Pan American Airways’ Mission to China; Part 2

Eric H. Hobson PhD

Sitting at his desk on the upper floor of the Shanghai Post Office Building on the famous Bund overlooking the Whangpoo River, Harold Bixby knew that regardless of how fast his Pan American Airways (PAA) colleagues in New York City wanted him to move forward on the company’s transpacific plans, haste was the last thing needed on the China end of the company’s far-flung endeavors. In July 1933 the most valuable gift Harold could give PAA’s Chinese partners was a cooling-off period.

Shanghai’s Bund, ca 1930s (Wikimedia Commons).

During his six-months as Pan American Airway’s Far Eastern Representative, Harold’s first two major moves had caused the Chinese members of the China National Aviation Company (CNAC) Board of Directors to lose face before he understood the necessity of face-saving in Chinese culture. Even now, two months after learning that they were no longer partners with the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, the CNAC Board (representing the Chinese Government’s 55 percent majority ownership of CNAC stock) was still adjusting to April 1’s shocking news: Pan American Airways was its new corporate partner.

PAA was known as a Caribbean-South America aviation powerhouse, and its sudden revelation as CNAC’s minority partner had not been anticipated. No CNAC board member, including William Bond, CNAC’s American Operations Director, had foreseen the corporate shell-company machinations through which PAA came to replace Curtiss-Wright as CNAC’s minority partner. Additionally, the CNAC Board was facing the reality that, following Harold Bixby’s second corporate improvisational move in two months, the company must now figure out how to run an airmail route that it’s majority share holder did not view as a corporate priority.

CNAC Shanghai Passenger Terminal exterior n.d (Pan Am Historical Foundation, John Johnson Collection).

Harold could see that remaining in Shanghai meant constant contact with these suspicious and bruised individuals. To mitigate that friction, Bixby decided to leave town…and country. After informing PAA’s New York City headquarters of his plans, Harold headed south to Hong Kong, Macao, and Manila to tackle other parts of his PAA Far Eastern Representative assignment.

In mid August 1933 (his eighth month in China) Harold organized a multi-stop multi-week aerial scouting trip down China’s southern coast and across the South China Sea to the Philippines. The goal was to identify and understand the pieces of the transpacific commercial aviation puzzle. If PAA was to achieve President Juan Trippe’s dream of global air service, the company had to get to work. In addition to the obvious challenge of getting aircraft from San Francisco, California to China in one piece with a revenue-generating load, complex infrastructure was needed along the flight path to make any route viable. There was much to learn about weather across the Pacific and atmospheric realities in the air above the open ocean. The company must have this information in hand to develop rational timelines toward launching and maintaining a revenue-producing transpacific air service.

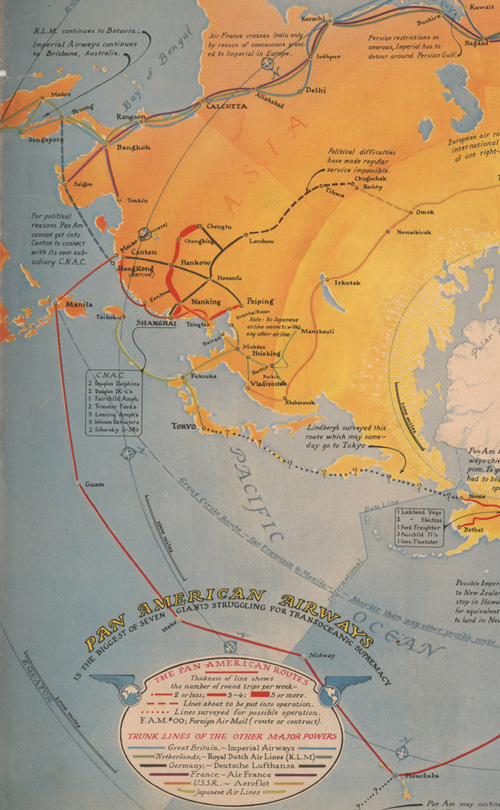

Geopolitical tensions forced PAA from its transpacific master plan for a northern route (via Alaska, Russia’s far-western territories, Japan, China) to a straight-west, island-hopping route -- Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, Philippines, China – along US controlled stops. Until late 1933, Russia would not allow an American airline to land on its soil as long as the US Government did not recognize Russia’s Communist Government. Japan was telegraphing regional expansionist intent that, to those sensitive to the region’s history, discouraged speculative investment in parts of the first route’s planned pathway. And, trumping all else was meteorological fact: weather along the northern Pacific route was best described as bad-to-terrible for most of the year.

A cartographic view of Pan Am’s and Harold Bixby’s world. Fortune Magazine, April 1936, by Richard Edes Harrison (Courtesy Library of Congress Cartographic Division).

Other tightly knotted obstacles blocked the project’s path: xenophobia, international competition, territorial sovereignty, treaty obligations, political self-interest, and economic protectionism. None of these would resolve quickly. Government and business leaders along the projected route needed to be convinced that transpacific air service was in their constituents’ best interests, as well as their own. It was for this context that Juan Trippe had selected Harold Bixby to serve as an aviation missionary, and Harold needed to spread the aviation “good news” to diverse audiences outside mainland China.

As PAA’s New York City brain trust studied the westward-island-hop option, the team posited a host of questions about which Harold could supply answers, particularly because Manila was the leading candidate for PAA’s Asiatic base of operations. From Manila, PAA South-Pacific routes could veer northwest to reach China, and, once demand for transpacific air service grew, expand into Southeast Asia.

Therefore, Pan Am needed to design a Philippines-to-China flight path, navigate the Philippine’s political landscape as it moved toward self-governance in 1935, and convince either England or Portugal to allow PAA to land at Hong Kong or Macao, their mainland China colonies. Financially, PAA must also secure mail concessions (US Postal, and any others) along the proposed route.

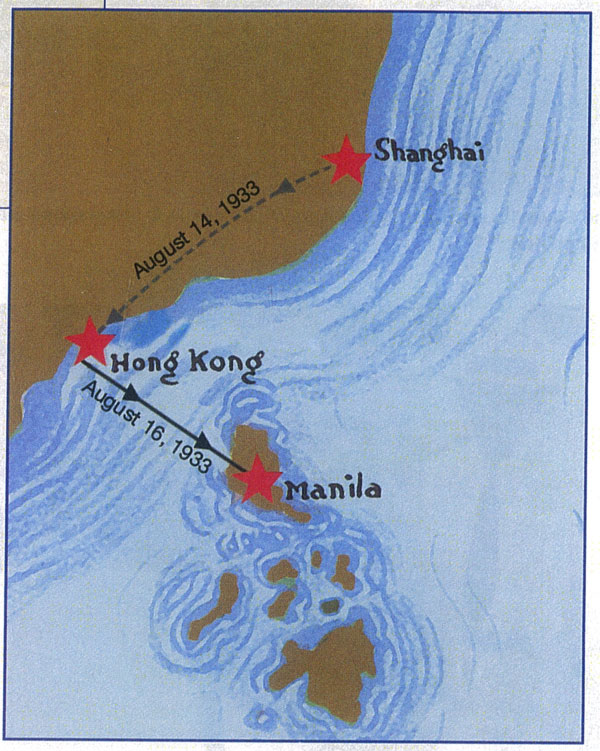

Map of Asia’s Coast (Courtesy Jon Krupnick collection).

Map of Asia’s Coast (Courtesy Jon Krupnick collection).

On Monday, Aug. 14, Bixby, pilot William S. Grooch and co-pilot/radio operator William Ehmer left Shanghai in a Sikorsky S-38 amphibian to scout a Shanghai to Manila route. They flew down the coast from Shanghai to Foochow to refuel – a critical stop along the Route No. 3 mail route, then continued to Hong Kong. There, according to an Associated Press reporter, they “conferred with E.D. Hester, American Trade Commissioner for the Philippines.”

On Wednesday morning, August 16, using the dead-reckoning skills he had developed early in his career, Grooch flew five hours southeast over the South China Sea to the northwest tip of Luzon Island (~450 miles), then turned south and landed at Lingayen Bay where they refueled, met the first of many reporters who wanted to be the first to report on this historic first commercial flight from China, and took off again for Manila two-hundred-fifty miles further down the island’s western coast. At 3:35pm Bill Grooch put the S-38 down on Manila Harbor in front of the Army and Navy Club where a crowd of dignitaries, reporters, and spectators had gathered to welcome the three men to the Philippines.

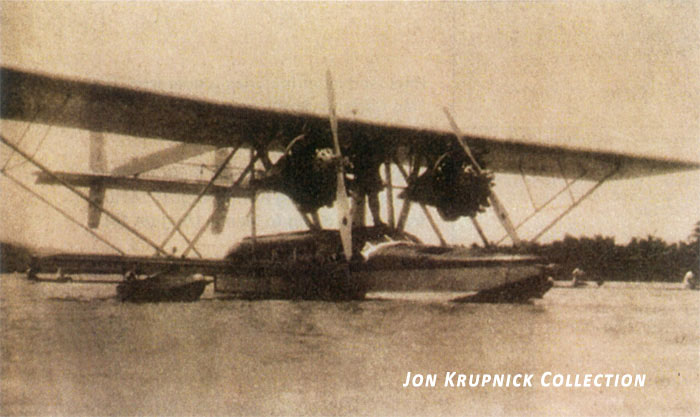

Pan Am (Pacific American Airways) S-38 survey plane, the first American plane to visit the Philippines (Courtesy Jon Krupnick collection).

![]()

The Sikorsky’s arrival in Manila was front-page news for the Thursday, August 17, 1933 issue of The Tribune (Manila). Readers learned that “The purpose of the present survey flight to Manila is to make a study of weather conditions and other physical aspects of the route between Hongkong and Manila, as well as to study the commercial possibilities of the line.” Dignitaries who stood at the Army and Navy Club’s dock waiting for Bixby, Grooch, and Ehmer to finish clearing customs included a cross section of Manila’s governmental and business leaders. Representing the U.S. Government was the Territorial Vice-Governor John Holliday and his wife, accompanied by the city’s Mayor Tomas Earnshaw. William Shaw and W.R. Bradford, of the Philippine Air Taxi company, and Major J.E.H. Stevenot, Vice President of the Philippine Long-Distance Telephone Co. were among the American expatriate business leaders whom Harold wanted to meet.

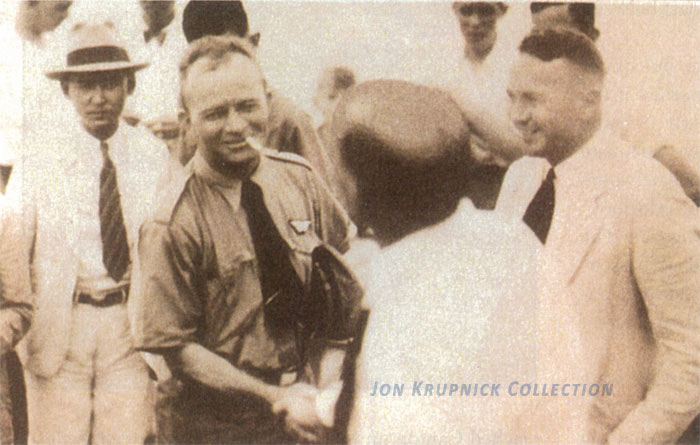

Grooch and Bixby (back to camera) were warmly greeted in Manila (Courtesy Jon Krupnick collection).

The Tribune readers were also given a summary of events and meetings these visitors were scheduled to attend. In addition to briefings with persons involved with Philippines’ aviation sector and with U.S. and Philippine officials, the three men were bombarded with invitations to dinner and other social gatherings. Businessman William J. Shaw got a jump on this front: he radioed his invitation to Bixby aboard the S-38 before it landed in Manila Harbor asking the three men to join his Saturday at the Wack Wack Golf and Country Club for a luncheon he wished to hold in their honor. Throughout their two weeks in Manila, Harold Bixby and his two PAA colleagues were the center of much attention and the source of much speculation.

Harold told reporters that the main obstacle standing in the way of Manila to Shanghai air service was the need to have intermediate fueling stations constructed along the entire route. He commended the professional work of the Philippine Weather Bureau, and suggested that PAA would not need to replicate that service as it looked to establish its Manila ground operations. When pressed on the issue of a start date for Shanghai to Manila airmail service, however, Harold was more circumspect, citing the many decisions that lay before everyone involved in the project.

Manila’s business and political community found Bixby refreshing. Harold’s conservative banker’s training showed, and his meticulous attention to detail was appreciated. Unlike other entrepreneurs pitching grand schemes, he would not make promises. In his book, Winged Highway (1938) Pilot Bill Grooch recounted one particularly important meeting between Bixby and Philippine power-broker Manuel Quezon:

When Bixby explained our plans, Quezon seemed genuinely interested.“Do you really plan to fly the Pacific,” he asked, “or is that just newspaper talk?”

“The planes are being constructed,” Bixby answered. “They’ll be coming through to China within two years.”

Quezon smiled skeptically. “The Pacific is a large ocean, senor.”

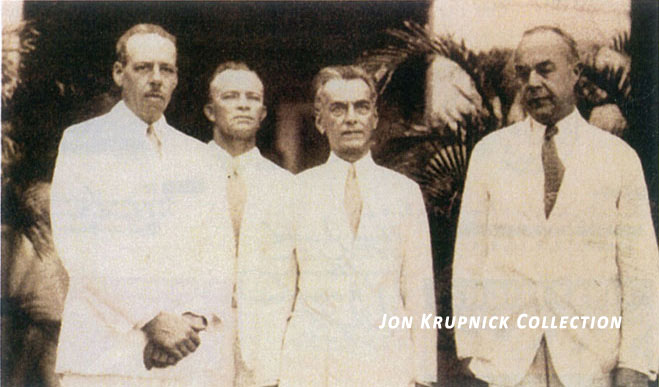

Bixby, Grooch, and Senator Quezon in Manila (Courtesy Jon Krupnick collection).

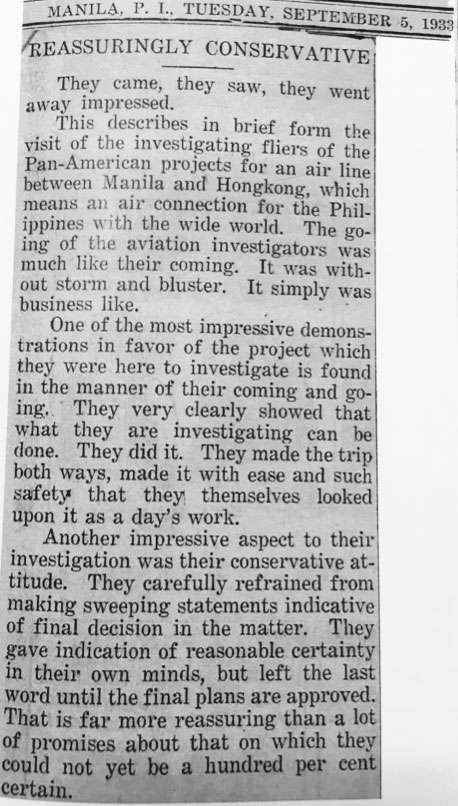

Summarizing the Pan Am team’s Manila to Hong Kong scouting mission, a Manila Bulletin editorial writer observed, “They came, they saw, they went away impressed… It simply was business like.”

By the time Bixby returned to Shanghai September 4, he and his crew had scouted the length of the Philippines by air. They looked for refueling sites along Luzon’s northwest coast, and investigated port options in and around Manila. Additionally, at the request of PAA’s New York City transpacific service planning team, they also looked south to the harbors at Iloilo midway down the chain and Samboanga at the country’s southwest tip; once PAA got to Manila, President Trippe would push for routes to Singapore, Saigon, and other Asian cities.

The PAA S-38 survey flight arrives back at Shanghai 1933 (Courtesy Nancy Allison Wright & the Allison Family Collection)

After nearly three weeks of traveling, and after forty-five hours in the Sikorsky S-38, Bixby, Grooch, and Ehmer returned to Shanghai Monday afternoon, September 4, 1933. Each man needed to stretch his legs after climbing out of the aircraft and onto the Lungwha Aerodrome’s dirt landing strip. However, reporters and cameramen from Shanghai’s dailies demanded interviews and pictures. Harold obliged, and The China Press morning-edition story stated, “The way is now paved for the early inauguration of the Shanghai-Manila airline following the safe return here yesterday afternoon of the large twin-motored Sikorsky amphibian airplane on the completion of its survey flight to Manila and back.” The story was illustrated with a photo of Bixby, Grooch, Ehmer (and another CNAC pilot, George Rummil) standing in front of the S-38, which the writer labeled their “trail-blazing machine.”

The Manila Bulletin report, "Reassuringly Conservative" September 5, 1933

The Manila Bulletin report, "Reassuringly Conservative" September 5, 1933

Although Harold had secured the CNAC-controlled Route No. 3 contract in early July, 1933, it could not be put into service because CNAC board chairman K.C. Huang refused to authorize CNAC resources to develop the route. Bixby and Huang discussed the issue throughout July, August and September, with both men aware throughout the long negotiations that Mr. Huang held the stronger hand. As Greg Crouch writes in China’s Wings, “Pan Am was in a hurry, China was not, and CNAC chairman K.C. Huang knew it. Huang held out for his terms.”

Finally, at the start of October, 1933 Bixby and Huang agreed to a plan Harold crafted that met both men’s needs to have their constituents’ positions validated. Surprisingly, after Huang’s experience with Curtiss-Wright Corporation’s shell companies, he and Bixby returned to that corporate slight of hand to solve their seemingly intractable Route No. 3 problem. PAA incorporated a wholly-owned subsidiary, Pacific American Airways, and in turn, CNAC hired Pacific American Airways to run Route No.3 as a charter operation.

Pacific American Airways, was Pan Am owned, staffed, managed, and funded, and Harold Bixby was its president. Pan Am provided the aircraft and personnel on the route (aircraft sported CNAC livery with “PAA” stenciled on each fuselage in small print, in English, not Chinese characters) and invested $250,000 to build out the maintenance, meteorological, and radio infrastructure required to make the Shanghai to Canton run as safe and efficient as any leg in PAA’s global system. CNAC took a cut on all Route No.3 revenue, domestic or international. As Greg Crouch notes, “For China, it was a superb bargain. With no obligations and no capital investment, Huang secured Pan Am’s commitment to develop a new Chinese airline, virtually guaranteeing CNAC a profit against negligible risk.” “Pan Am also got what it wanted, however,” continues Crouch, “the ability to construct an airline across the Pacific from San Francisco to Shanghai.”

Ten months into his China posting, Bixby received a boost from his immediate Pan Am boss, Stokely Morgan, who wrote in a confidential letter, dated October 3, 1933, “the reports coming from people who have been in close contact with you recently, have been overwhelmingly favorable.” Morgan continued by telling Harold that all of Pan Am’s executive team, including Juan Trippe, agreed that Bixby was invaluable.

To put it briefly, … if we had search the world over for just the right person to handle the difficult and complicated job which was laid upon your shoulders, it would have been impossible to find anybody either better suited for it by general ability and temperament, or who could have handled the situation as it developed anywhere near as well as you have. We have been informed, and have every reason to believe, that your standing with our Chinese associates and with Government officials is not only of the best, but it is marked by sentiments which come very close to real affection for you on their part.

Harold, too, was upbeat. Route No. 3 was scheduled to begin twice-weekly mail service from Shanghai to Canton on October 24, using two Sikorsky S-38 amphibians (and nine PAA employees) transferred from PAA’s Caribbean Division. Passenger service would follow on November 24 if all went smoothly during the route’s shake-down period.

With these arrangements in place, Harold boarded the SS President McKinley Tuesday, October 17 to return to Manila. There was still a host of details to negotiate on that end of the Shanghai to Manila route. A September 25, 1933, newspaper article iterated one major hang up: as the Philippines moved toward self-rule many aspects of its business were in flux as its Legislature worked to assert its authority. “Due to an impending change of government policy on the granting of air franchises,” the article noted, “no assurance can be given that the 25-year franchise requested by the Pan-American Airways to operate a Hongkong-Manila air route can be granted immediately.” With James Ross, Jr., PAA’s local lawyer, in tow, Harold met with the country’s power brokers, particularly Senator Elpidio Quirino, leader of the Philippine Senate, and Manuel Quezon, the leading candidate to become the country’s first elected president. Bixby would become a familiar face in Manila’s corridors of power over the next four years.

Seven weeks after getting Morgan’s letter which contained a strong vote of corporate confidence in Harold, however, he and CNAC faced grim news. After having watched Route No. 3’s first passenger-carrying Sikorsky S-38 leave Shanghai at dawn on November 24, 1933 carrying seven passengers and two crew, he learned that radio contact with the flight was lost. At 2 p.m. Harold received a telegram stating that the plane had crashed in heavy fog at Chusan Island, less than one-hundred miles into its one-thousand-mile route. Thankfully, the first reports that all aboard were dead proved incorrect, and although most passengers were injured, all survived.

The accident rattled Bixby, as evidenced by a letter to his wife two days later. “Debs” he wrote, “it was all so awful seeing the passengers off at 6 a.m. and then the worry – the news at 2 p.m. that all nine were dead and the hours of worry afterward. Its all a terrible nightmare now which I want to forget if I can.” He added, “The whole thing is just rotten luck…but on the first trip with passengers it just seems too unfair for words.”

As 1933 ended, and after twelve months on the job, Harold Bixby could report three accomplishments: PAA was part of China’s aviation market through it’s minority stake in CNAC; CNAC had the Shanghai to Canton Route No. 3 locked up, even if regularly scheduled service was just beginning; and, PAA controlled all operational aspects of the much-coveted Route No. 3 through its subsidiary, Pacific American Airways.

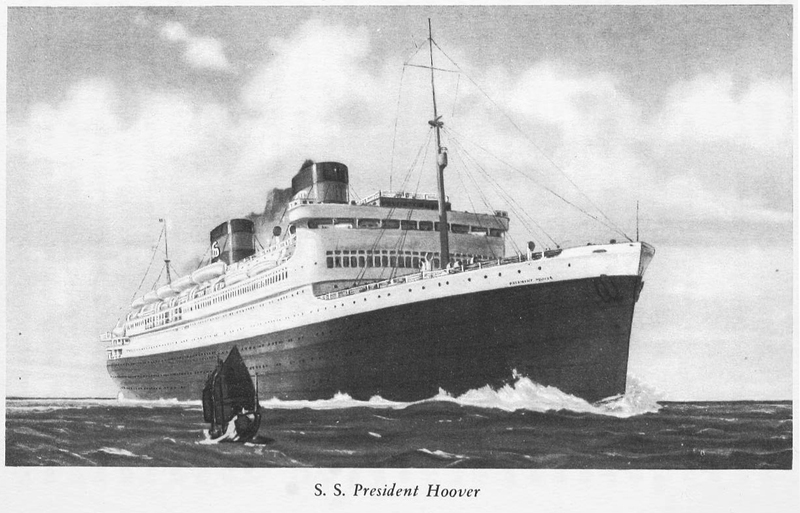

The SS President Hoover: Harold’s Bixby's ride home after a job well done. (Wikimedia Commons).

Work remained before PAA opened its San Francisco to Shanghai transpacific service, and it would prove contentious, complicated, and slow. However, Harold held a first-class ticket in his name for the SS. President Hoover’s January 2, 1934 eastbound sailing. Juan Trippe had called him home for consultation and next-stage planning; he would work on the transpacific project out of PAA’s New York City office for the next eight months. Most important, he would be with Debby and his daughters for the first time in a year.

Works Cited

Barrett, Benjamin C. The Spirit Behind the Spirit of St. Louis Harold M. Bixby. Troy Book Makers, 2019.

Crouch, Gregory. China’s Wings. Bantam Books, 2012.

Grooch, William Stephen. Winged Highway. Longman’s, Green & Co., 1938.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Jon Krupnick, Nancy Allison Wright, John Johnson, Library of Congress, and Pan Am Historical Foundation for photos and footage for this article.

Thanks to Ben Barrett for publishing The Spirit Behind the Spirit of Saint Louis, Harold M. Bixby which compiles materials from his grandfather’s life, and for his assistance in answering a host of my questions.

Read excerpts & purchase Ben Barrett's book now available at:

https://www.thespiritbehindthespiritofstlouis.com/