When We Built the Transpacific Air Route

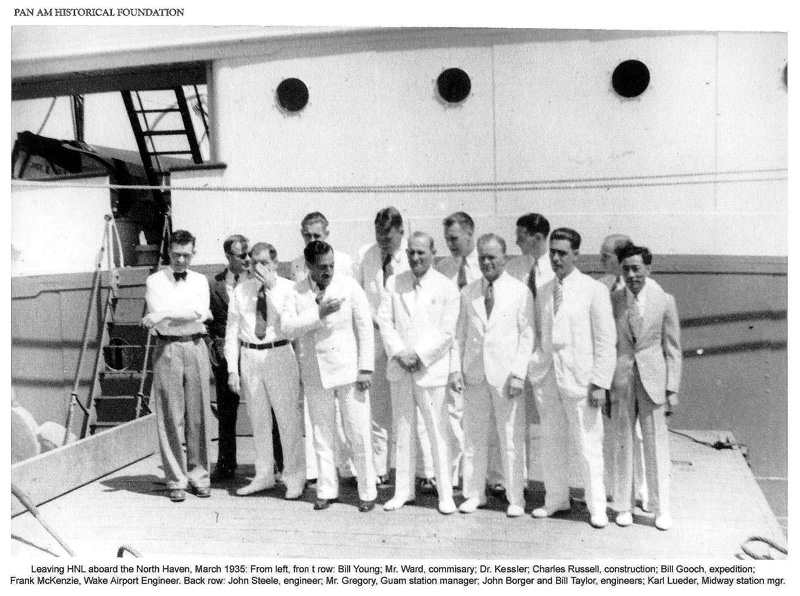

by John Borger (Originally printed in the PAHF Clipper Newsletter, Spring 1995)

When John Borger, a recent college graduate, was hired on by Pan American Airways to help plan the transpacific air route, he had no idea what he was in for. It proved to be an adventure of a lifetime, and opened the door to a career the would lead him to the pinnacle of aviation engineering decades later.

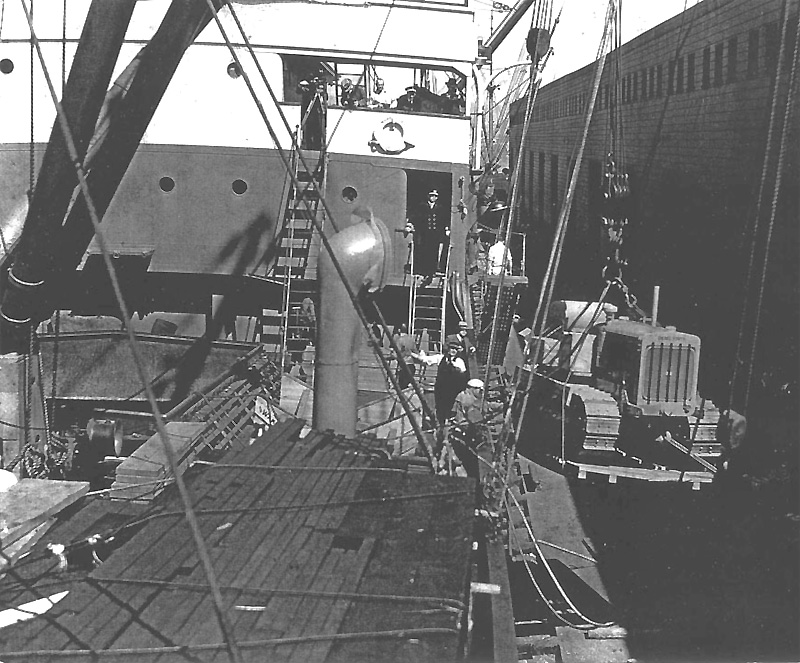

The SS North Haven loading in San Francisco, Pan Historical Foundation photo.

"What’s amazing is that eight of us in the Chrysler Building in New York City planned this expedition in two months. Captain L.L. Odell, Pan Am’s Chief Airport Engineer, was in charge of planning, and Charles Russell was in charge of the expedition. I was just out of college, and was chief clerk. I remember our Request for Capital Appropriation was over a million dollars, one of the biggest RCA’s at the time; the Board okayed it immediately.

The North Haven was the perfect ship for the job. The 6,700-ton freighter had been taking cannery workers to Alaska, and its lower deck was a dormitory with double bunks, and we had 112 plus the ship’s crew aboard. It had huge refrigerators, and we had to carry six months’ worth of food for Midway and Wake. We had to plan to load it so the things we’d need to unload first were loaded last.

On board the SS North Haven.

Honolulu and Manila were cities, of course, and Guam had a Navy base, so we only needed to install radio navigation and communications equipment there. But we had to build bases from scratch on Midway and Wake. Midway was a relay station on the transpacific underwater cable, and 23 people manned the cable station, so we had pretty good information about Midway. It had a deep lagoon and water. But Wake was totally uninhabited; all we had on it were a hydrographic chart with no detail, and an article in National Geographic magazine.

We needed Adcock direction finding stations at all the bases, and each station needed 16 antenna masts. I was told to acquire 35-foot poles for all the stations, and I did. They didn’t tell me they meant 35 feet above the ground, plus another five feet in the ground. We got the 40-foot masts in Honolulu. My 35- foot masts later became stringers to reinforce the docks at Midway and Wake.

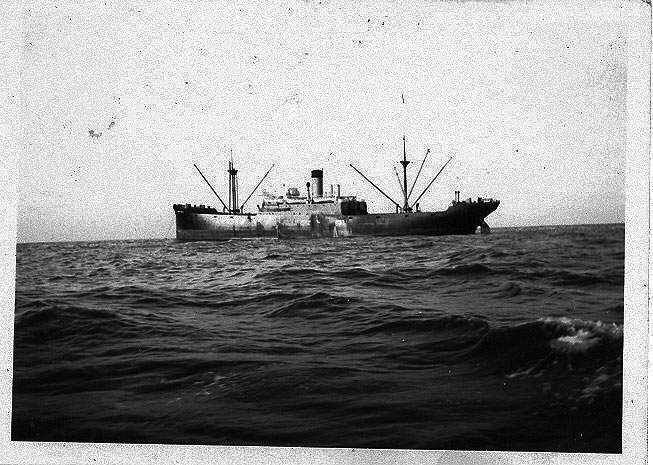

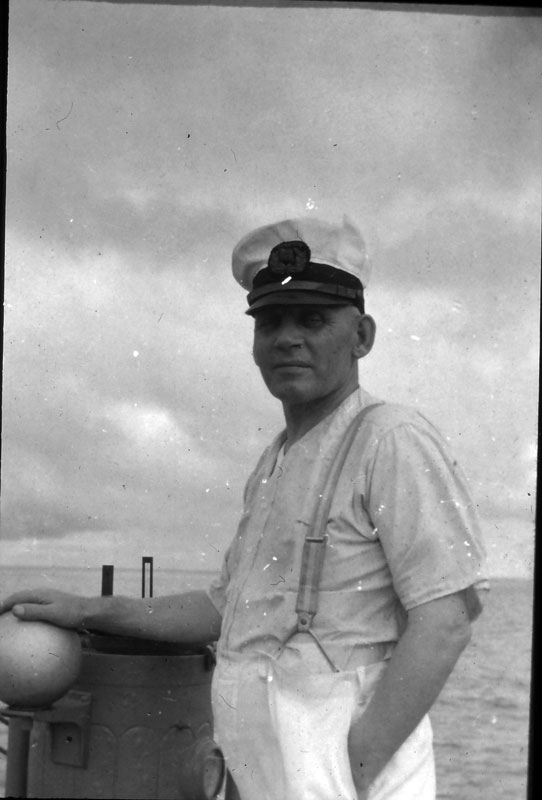

Capt. Borklund of the SS North Haven. Courtesy of the PAHF/Vucetich Collection.

The Adcock direction finder was phenomenal for its time. A radio operator in an airplane could hold down his transmitter key, and a ground operator could get a bearing within 1 degree at a range up to 1,500 miles. With bearings from two stations, the Clipper could fix its position with great accuracy. One perfect night a station in Alameda got a bearing from a Clipper between Guam and Manila, but that was exceptional.

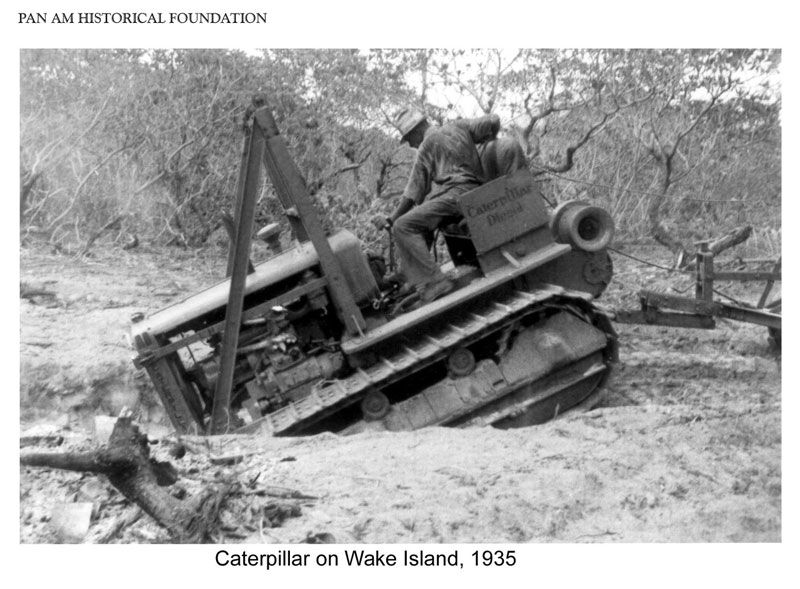

We loaded into the ship 12 prefabricated buildings for Midway, and 12 for Wake. We loaded - for each base - two diesel engines to generate electricity; two windmills to pump water up and get water pressure; a Caterpillar tractor with interchangeable bulldozer blade and crane (Seabees later made great use of these); 4,000 gallon tanks for both aviation gas and water. We were supposed to load 5,000 fifty-gallon drums of aviation gas, but when they’d loaded 1,600 the loaders went on strike. The North Haven had to pick up more gas at Manila and drop it off on its return trip. On the deck we loaded two 38-foot power launches, one for Midway and one for Wake, and a 26-foot launch for Guam, intended for air-sea rescue, and seven barges to tow the cargo ashore.

SS North Haven at anchor. Photo: Bert Voortmeyer, courtesy of Carol Nickisher.

We had nearly 80 construction workers. Some reports say they were mostly college boys. But except for a few of us, they were all professional construction workers: carpenters, plumbers, electricians. Some had worked on the Boulder Dam. We also carried the 12 Pan Am employees who would man Midway, and the 12 who would man Wake. We had two Navy observers aboard, and a journalist, Junius Wood.

In Honolulu we dropped the radio equipment at our base at Pearl City, across from Pearl Harbor, with our Station Manager, J. Parker Van Zandt. The Navy had sent a survey ship with a seaplane to Wake, which took pictures that showed a break in the coral reef that surrounded Wake, so the ship could land the cargo on the shore. The pictures also showed that many coral heads had built up in the lagoon. We needed six feet of water to land an M-130, so we took on a ton of dynamite and picked up a powder man at Honolulu. We also took on Bill Mullahey, who was brought up in Hawaii, educated at Columbia, and whose father worked for the cable company. Bill was another of us “college boys.”

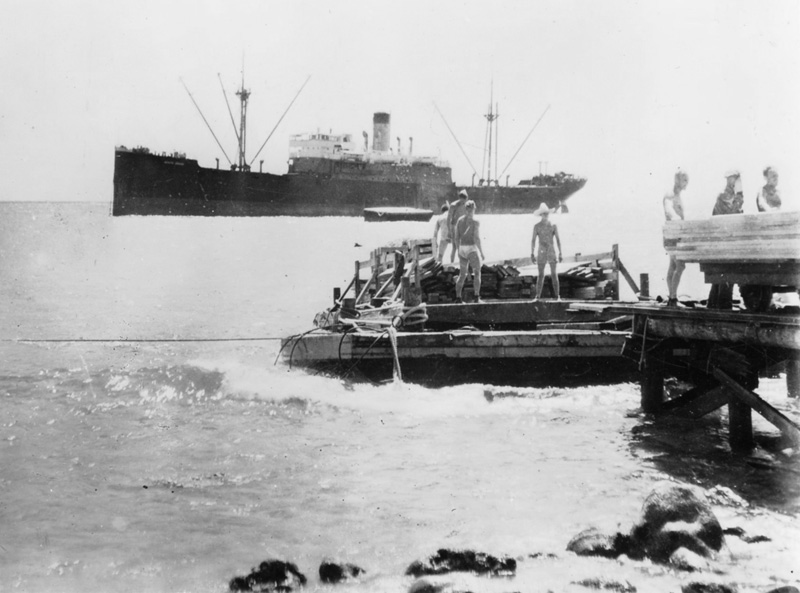

At Midway we had to unload in the open sea. It was hairy. We loaded the cargo onto the barges, and the power launches towed them four or five miles through the reef to the beach. I watched one barge slide down a swell sideways. Strangely, we didn’t lose a thing. One sailor injured his hand in the unloading, but we also had a doctor aboard. When we got to the shore, we loaded the cargo onto 4x20-foot sleds we’d designed, and the tractors towed them into place.

First we set up a temporary power plant; we had electricity the first night. Then we set up the food storage building, with a walk-in refrigerator and freezer, so the ship could leave. Then the construction workers started setting up the mess hall and kitchen; two crew buildings, one for base personnel and one for transiting aircrews (the hotel wasn’t built till 1936); the Station Office for operations, the radio operator, and dispatch; buildings for the radio transmitter and the Adcock direction finder; a repair shop for the chief mechanic; the windmills to pump water, and the station manager’s quarters. We also buried the 4,000 tanks for gas and water, though not deeply.

The North Haven waited while all the construction workers unloaded the cargo and the food. Then we picked up 46 construction workers, leaving 23 to finish the base at Midway, and sailed for Wake.

SS North Haven unloading at Wilkes Island, Wake Atoll, Smithsonian Nation Air & Space Museum.

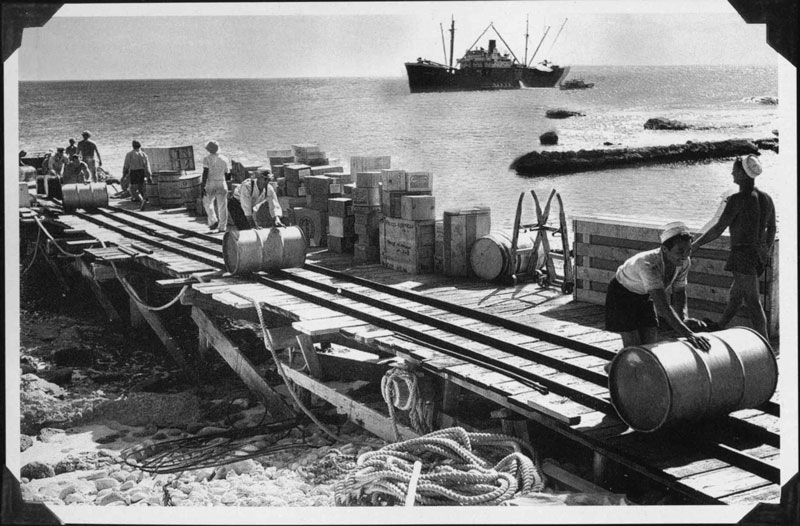

Activity at the Wake wharf, North Haven in distance. Kennler collection, courtesy of Jon Krupnick.

Wake is made up of three islands. It’s true it was uninhabited - except for birds. We had to wear hats. We’d planned to put the station on Wilkes Island, which is open to the sea, but the survey team found it was too low in the water. So was Wake Island. But Peale Island, on the far side of the lagoon, was okay. We unloaded the cargo into a storage yard on Wilkes Island, then built a 50- yard railroad to the lagoon (somebody by inspiration had brought light-gauge railroad track). We put the small launch on a barge and, with the help of the tractor, we shoved it across the knee-deep channel between Wake and Wilkes. The launch towed the barges of cargo across the lagoon to Peale Island, where we did the same song and dance as at Midway. Wake depended on rainfall for water, so we rigged canvases on the roofs, drained them into underground tanks, then pumped the water up with the windmills.

We had to clear a six-foot deep channel through the coral heads in the Wake lagoon for the M-130 to land. So we hung a length of a light-gauge railroad track six feet deep under a barge, and a launch towed the barge back and forth across the lagoon. When the track hit coral, it shook the barge, wakened the guy sleeping on it, and he threw a cork buoy with an anchor to mark the spot.

Pan Am Historical Foundation photo.

Then Bill Mullahey and I, in a rowboat, rowed out to the buoys. Bill put on goggles he’d made out of bamboo, took a bamboo spear, and dove down and inspected the coral head. The spear was in case he saw any fish that looked good for dinner while he was inspecting. The snorkel had not been in- vented; he just held his breath. Bill surfaced and said, give me six or eight sticks of dynamite, dove back down and tied them to the coral. He resurfaced. I rowed us upwind as far as we could go, and he pressed a magneto button and blew up the coral. We rowed back, picked up the fish the blast had killed, and brought them back for dinner. We did this till we cleared a pie-shaped landing area with the point near the dock. We marked the area with empty 50-gallon diesel drums. We’d built a 400-foot dock, using my 35-foot antenna masts as stringers, and attached the barge to the end of it. The barge now had a more dignified name: it became the landing float.

The SS North Haven sailed on to Guam and Manila to deliver the radio equipment, leaving us and the construction party at Wake. It had to find a launch at Guam; we kept Guam’s launch at Wake, figuring that the navy at Guam had boats.

Every day the wind blew from the southeast. I recorded it. The first day it blew from the southwest was when Captain R.O.D. Sullivan and co-pilot Jack Tilton (later Pacific Division Operations manager) flew an S-42 in on the survey flight. He discussed the crosswind landing colorfully.

The first China Clipper arrived in November, bringing us turkey for Thanksgiving, and continued to Manila. East- bound on its way back, it picked up seven of us at Wake, another three or four at Midway, and took us to Honolulu, where we got on a ship to San Francisco. The expedition was over. The China Clipper had crossed the Pacific.

Air service to Asia had begun.

And it started 60 years ago this March."

-- John Borger (Originally printed in the PAHF Clipper Newsletter, Spring 1995)

Rough seas and the SS North Haven (PAHF/Fulton Film collection).