Pan American Airways' Mission to China, Part 1

by Eric H. Hobson PhD

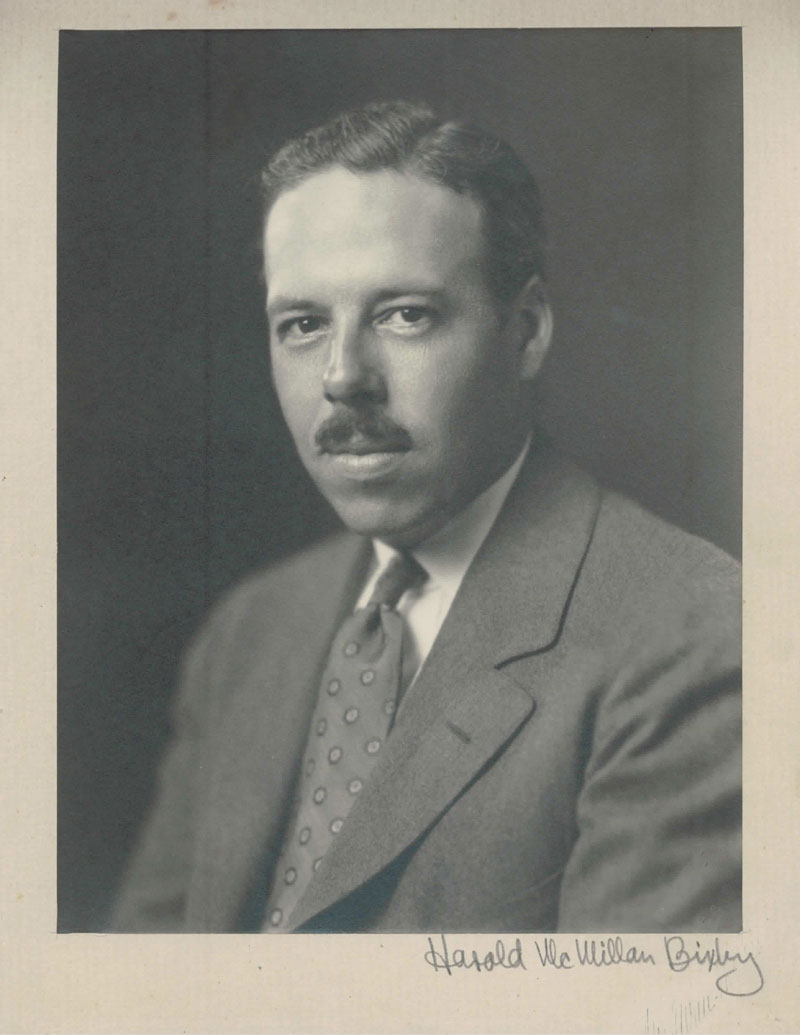

Harold M. Bixby’s Photo on Pilot License, 1929 (Courtesy Bixby Family Collection).

Pan American Airways executive Harold M. Bixby came to Shanghai, China, by way of St. Louis, Missouri’s well-heeled Central West End where he was born and had lived his entire life. By the time he joined Pan Am in January 1933, Bixby was one of St. Louis’ prominent citizens: Vice President, State National Bank of St. Louis; past President the Chamber of Commerce; aviation entrepreneur (St. Louis Aviation Company & Transcontinental Air Transport); and, one of eight St. Louis businessmen to finance Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo trans-Atlantic flight. Harold Bixby gave Lindbergh’s airplane its iconic name, The Spirit of St. Louis.

Harold Bixby standing behind Lindbergh Feb 13 1928 (Courtesy Bixby Family Collection).

In “The Spirit of St. Louis”, his 1953 account of the transatlantic flight, Lindbergh described Harold as “a man you like right away – smiling and full of humor.” Bixby’s engaging personality did not signal a lack of seriousness, however. “His penetrating brown eyes size you up,” wrote Lindbergh, “and warn you that you’d better pass inspection.” Continuing this character assessment, “You know you can depend on Harold Bixby.” Yet, added Lindbergh, “if he can’t depend on you he won’t be around you very long.”

By late 1932, forty-two-year-old Bixby wanted a career change. After graduating Amherst College in 1913, Harold entered banking at his father’s direction and was a success. His heart was with aviation, however, attached first to balloons, for which he trained during World War I, followed by airplanes (he earned his private pilot’s license in June 1929). Now, following the October 1929 global financial crash, and having promised to personally repay $60,000 to investors in a failed St. Louis sporting complex (although not obligated to do so) Harold was listening more attentively to his close friend “Slim” Lindbergh who had tried for years to convince Harold to finish the transition begun in 1928-29 from banking to commercial aviation. Lindbergh was adamant that Harold’s true place was with aviation.

Bixby (r) with A.B. Lambert at Lambert Field in 1931 (Courtesy Bixby Family Collection).

In the five years since making it’s first mail run on October 19, 1927, PAA proved that long-haul commercial air routes spanning the Americas were technically viable, commercially profitable, and, for the most part, quite safe if operated within exacting standards. But, as the company pushed to move mail and people via airplanes across the globe’s two great oceans, the Atlantic and Pacific, these proofs were not certain.

Likewise, PAA President Juan Trippe could not extend the company across the globe by adhering to his preferred hermetic management mode wherein he passed information to others (including his Board of Directors) in drips on a Trippe-determined need-to-know basis. Juan Trippe recognized that he had to find a trusted, discrete, and adaptable proxy on the corporation’s global fringes, particularly along the Pacific Rim. Given the complexities involved in PAA’s transpacific expansion plans, Trippe needed a diplomat/tactician as much as a lackey/surrogate; yet, he also needed a salesman, someone who envisioned and believed in global aviation as inevitable, and could describe it with missionary zeal, albeit, without huckster’s trappings. Charles Lindbergh, PAA’s Technical Advisor, told Trippe that the grand puzzle’s missing piece was Harold Bixby.

Harold was, Lindbergh told Trippe, incorruptible, with twenty years of executive experience, particularly along the lines needed to negotiate complex contracts in fluid settings, able to parse out creative solutions to otherwise intractable problems, and possessing an unvarnished awareness of complex American corporate structures and their financing, including commercial aviation companies. Additionally, Bixby’s experience as president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce had honed his tact and social skills, as his hands-on management of many aspects of Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight and its 1928-29 aftermath demonstrated. Charles assured Juan that Bixby could handle any situation that came his way, would remain calm and would focus always on PAA’s interests. Lindbergh believed Trippe would understand why he admired Bixby as he did as soon as he could arrange for the two men to meet.

Juan Trippe’s wife, Betty Stettinius Trippe, perpetuated the story that Juan was sold on Bixby as soon as Lindbergh introduced the two men late December 1932 in New York City. She noted in her diary that “Lindbergh introduced Bixby to Juan as one of the most honest individuals he had ever known and with that recommendation, Juan offered him the job to negotiate and manage the C.N.A.C. operation in China.” Bixby’s official PAA start date was January 15, 1933 and Trippe lost no time putting Harold to work. Bixby left San Francisco for Shanghai two weeks later for what both men thought (naively, as it turned out) might be a three-month project.

Harold’s assignment was complex. PAA sent him to a country he had never visited, to sell a service for which the technology to deliver it did not exist fully (1), and, to do so without his family (wife Elizabeth “Debby” and daughters Elizabeth, Frances, Hebe and Catherine). That said, Harold knew his assignment’s goals: secure the contracts and landing rights PAA needed to move mail, freight, and passengers from the US west coast to and throughout the Orient, and negotiate the snarl of permissions required to enable the construction of facilities to support the far-flung operation. More important, he understood that his US-based business experience and skills were not enough to allow him to complete the task: he would need to listen and observe, learn a foreign culture and its business norms, cultivate alliances, and make friends who could be his mentors or partners.

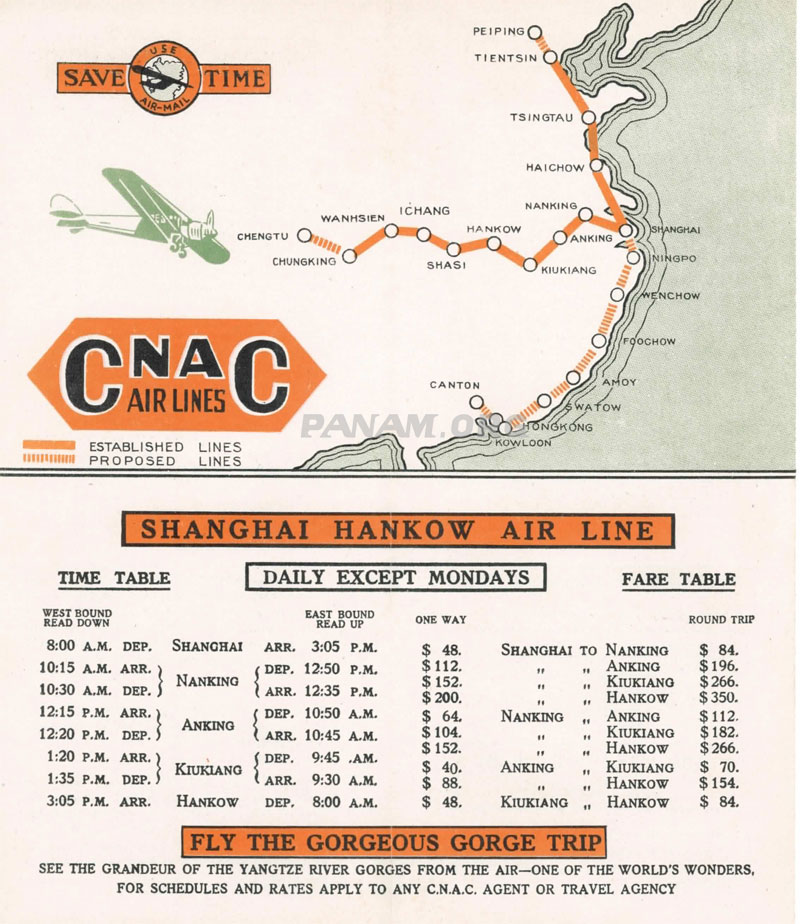

China National Aviation Corporation timetable cover, 1930 (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Juan Trippe placed unusual trust in Harold Bixby’s business acumen and executive skills from the outset, granting Harold signatory power to commit PAA to long-term and convoluted Asiatic arrangements at his discretion, albeit with one stipulation: no “grease.” Harold must carry out PAA-related business without resorting to bribery. As Betty Trippe recounted in her diary, “In China, bribery, called cumshaw, is usual. If not enough is given or too much accepted, the Chinese lose face. Pan Am has never given bribes anywhere, so when approached in China, Bixby was instructed not to comply with the custom.” (2)

Harold Bixby arrived Shanghai on February 11, 1933 and got to work on Trippe’s first goal, accessing China’s aviation market. The straight-forward plan was to persuade the Chinese Government to grant PAA landing rights and exclusive rights to carry airmail east to San Francisco (and points between). Two hurdles doomed this approach, however. First, China feared foreign incursion into its markets, which, given its history with Europe and Japan in the late-eighteenth, nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, made sense. Second, due to the Nine Powers Treaty of 1922, if China granted commercial access (e.g., domestic landing rights) to one of the “most favored nations” (Great Brittan, United States of America, Belgium, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal and Japan) it must allow them all in, including its regional nemesis, Japan. The landing rights effort was a long-shot, at best, but Bixby began on that front nonetheless. He soon conceded that the Chinese would never agree to an arrangement that opened China to more Japanese encroachment than already happening.

Bixby’s second option was to replicate the foreign-access model PAA had honed in Central and South America: acquire a national airline, either whole or in part, and, as a result of that purchase become a domestic, not a foreign, carrier. Unknown to the Chinese Government, PAA was negotiating stateside with Curtiss-Wright Corporation to buy its money-losing stake in China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC ownership was split 55/45 percent between China’s government and Chinese Airways Federal, a Curtiss-Wright shell company, and neither partner could sell its CNAC stock without the other’s permission). To determine a bid price, Harold Bixby investigated CNAC’s Shanghai offices, fleet, and maintenance facilities; he also assessed the airline’s operations, routes, personnel, financial position, and growth potential. With that information, Harold gave Trippe a low-ball bid: $181,385.

China National Aviation baggage sticker (Courtesy Don Thomas Collection).

Curtiss-Wright Corporation sold Intercontinental Aviation Corporation on April 1, 1933 to Pan American Airways. The transaction shifted International Aviation Corporation’s one asset, Chinese Airways Federal, to PAA. And, in keeping with the realities of corporate shell companies, Chinese Airways Federal brought to PAA a limited portfolio of assets: a small hanger at Shanghai’s Lungwha airport, and it’s 45% of CNAC stock. That CNAC minority stake was the deal’s core from the start, even if, by CNAC articles of incorporation, not a single share of CNAC stock could be sold without mutual agreement between Curtiss-Wright Corporation and the Chinese Government.

This sale infuriated the Chinese Government because it seemed a clear breech of CNAC’s charter. In China’s Wings, aviation historian Gregory Crouch points out that the sale “was a legally dubious transaction, but,” based on Bixby’s reconnaissance and on close assessment of CNAC’s articles of incorporation, “Pan American did wiggle in without violating the letter of the contract.”

Although the optics were ugly, Crouch points out that at the end of the transaction, “Pan Am didn’t actually buy CNAC and Curtiss-Wright didn’t actually sell it.” On April 1, 1933, each CNAC stock share remained with its prior owners (the Chinese Government or Chinese Federal Airways). Yet, PAA now owned Chinese Federal Airways.

The sale went though and PAA became CNAC’s minority partner. Transnational relations were strained and Harold Bixby, the new CNAC Board minority representative, faced a new challenge. He must gain his new Chinese business partners’ trust because PAA could not work toward it’s transpacific air-service goal without the Chinese Government.

But establishing a healthy partnership would not be easy. The Chinese needed to see clear signals of PAA’s long-term commitment if Harold was to establish a bi-lateral starting point for improving CNAC inter-ownership relations; mending fences with the many governmental agencies involved in China’s domestic mail service and transportation sector was equally vital. The more Bixby understood about Chinese culture, it became clear that each CNAC Board Member needed irrefutable proof that as PAA’s representative, he (and, thus, all the Americans involved) was committed to China.

Photo of Harold Bixby’s Family photo 1935-36. (Courtesy of Bixby Family Collection).

Chinese officials had asked Bixby repeatedly about his family and why they were not with him. He now understood that his CNAC partners and the many government officials with whom he needed to work, saw Debby and the girls’ absence as signifying his and PAA’s lack of respect and of long-term commitment. Debby and the girls must join him in China; and, because Harold wanted his family with him in China, too, this was a cross-cultural misread that he was happy to fix. But first, he needed a reason to remain in China, and that reason was in jeopardy: if the Shanghai to Canton air-mail route did not move from paper possibility to a revenue-generating reality, he and PAA were leaving Asia. Without that route, PAA’s transpacific aspirations could not materialize.

Early CNAC Route Map (Pan Am Historical Foundation).

The April 1, 1933 CNAC acquisition gave PAA access, albeit indirect, into China. However, it needed CNAC’s three mail concessions (Route No. 1: Shanghai to Chengtu; Route No. 2: Shanghai to Peiping; and Route No. 3: Shanghai to Canton) in full operation for the company to recoup any of the massive investments required to modernize CNAC. Yet CNAC’s majority owners ignored Route No. 3 for two valid business reasons. First, the Chinese members of CNAC’s Board of Directors stated that the nearly bankrupt company hadn’t cash to survey or to develop a one-thousand-mile coastal route, or to build aviation infrastructure to support the route. The Chinese Government prioritized the two inland mail routes (Route No. 1 & 2) that linked major provincial cities, and, thus, produced revenue and military value; from their perspective, five-day southbound mail traffic between Shanghai and Canton using proven steamships met Chinese Government and domestic/foreign business needs. If hasty Americans insisted on one-to-two-day air-mail service, they could carry the full cost. The Chinese would not budge on this point.

Time was running out for Bixby and PAA on their San Francisco-to-Shanghai transpacific project. To get mail (or passengers) to Shanghai, the Route No. 3 concession had to be locked down. However, CNAC’s original option on the route required that CNAC deliver mail between the two cities by July 8, 1933, after which the option expired. Although the route had not been surveyed, and no intermediate fueling/emergency bases existed, Route No. 3 was key to PAA’s transpacific aspirations because the obvious eastern end to its planned transpacific route was Shanghai: no other Pacific-Rim city but Manila was as economically powerful, or as internationally connected.

To complicate matters, China’s Ministry of Communications would not finalize contract specifics. Bixby sensed that the Ministry would dicker and delay until the concession expired on July 8. Then, on July 9, it could award the contract to a Chinese owned company, or renegotiate the contract on terms less favorable to CNAC’s minority owner, PAA (even if the Government was CNAC’s majority shareholder!).

Refueling Pan Am (Pacific American) Sikorsky S-38 at Wenchow in the first of two Sikorsky S-38’s assembled from PAA’s Caribbean service, July 3, 1933 (CourtesyBixby Family Collection).

Following Pan Am’s October 1927 quick-thinking precedent to secure its first international air-mail contract (the about-to-lapse Key West to Havana concession), Bixby flew from Shanghai to Canton on July 3, 1933 in one of two just-shipped and just-assembled Sikorsky S-38 amphibian aircraft transferred from PAA’s Caribbean service to modernize CNAC’s fleet. Arriving in Canton, Harold faced a new hurdle when the Chinese postal service refused to provide him with Shanghai-bound airmail needed to complete the contract. Undaunted, Harold convinced a Canton-based British postmaster to let him fly north with two sacks of regular Shanghai-bound mail. The plane landed at Shanghai’s Lungwha airport on July 8, 1933, the last day allowed by the original Route No. 3 contract.

With official documentation of mail delivery in one hand and the Route No. 3 contract in the other, Bixby entered the Ministry of Communications office and declared the contract executed. As Harold explained to Minister Wah, in rereading the contract with the eye to detail that he had developed as a banker, he noticed that the contract stated that “mail by air” (not “airmail”) had to be delivered by July 8, and thus, he had abided by the contract’s stipulations. Following side consultation with his aide, Minister Wah conceded the legality of Bixby’s move, and, as reported in Pan Am at War , laughed and said, “You win.” Still, Minister Wah, and the Chinese Government, believed that Bixby, and thus PAA, had pulled “a fast one,” again.

Footnotes:

(1) Although PAA had placed orders for transoceanic aircraft (Sikorsky S-42 & Martin M-130) in early 1932, the first S-42 would not roll off the assembly line until December 1933 and would not see scheduled service until August 1934. PAA would not receive its first M-130 until October 1935.

(2) Because Harold adhered to this order, Betty Trippe, wrote, “Some months later, Pan Am was asked by the Chinese Government to be its world-wide purchasing agent, as they knew that Pan Am could be trusted with the funds.”

Works Cited

Barrett, Benjamin C. The Spirit Behind the Spirit of St. Louis Harold M. Bixby. Troy Book Makers, 2019.

Bender, Marylin and Selig Altschul. The Chosen Instrument. Simon and Schuster, 1982.

Bixby, Debby. The H.M. Bixby in China 1934-1938. Self-published pamphlet, circa 1950.

Crouch, Gregory. China’s Wings. Bantam Books, 2012.

Lindbergh, Charles A. The Spirit of St. Louis. Scribner’s, 1953.

Trippe, Betty Stettinius. Pan Am’s First Lady: the diary of Betty Stettinius Trippe. Paladwr Press, 1996.

Vas, Mark Cotta and John H. Hill. Pan Am at War. Skyhorse Publishing, 2019.

Acknowledgement:

Thanks to Ben Barrett for publishing “The Spirit Behind the Spirit of Saint Louis, Harold M. Bixby” which compiles materials from his grandfather’s life, for answering a host of my questions, and for providing photos to enliven this article.

Read excerpts & purchase Ben Barrett's book now available at:

https://www.thespiritbehindthespiritofstlouis.com/

Related Articles: