius. “Captain Lodi Speaking,” Paladwr Press, 2004, p. 51.

• “Clarence H. Schildhauer, 84, pioneer in aircraft industry,” The Evening Sun (Baltimore), May 1, 1980, p. 8.

August 30, 1933

"Express (Espresso) Service: Pan Am’s Bean Bag"

Photomontage: Commodore (PAHF Collection). Coffee images generated at Craiyon.com.

As Brazil burned millions of pounds of prime coffee beans to stabilize • commodity prices in 1933, Pan American Airways pilots flying less-than-airtight Consolidated Commodores and Sikorsky S-40s sniffed their way into the landing zone in Santos Harbor, the center of the world’s coffee trade.

October 1929’s global economic collapse revealed the country’s deep indebtedness, decades-long coffee overproduction triggered a 70% price drop per/100-lb/bag, and the government’s “valorization scheme,” guaranteed a “floor price” regardless of demand.

Brazil needed to export coffee to its largest trading partner and creditor, The United States of America, not destroy it. However, U.S. coffee consumption, the world’s 1919 per-capita leader had contracted: still, Pan Am Traffic Representative, A.E. Peterson smelled a northbound, premium-revenue freight opportunity.

After a four-month development period, Pan Am announced a “new package … for air express shipments of coffee samples,” described as “a neat canvas sack … made in Brazil … and bears the national seal and the inscription `Brazilian Coffee’ or, one side, and on the other, the legend, `Via Air Express, Pan American Airways System,’” with “an interior coating of waterproof cellophane (that) insures the coffee against moisture seepage, and brings it to the New York market in the best possible condition.”

Peterson had discerned that New York coffee brokers “welcome(d) receipt of shipments by air express, even paying the express ship charges north of Miami” and “shippers in Brazil are increasingly willing to pay their share of the air express charges, since sending the samples by air permits selling the coffee before it arrives in the market, thus saving from two weeks to a month in getting their money to the growers.”

Pan Am’s coffee-sample express service soon expanded to other countries.

Sources:

• Banning, Gene. “Airlines of Pan American Since 1927” (Paladwr Press), 2001, p. 66.

• "Pan American Air Ways," Vol. 4, No. 3 (June 1933), p. 29. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41053/rec/3 https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/41053/rec/3

Go back to "90 Years Ago" main page