Chronicling Wake Island - A Brief History

Photo: Wake Atoll with Pan Am Boeing 314 NC18609, May 25, 1941. “View of Peale Island, Wake, taken 25 May 1941. Seven U.S. Navy Consolidated PBY patrol planes are anchored in the lagoon, and a Pan American Airways Boeing "Clipper" is docked at the pier. The Pan American compound is at the foot of the pier.” ( U.S. Navy photo, U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command).

If you are flying west across the International Dateline, the first piece of American soil you could encounter is Wake Island. Actually an atoll, the three bits of land comprising Wake – Wake, Peale, and Wilkes Islands – altogether add up to less than 3 square miles of ground. It’s geographically related to the Marshall Islands, most of which lie well to the south of Wake.

NASA Satellite Image of Wake Island location in the Pacific. 2019.

NASA Satellite Image of Wake Island location in the Pacific. 2019.

Way Back When

Like its neighboring atolls to the south, Wake exists thanks to the ceaseless work of the corals that have grown up on top of a submerged volcanic mountain. As the extinct volcano eroded above the waves, it was also sinking due to subsidence of the seafloor on which it rests. The corals find this environment a happy place to make their home, and over millennia built up the bits of land that remain above the waves. The result is a lagoon of calm water surrounded by strips of sandy ground – a watery garden of sorts sitting in the midst of the vast Pacific.

The official European discovery of Wake is credited to eponymous British sea captain William Wake in 1796. Marshallese seafarers had been there already, but had not settled the atoll. No wonder, as it is isolated from the rest of the Marshall Islands by hundreds of miles of open ocean, and has no natural fresh water.

The likely first encounter by Americans came with wide-ranging New England whaling fleets in the early 1800’s, but the place was officially recognized, if not claimed, by the United States Exploration Expedition under US Navy Commander Charles Wilkes in the 1840s. Renowned illustrator, Titian Peale, was the expedition’s official naturalist/artist -- hence the name of two of the atoll’s islands, Wilkes and Peale.

The Marshall Islands, Wake included, went through some nominal cartographic changes in the latter decades of the 19th century. Spain had claimed most of Micronesia for three hundred years, but ceded sovereignty to Germany in the 1880s when the guano and copra trades began to flourish, and Spain was losing its long colonial grip. This included Wake, but even the industrious German administrators ignored the place, as it was devoid of any marketable resources, not to mention fresh water and locals to do the work.

Then in December 1898, the US Navy dispatched the USS Bennington to help settle the new US administration of Guam, which had only just been wrested from Spain during the brief Spanish-American War. What was needed, it was understood in Washington, was a good place for an undersea cable relay station to help maintain communications with the new territories in the Western Pacific. Wake seemed to be the right location.

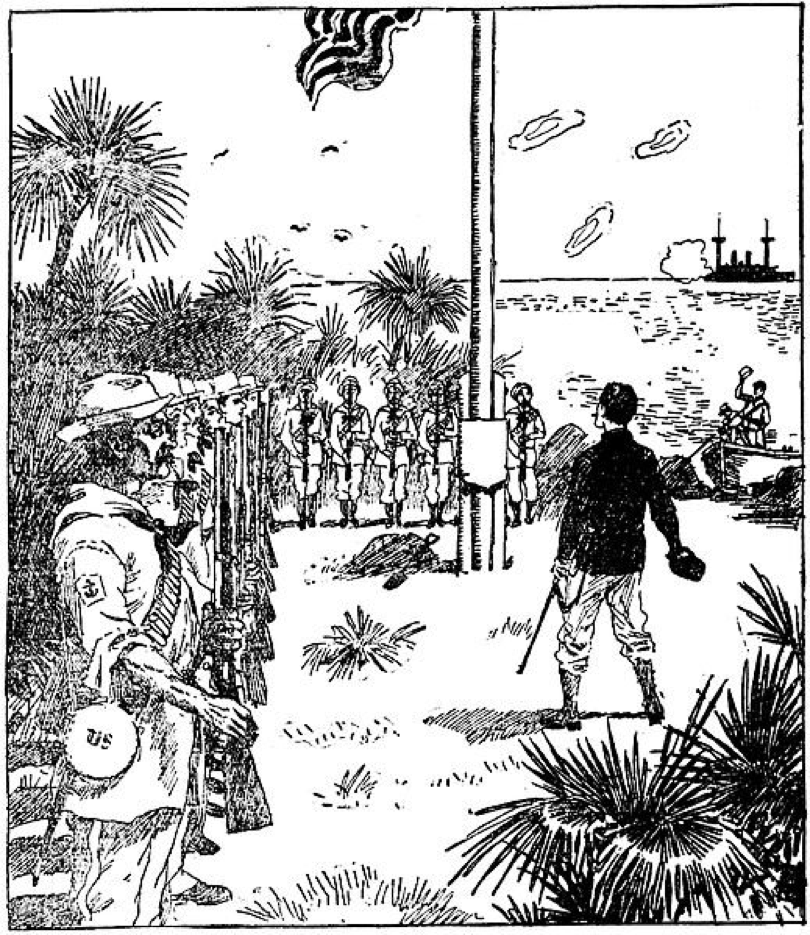

Commander E. D. Taussig, USN, of the gunboat USS Bennington (PG-4), having called all present to witness that Uncle Sam took possession of Wake Island, ordered Old Glory to be hoisted by Ensign Wettengel. From “How Old Glory was Raised on Wake Island", Los Angeles Herald, May 14, 1899, page 14. (Wikimedia).

Commander E. D. Taussig, USN, of the gunboat USS Bennington (PG-4), having called all present to witness that Uncle Sam took possession of Wake Island, ordered Old Glory to be hoisted by Ensign Wettengel. From “How Old Glory was Raised on Wake Island", Los Angeles Herald, May 14, 1899, page 14. (Wikimedia).

Apparently the orders provided to the Bennington’s captain, Commander Edward Taussig, included the mission to stop by on the way past and “annex” Wake for the US. This was done, January 17, 1899. Taussig and a small party landed, put up a small pole with the Stars and Stripes nailed to it, along with a brass plaque claiming the island, while the ship gave a 21-gun salute. They then returned to the Bennington and sailed away to Guam. All “done and dusted” in the span of just over four hours. The seabirds could go back to their business, which apparently included occasionally being plucked for their valuable feathers by Japanese collectors, who ranged throughout the Central Pacific in those years, at a time when fashion favored plumage on ladies’ hats.

There was some diplomatic wrangling thereafter during the first years of the new century in far-off Berlin regarding the legality of America’s possession of Wake (which the Germans had assumed they’d bought from Spain), but the protagonists had bigger fish to fry, and the question soon fell off the official agendas.

In 1923, the Bishop Museum in Hawaii mounted an expedition that included Wake, with the cooperation of the US Navy, which provided the USS Tanager as a research vessel. While the scientists undertook botanical and zoological observations on land, the Navy made soundings offshore. This came at a time, just after the First World War, when the international balance of power was undergoing a radical shake-up. In the Pacific, the big change was the emergence of a newly powerful Japan. It wasn’t lost on strategic thinkers on either side of the Pacific that places such as Wake were no longer just dots in a vast ocean.

Pan Am & The Air Age at Wake

At the time, much of naval aviation strategy relied on flying boats. Although aircraft carriers were in their early stages of development, it seemed that long-range seaplanes could provide an effective means of projecting naval strength over long distances. They could scout, track, and even attack enemy forces at sea, without needing air bases on land. What they did need were calm bodies of water from which to operate. Atolls such as Wake were seemingly ideal for that role. There was enough land surrounding a large lagoon to warrant Wake’s consideration as a base for flying boats. Of course, those flying boats could be carrying out military missions, or flying commercial routes. So this small bit of land with its lagoon provided enough territory to make the place an item of intense interest during a few short years in the mid-20th century.

When Juan Trippe decided to take the bold step of opening a commercial air route across the Pacific to Asia, he needed stepping stone bases for rest and refueling of Pan Am’s newly acquired Sikorsky and Martin flying boats. For that, Wake was tailor-made – almost. All that was needed was a massive and complex undertaking to mount several seagoing expeditions employing hundreds, and costing millions. Along with that, Trippe needed to negotiate arrangements with his own as well as foreign governments, all done at a breakneck pace. And this was undertaken as a speculative investment, which rested in large part, on having lonely Wake Island to use a base.

Pan American Airways (PAA) hotel and facilities on Peale Island, Wake Atoll. Hotel is on left, anchor from Libelle shipwreck and pergola leading to "clipper" seaplane dock is on right. (U.S. National Archives, U.S. Navy photo).

Trippe and his Pan Am colleagues created a new Pacific Division to tackle the job. By early 1935, the organization had developed intricate plans to turn Wake, along with Midway (another atoll) to the east, and Guam, off to the west, into links in a chain that stretched from San Francisco Bay to Hawaii, and across to the Philippines. Of these, Wake was the most challenging.

Midway had a long-established undersea telegraph cable relay station. Guam had been a US naval base for even longer. But Wake was very much an unknown. Whatever might be needed there would have to be shipped in, off-loaded at sea, landed, built, and made ready without recourse to outside help. It was a massive challenge. It would take three missions with a chartered freighter, the SS North Haven, to get all the needed materiel and supplies to Wake and the other mid-Pacific bases.

Pan Am China Clipper berthed at Wake, photo taken in 1936 (William Voortmeyer Collection/ PAHF Collection).

But beginning in late November 1935, the transpacific air route was a going concern. First with Martin M-130s, and later with the larger Boeing B-314s, Wake’s lagoon hosted transiting flights carrying mail, cargo, and passengers to and from Asia. And so began a brief but halcyon phase of international aviation. Pan Am touted Wake as a vacation paradise where one could relax, sunbathe, fish and sail in the lagoon, and while away idyllic hours in pampered luxury in the hotel the airline had built on Peale Island.

Wake Island’s days as a Pacific idyll were short lived. The atoll sat within easy flying distance from the Japanese-controlled bases in the Marshall Islands. Japan’s military strategists understood that their grip on the mid-Pacific would be threatened by a US military presence on Wake. And for their part, the same realization had come to America’s naval strategists.

War Comes to Wake

“Aerial photo Of Wake taken from the northeast in May 1941 from a U.S. Navy PBY Catalina flying boat. Wishbone-shaped Wake Island proper lies at left, as yet unmarked by construction of the airfield there. The upper portion of the photo shows Wilkes Island; at right is Peale Island, joined to Wake by a causeway. (U.S. National Archives Photo 80-G-451195, Wikimedia).

By early 1941, it was clear that Wake was vulnerable and if it was to be part of any viable defense strategy, it needed immediate reinforcement as a military base. Now under contracts with the US War Department, hundreds of contractors poured onto the small atoll. They feverishly worked to build a military airstrip, fuel and ammunition bunkers, gun emplacements, roads, and all the other assets needed to make Wake a military stronghold. But time was running out.

The same day the Japanese naval task attacked Pearl Harbor, a squadron of Japanese warplanes made a surprise attack on Wake, strafing and bombing whatever targets they could find. That first attack left many dead and wounded, and several buildings destroyed. War had come to Wake.

The small Marine garrison, supported by hundreds of civilian contractors now trapped on Wake, fought valiantly for two weeks. They fought off one large Japanese invasion force, inflicting hundreds of casualties and sinking several vessels. But in the end, left to fend for themselves without help from outside, they had to surrender to overwhelming Japanese forces. Wake became known as the “Alamo of the Pacific.”

Most of the Americans and Guamanians who had been captured were shipped off to Japanese prisons in Asia. Another contingent was kept on to labor for their captors. These men were later murdered in cold blood, after a punishing air raid by American forces in 1943 that killed many Japanese troops and inflicted severe damage. One of the intended victims of the massacre managed to escape long enough to scratch a memorial on a rock: “98 PW 5-10-43.”

In an ironic twist, Wake Island, Japan’s hard-won and would-be island stronghold, proved to be a useless asset. As the American naval counteroffensive swept westward across the Pacific, Wake became a backwater. Japan failed to resupply the garrison and their troops began to starve. In September 1945, US forces returned to retake the atoll.

Japanese Surrender at Wake, September 1945. (Photo: 96813 Naval History Center/R.O.Kepler, USMC).

Modern Wake Island: Peace Returns

Now began a new phase in the history of Wake. With peace came a new role. It was still perfectly positioned to act as a refueling stop for transpacific flights. The flying boats were gone, but new powerful landplanes such as the DC-4 and Constellation, and soon after, the Boeing 377 were using Wake’s runway. New facilities were built to replace those destroyed by war, although the war’s wreckage would remain as silent reminders.

Wake would once again flash into the world’s headlines as a result of international conflict. War had erupted in Korea, and US President Harry Truman needed to speak face-to-face with his top military commander, General Douglas MacArthur. The meeting was arranged for Wake Island given its relative proximity to Asia. On October 15th 1950, the two leaders flew in from opposite directions to confer. Although MacArthur would later write the president that he’d left their private meeting with complete “satisfaction,” their relationship was rocky. Truman relieved MacArthur of command the following April.

The moment that Douglas MacArthur and President Truman met on Wake, October 1950. (Photo Ed Swofford, photo restoration by Jack Crane/Pan Am Historical Foundation Collection).

But the sands of time were running out for Wake’s importance in the international scheme of things. With newer generations of longer-ranged aircraft, mid-Pacific refueling gradually became a thing of the past. Planes could fly high enough, and far enough, to by-pass the place. Pan American had reclaimed Wake as an important aviation asset after World War II, and kept it “online” for many years. For a time, Wake was a stop on the airline’s round-the-world service. During the Vietnam conflict, Pan Am’s jet freighter service used the base to refuel. But the days of Pan Am’s regular presence there were about to end. The China Clipper II, a Boeing 747 flew in during a November 1985 commemoration of the first commercial flight to Wake a half-century earlier.

Today Wake is a much quieter place. There is a military airbase there still, and it stands ready to host or help transiting flights by civil aircraft too. But the focus of the wider world has long since moved on, leaving Wake mostly alone, a place mostly for birds, as it was long ago.