January 11 marks the anniversary of the tragic loss of the Samoan Clipper

Pan Am Pilot Ed Musick was careful, capable, and attentive.

His widely publicized achievements set the tone for the profession to evolve so that the aviation industry it served could grow. It’s no wonder that all these years later his name still conveys significance, respect, and even inspiration.

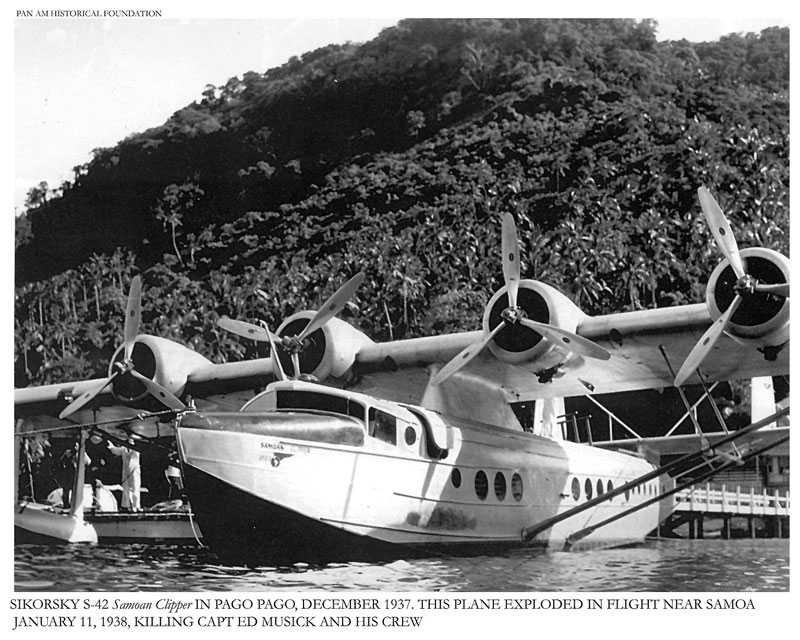

On its second run “down under”, carrying the mail on a new Foreign Airmail route to Auckland, New Zealand, the Sikorsky S-42B’s #four engine sprung an oil leak just after leaving Pago Pago’s tea cup-shaped harbor.

Capt. Ed Musick, following procedure, decided to dump fuel to lighten the landing weight of the 19-ton flying boat. For reasons never definitely understood – perhaps because explosive fumes in the Sikorsky’s wing spaces were ignited by the electric flap motors - the plane suffered a catastrophic fire. The flaming aircraft plunged into the sea with the loss of all aboard.

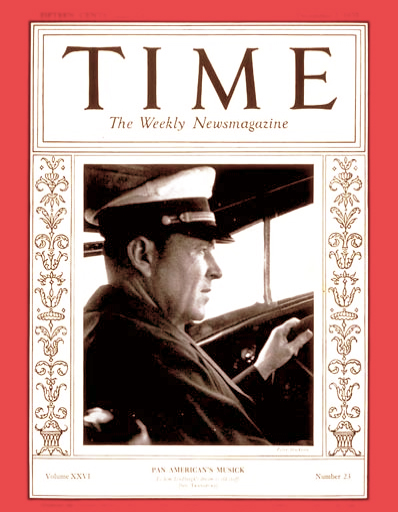

The news stunned not just Pan Am, which at the time was a relatively small company, but the whole world. A laconic, meticulous, but above all authoritative commander of transoceanic aircraft, Ed Musick was the epitome of an airline pilot. He had been honored on the cover of TIME when he pioneered the opening of Pan American Airways’ first transpacific route in 1935. He had received the coveted Harmon Trophy. He was a first among equals in an elite group in whose hands were placed the responsibility of safely and regularly maintaining intercontinental communications by air – an evolutionary leap for the air transport piloting profession that didn’t exist before his tenure.

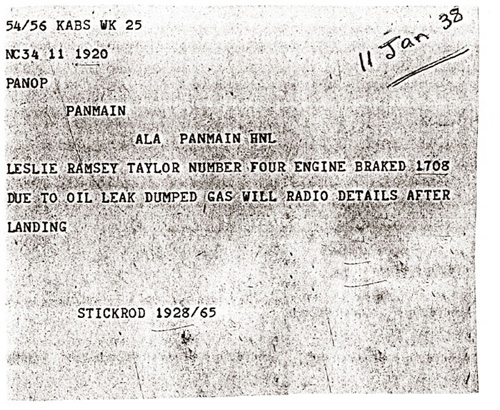

Final Radiogram from the Samoan Clipper, Courtesy of G. W.Taylor

Ed Musick's untimely death provided a very clear example of the potential dangers inherent in the line of work he and his colleagues had chosen. It underscored the brick wall of a fact that no matter how much you prepare, you may not be able to comprehend the consequences of every factor affecting your situation – and in the aviation business, one of those factors just might kill you. Flying was (and remains) serious business, which demands strict adherence to proper routine and knowing what you’re about. Ed Musick understood that professionalism demands that you take your job seriously. He did, and the sacrifice he and his six colleagues made underscored the need for further understanding of the risks they inadvertently exposed, but that wasn’t because they ignored them.

What we can thank Capt. Musick for now, all these years later, is his legacy as a professional. Like a great many fliers who came up in the years after the “Great War,” he had to struggle some to find a way to make a living doing what he most wanted to do. (He might have done a little aerial rum-running.) It was a time when people flocked to see “air circuses,” and when hundreds of people tried stunt flights challenging time and distance to stay in the air, hoping to make headlines and a few dollars. All of that imbued aviation with more than a faint tinge of devil-may-care fatalism. It sold newspapers, and made heroes of some, and casualties of more than a few.

What we can thank Capt. Musick for now, all these years later, is his legacy as a professional. Like a great many fliers who came up in the years after the “Great War,” he had to struggle some to find a way to make a living doing what he most wanted to do. (He might have done a little aerial rum-running.) It was a time when people flocked to see “air circuses,” and when hundreds of people tried stunt flights challenging time and distance to stay in the air, hoping to make headlines and a few dollars. All of that imbued aviation with more than a faint tinge of devil-may-care fatalism. It sold newspapers, and made heroes of some, and casualties of more than a few.

What it didn’t do was to build confidence in aviation as a sound business endeavor, a safe activity, or even a reliable means of transportation. Even after Charles Lindbergh ignited a storm of interest with his solo transatlantic flight in 1927, the actual business of flying still seemed in large respect the domain of thrill-seeking daredevils. As a case in point, take the 1939 hit movie “Only Angels Have Wings.” Cary Grant, as the operations manager of a small South American airline has to rely on a stable of pilots who think nothing of risking their lives flying in bad weather over treacherous terrain in unreliable aircraft. As the movie pointedly portrays the situation, injury or death is usually right around the corner. You might get through today, but tomorrow you might not be so lucky.

Of course, that movie was about a fictional situation, but the idea seemed plausible enough to most people in the 1930’s. Aviation was viewed as a dangerous game, played by people with nothing to lose. For a great many folks, even getting into an airplane and leaving the ground was a challenge. We have the testimony of a professional aeronautical engineer, setting forth on his first transpacific flight on a Pan Am clipper in 1938 who admitted that: “As we headed out to sea . . . I had many misgivings . . . the thoughts of leaving the California coast with 2,400 miles of open ocean ahead were somewhat discomforting.”

Ed Musick had been quietly and successfully soothing public anxieties about flying for several years before he died. More than that, he had been setting a standard for professionalism and competence for all who made a living in his line of work, and it did a lot to counter the long-prevailing meme of pilots as death-defying, fool-hardy risk-takers.

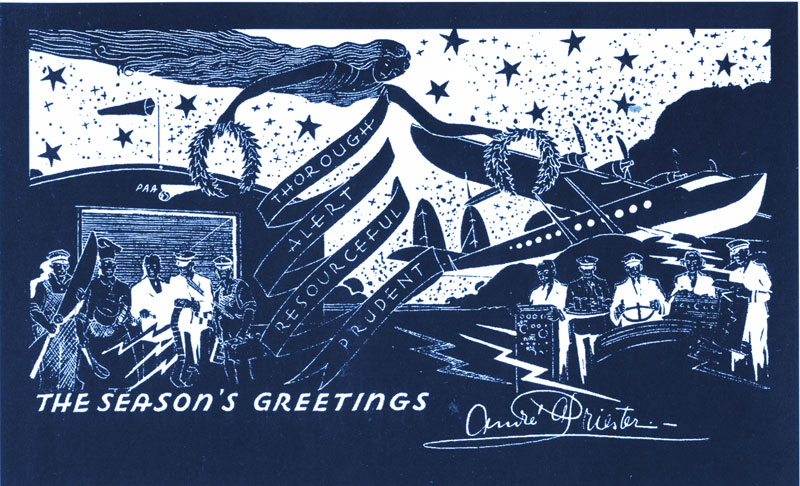

"Thorough, Alert, Resourceful, Prudent." Andre Priester's Holiday Card of Pan Am's Sikorsky S-42, Courtesy of the Leslie Family Collection.

His approach to life and work was a perfect fit with the ideals presented on a holiday card sent out by Pan American’s Chief Engineer and number-one safety evangelist André Priester. The card showed an S-42, the Pan Am logo, and some symbolic Pan Am employees, along with these words: “Thorough,” “Alert,” “Resourceful,” and “Prudent.” Musick was the living embodiment of those ideals. Priester was known for promulgating a saying that: “Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But . . . it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect.”

Captain Edwin C. Musick provided an emblematic suggestion of commercial reliability in an age when the airline industry sought any and every opportunity to emphasize safety and regularity. Any chance to link those qualities with a commercial enterprise that made use of air transport was a win-win for all parties. This publicity photo showing a representative of the Dole Company (which shipped a lot of pineapples from Hawaii to the Mainland) must have been taken with that as background motivation.

Ed Musick and Governor William Poindexter of Hawaii beside the China Clipper, March 7, 1936, with pineapple juice to be delivered to Sec. of the Interior Harold Ickes in Washington DC, by Hawaii's Congressional Delegate Sam W. King

(Info courtesy of Bishop Museum, Hawaii & photo from San Diego Air and Space Museum)

FOOTNOTES

Musick Memorial Radio Station Auckland NZ 2009 by Russell Street (Wikimedia)

MUSICK MEMORIAL RADIO STATION

Ed Musick captured the hearts of New Zealanders in March 1937 when he opened a new air route connecting North America with New Zealand. Less than a year later, his tragic death was followed by deep sympathy and discussion of plans for a national memorial in the form of a "radio beacon" to honor the great aviator and his crew who had done so much for transpacific aviation. Personal donations were solicited by the Auckland Herald, which in turn funded additional ideas for memorials, such as the Musick Memorial Trophy.

In January 1942, New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser officially opened the Musick Memorial Radio Station honoring Musick and his crew. Subsequently the memorial building and grounds in Auckland housed New Zealand radio communications for over 40 years. The Art Deco structure and landscape inspired by aerodynamic design — an airplane and its wake — became an important base of operations for intercontinental communications, especially during World War II (Aviation, Auckland ZLF & Maritime, Auckland ZLD). The building is now occupied by the Musick Point Radio Group (http://musickpointradio.org/)

At the dedication, Prime Minister Fraser announced: "This tablet erected by the Government of New Zealand commemorates the Samoan Clipper lost with her crew January 11th 1938. Capt. Edwin Musick, Capt. C. Sellers, P.S. Brunk, F.J. MacLean, T.D. Finley, J.W. Stickrod, J.A. Brooks." With a quote by the poet Robert Bridges:

"Now ye are starry namesBehind the sun ye climbTo light the glooms of timeWith deathless flames.’"