Kingman Reef as it appears today

“Pacific” means peaceful. But of course, the world’s biggest ocean is anything but. Typhoons, and tsunamis, and other natural hazards all belie the notion Spanish Conquistador Balboa had of a peaceful ocean. And there are even greater forces clashing under the ocean: the tectonic battle of creation and destruction – building and destroying islands as the Earth’s tectonic plates relentlessly move in their geologic dance.

In human terms, the idea of Pacific battles brings to mind the epic conflict of World War II, with mighty navies, massive battles on land, sea and in the air.

But this story is about another, much less recognized war in the Pacific. It didn’t last long, but it was a struggle, and demanded sacrifices before eventual success. Like a lot of Pan American’s history, it’s a story of a struggle to open an air route across an ocean that no one had done before.

At the start of 1937, Pan American Airways had been successfully operating its small 3-plane fleet of Martin M-130 flying boats in the northern transpacific route for less than a year and a half, and had only been carrying passengers to Manila since October of the previous year. But the airline’s management – meaning Juan Trippe - decided to reach for a further goal, and open a route to New Zealand in the Southwest Pacific. He wanted to push Pan Am’s routes to Auckland before Britain’s Imperial Airways, coming via Australia from the other direction, could do it.

The SS North Wind in Kingman Reef Lagoon

And another foreign airmail route would mean new revenue for America’s only international air carrier. New Boeing clippers were on order to provide aircraft to do the job (although their delivery would be delayed till 1939). And there was time pressure: Pan Am’s arrangement with New Zealand demanded the start of mail service begin by the end of the year. Not only that, the new Sikorsky S-42B which would make the survey flights to Auckland had to be available shortly thereafter to provide a new shuttle service between Manila and Hong Kong, to comply with another agreement Pan Am had worked out with the British colony.

Following the successful approach used to create the route to Manila, it was deemed best to chart a course using American-controlled bases. This route meant flights from Hawaii, via Kingman Reef, and Pago Pago in American Samoa, to reach Auckland. Unlike the relatively big atolls available at Midway and Wake, where large bodies of protected water sat inside surrounding islands, the route to Auckland had extra challenges.

Kingman Reef lay 1,100 miles southwest of Hawaii, and as the name implies, can hardly be described as land. Barely above sea level, it’s a ring of very low-lying coral rubble, surrounding a lagoon. Unlike Wake or Midway, there is no terra firma available for permanent buildings. To use it as an airbase meant stationing a sea-going vessel there, for crew rest, communications, and refueling capabilities. As with Wake, precise navigation was critical to find it.

Another 1,400 miles to the southwest was American Samoa, where the capital Pago Pago sits ensconced among high steep hills on three sides, with the open ocean breaking over reefs on the remaining side. Landing or taking off from Pago Pago’s harbor in a flying boat required tremendous skill and experience. The approach required a short, steep, precise turning dive, and a quick stop once on the water, to avert catastrophe. The last leg of the trip to Auckland was a long 1,800 miles, but a takeoff to fly in either direction required a heavy fuel load. Making a landing at Pago Pago with a heavy “ship,” (as would be the case if a flight had to be canceled shortly after takeoff if no fuel was dumped) would mean disaster.

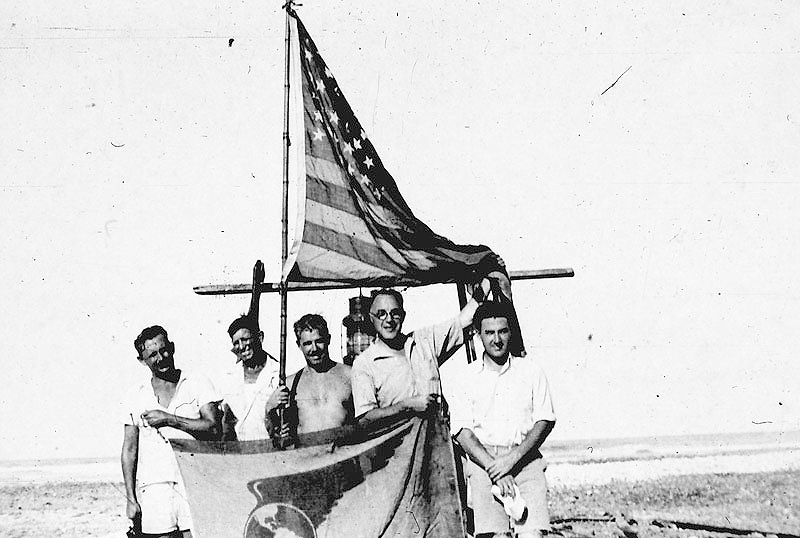

On March 11th, 1937, Pan Am’s chartered freighter the “SS North Wind” (sister ship to the “North Haven”) set out from Honolulu with all that would be needed to support the survey flight as a base at Kingman Reef. Six days later, the new S-42B, christened “Pan American Clipper II,” Captain Edwin Musick in command, set out from Alameda for Honolulu. Ominously, with only two hours left to go, she sprang an oil leak in the number two engine, which had to be shut down for the balance of the flight.

It’s interesting to note that while in Honolulu, Ed Musick expressed an uncharacteristic tentativeness about his mission to a reporter from the local paper. “The continuation of the flight to New Zealand, via Kingman Reef and American Samoa, is undecided. We will await orders from Alameda” he said. Musick was always laconic, but he was usually more upbeat about his work. He understood the challenges he faced opening this route were greater than those he had faced previously.

Engine repairs delayed the next leg of the trip in Honolulu, but the survey flight got under way again for Kingman Reef early on March 23rd, 1937.

Capt. Edwin Musick comes aboard the North Wind

They arrived over Kingman at 1:20 pm, in a driving rain. Musick circled for almost another half-hour before landing in the lagoon. The crew was picked up by a boat from the “North Wind.” The small group of Pan Am personnel did their best to make Musick and his crew feel welcome. Dan Vucetich, head of the “base,” had saved a couple of flower leis from Hawaii to drape around Musick’s neck as he came onboard the ship. They all shared a dinner of steak and fresh fish, and the flight crew were given the best accommodations available onboard the spartan Alaskan freighter. But no one wanted to extend the stay.

The next morning, with rain still pounding down and clouds down close to sea level, Musick and his crew were taken back to their aircraft. Always his careful self, Ed Musick took an hour to warm up the four Hornet engines before he felt ready to depart.

When they did, as Vucetich noted in the diary that he kept: “The sky was overcast, the sheets of rain swept by the wind obscured all visibility. It must have been hard on Captain Musick and his men. Suddenly like a gigantic eagle, the Clipper took off and disappeared into the rainloaded clouds . . . The excitement is over. Up since early this morning. I did not read, I did not fish. Just went to bed early.”

87+ Years Ago: Dan Vucetich and Crew at Kingman Reef, March 23, 1937

The “North Wind” would stay on station as the “Pan Am Clipper II” flew back to Honolulu on the return trip.

Captain Musick would return to Kingman Reef nine months later, on what was to be the first official mail flight from New Zealand to the US. This time, the same S-42B was now named “Samoan Clipper.” The chartered freighter “North Wind” was now replaced by the four-masted schooner “Trade Wind.” But the challenges to flying the route remained the same: the minimal rest and challenging navigation of Kingman Reef; and the tortuous harbor at Pago Paga had to be managed to reach Auckland.

Musick handled the second New Zealand flight with his usual professional competence. He left Honolulu two days before Christmas, and was back there two days after New Years, 1938. He was tired, and was due for a very well deserved break. Just over a month before, he managed to fly the Hawaii Clipper through a typhoon – a flight that taxed him and the plane close to breaking.

But he was asked to do the Auckland trip once again, with hardly a break. He and his crew departed Honolulu on January 9th. They made it back to Kingman Reef one last time that day, and flew to Samoa the next. The following day, January 11th (in the US), they took off for Auckland.

As had happened before in March, one of the Clipper’s Hornet engines sprang an oil leak. There was no choice but to dump fuel and return to Pago Pago.

It was the end for the “Samoan Clipper” and her crew. The plane fell into the Pacific, a ball of fire. The US Navy ship sent out to the scene found an oil slick and a few bits of wreckage. The clipper and all aboard were gone.

It was a terrible loss. Even Juan Trippe knew he would have to defer his vision of flights to New Zealand. It was a desperate act to operate an air route using Kingman Reef and Pago Pago as bases. The whole enterprise was put on the shelf to await a better plan. Ed Musick and his fellow crewmates were casualties in this battle with the ocean, and the Pacific had come out the winner.

There would be another chapter in the struggle. A new aircraft – the Boeing B-314 “super clipper” along with other, better stopping places would be available by the summer of 1939. This time Pan Am would come out the winner. But every flight that made the journey successfully owed a debt to those who had fought the battle before, and had paid the price so that others could follow.

Related articles

Samoan Clipper Hunt: July 2019