WHEN PAN AM'S CLIPPERS WERE TARGETED IN BERMUDA

War comes to Bermuda – after a fashion

On January 18th, 1940, Capt. Charles Lorber set Pan Am’s majestic Boeing 314 “American Clipper” down in Bermuda’s Great Sound to dock at the Darrell’s Island seaplane base after a flight from Baltimore, on her normal transatlantic run. Bermuda, a British colony, notwithstanding the onset of war in Europe just over three months before, presented its usual pleasing picture of calm from the air, its tranquil turquoise waters set off by green hills and whitewashed buildings (although the passengers couldn’t appreciate the view until they got off the plane, as new British wartime restrictions demanded that the clipper’s shades be drawn during the approach and landing).

Despite the onset of World War Two in Europe the previous September, there had been little disturbance in the transatlantic flights, other than the immediate curtailing of European ports of call. The clippers continued to fly to neutral Lisbon, Portugal. Foynes, Ireland was no longer served after October, due to its proximity to the war zone. The remaining transatlantic connection became vital – German U-boats had started their campaign of terror on the high seas, and were sinking ships of both enemy belligerent and neutral countries. Most of the airmail coming and going from Europe and points beyond too, was funneled through Lisbon, and the air route to Lisbon went through Bermuda, and Horta in the Portuguese Azores. In a world that was teetering on the verge of total global conflict, with restrictions on travel and every other strategic resource, the air connection across the Atlantic became critical. Peaceful Bermuda was a focal point for international connections in war.

In January 1940, the United States itself was still neutral – it would be almost another two years until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Official policy of the American government was to observe, and expect other nations to observe, the Hague Convention of 1907, which was very clear about non-interference with international mail during wartime. There already had been some issues arising from British interdiction and censorship of Europe-bound mails carried on US flag ocean-going vessels, and US Secretary of State Cordell Hull was known to be considering an official protest to Great Britain.

Americans’ popular views about Britain’s international situation were not overwhelmingly supportive in early 1940. Many people wanted no part of any conflict in Europe – the economic challenges of the Depression were still very real. Although invading Nazi (and Soviet) armies had overrun Poland in September 1939, the war had quickly gone quiescent, while Britain and France waited tensely for their turn – the period was called the “sitzkrieg.” The very real blitzkrieg attacks on Norway, Belgium, Denmark, Holland and France were still in the future. Non-intervention was a popular concept among Americans, although far from universal. There was even some real hostility among certain American business interests, who were becoming aware that Britain was attempting to restrict American exports – in particular tobacco – to any place where they might end up in German hands.

Economic Warfare

But the British were moving as fast as they could to a full-on war footing, and they were more than aware of the importance of hostile economic and other subterfuges that could be carried on via international correspondence, not to mention the passing of military information that could aid the enemy. They wanted to intercept securities that could be transmitted by mail that might fund enemy war efforts, as well as German news and propaganda that might reach and bolster “fifth columnists” who might undermine their own war efforts. Even just gauging morale as revealed in personal correspondence could be useful to the enemy. The British government knew that open warfare with Germany and her Axis partners was coming soon, and they were ready to act.

But it was a surprise indeed to Capt. Lorber when, after his passengers debarked from the clipper that January day in Bermuda, a crew of British mail censors stepped aboard.

According to an account published the following month in the New York Times, the encounter went like this, when the head censor addressed Lorber:

“Captain Lorber, we are going to remove your mail.”

Lorber: “Why?”

“Orders from the home government for censorship.”

“You can’t do that. This is a United States vessel.”

“Yes, we can,” he was told. “You are in Bermuda waters.”

“The only person I will allow on this aircraft is the port doctor, according to custom. I’ll do everything in my power to prevent the removal of that mail!” And he ordered the censors off the clipper.

With that, as the account went, the censorship crew left the plane. Back on the dock, the chief censor blew a whistle, and a launch filled with British marines, armed with rifles with fixed bayonets put out from the nearby shore. They came aboard the clipper, following Capt. Lorber up the stairway to the Boeing’s flight deck above, where the clipper’s load of over two tons of mail sat in bags, which the marines began to remove.

Lorber’s protest was noted, and ignored, and half of the mail – reportedly 112 bags - was removed from the clipper to be opened, reviewed, and censored or confiscated as deemed necessary. A few days later a brief news item surfaced that said, among many other things, three letters to Adolf Hitler had been found by the censors, without comment as to what they contained. Also found, it was claimed, were securities and large money transfers and even packages of diamonds, all bound for German destinations.

About the same time, there were other reports of likely British censorship of mail carried by Pan Am planes to Colombia, during a stop in Jamaica.

“A Hell of a Note”

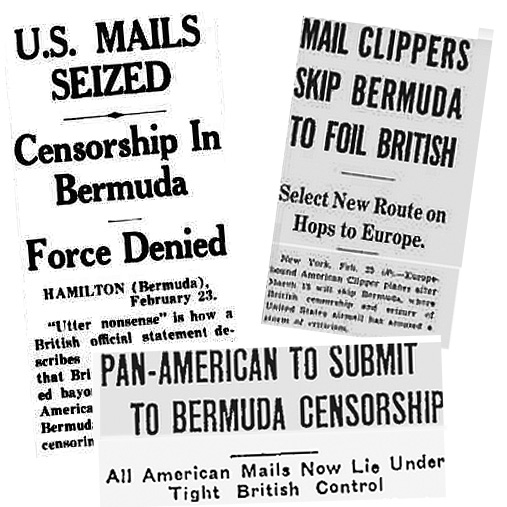

It took about a month for some of the political ramifications to reach a head in the US. Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota, a prominent “isolationist,” was one of the outspoken critics of what was by now a much-refuted claim of an armed “invasion” of the clipper. The British ambassador had made a statement that no armed force was used to remove the US mail. Senator Harry Truman called the mail’s forcible removal “a hell of a note.” Senator Key Pittman of Nevada, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, called the British action “excessive, and very foolish.”

To add confusion to the story, the British Ministry of Economic Warfare issued a statement of regret that armed force had been used to remove the mail, and made assurances that it would never happen again.

A few days later, on February 24th, another report surfaced, from a “corroborating witness,” also reported in the New York Times, to confirm that British soldiers indeed had been called upon to remove the mail, although the unidentified witness declined to say how they were armed. At the same time, a long statement was issued in Bermuda by the still-anonymous “chief censor” who explained that the scheme to remove the mail had been made in secret weeks earlier. The idea was to impress upon an un-forewarned Pan American captain that he was up against a “force majeure” – resistance would be futile, in other words. The statement again refuted the claim of armed force having been used: It was just a group of unarmed special constables and one nervous bureaucrat who had confronted the clipper’s skipper.

Pan Am, for its part, refused to make any sort of comment.

America Retaliates

Towards the end of February, Pan Am announced that clipper flights to and from Europe would soon be skipping the stop at Bermuda, because improved weather reporting was available thanks to the posting of US Coast Guard ships along the route. The 2,300-mile hop from the Azores to America’s east coast ports was workable, although factoring for extra fuel reserves for the longer flight would cut down payload.

And so it was an unexpected opportunity for the British censors when the Atlantic Clipper, Capt. Culbertson commanding, was forced by unfavorable winds to stop in Bermuda on March 28th. No confrontation this time. Geniality prevailed, as did British censorship, and so about 80,000 letters were carried off of the clipper to be examined. Apparently the unexpected arrival of the clipper made for a hasty return to duty for a number of foreign language experts who had been dismissed from their censoring work when the clippers started bypassing Bermuda.

The scenario was repeated in May, when the Atlantic Clipper was again forced to land in Bermuda, having to turn around on an eastbound flight. By this time, the political complexion of Europe was undergoing a radical transformation, due to lightning German invasions of Western Europe. The invasion of private correspondence seemed less important now.

And it happened again in June, when the Dixie Clipper was forced to divert to Bermuda on a flight from Horta. The reporting of the incident was much more subdued now.

War Changes Everything

Eventually, the whole issue was made moot by the rush of events. By August, Pan Am resumed making stops in Bermuda, with no more qualms about censorship from the US government. It seems likely that, as with so many other aspects of national policy, Pan Am was working in harmony with the US government. Such was hinted at with the reporting of a meeting between Pan Am’s President Juan Trippe, and Sumner Welles, Under Secretary of State. Although Welles’ boss Cordell Hull affirmed the official “anti-censorship” stance of the US, the earlier sharp tone was very much muted.

Now it was obvious that the United States could, in this small way, come to the aid of an embattled Britain. The chance for British censors to dig into every load of mail and express passing through their genteel colony could materially support their blockade of Hitler’s Europe. It was very small potatoes compared to the damage being wrought on transatlantic convoys bringing vital supplies to Britain by German U-boats, but it helped.

Now it was obvious that the United States could, in this small way, come to the aid of an embattled Britain. The chance for British censors to dig into every load of mail and express passing through their genteel colony could materially support their blockade of Hitler’s Europe. It was very small potatoes compared to the damage being wrought on transatlantic convoys bringing vital supplies to Britain by German U-boats, but it helped.

In fact, America’s secret intelligence organizations – both the FBI and the OSS, had been working with a newly organized arm of Britain’s MI-6, the secret intelligence organization, known as British Security Coordination (BSC). The group, headed by William Stephenson, was working under cover of the British Passport Control Office in New York City’s Rockefeller Center. One priority had been to coordinate efforts to interdict Axis mail. The Brits and the Americans came to an agreement in November, 1940 to coordinate the goal of seeing that all transatlantic mail would be channeled through Bermuda.

In January 1941, President Roosevelt’s State of the Union message very clearly addressed threats to the US and the Americas posed by fascist aggression:

“ . . . we are committed to full support of all those resolute peoples, everywhere, who are resisting aggression and are thereby keeping war away from our Hemisphere. By this support, we express our determination that the democratic cause shall prevail; and we strengthen the defense and the security of our own nation.”

FDR was unequivocally affirming American support – short of war – for Britain. Pan Am, flying the international mail under contract to the US government, would play its part.

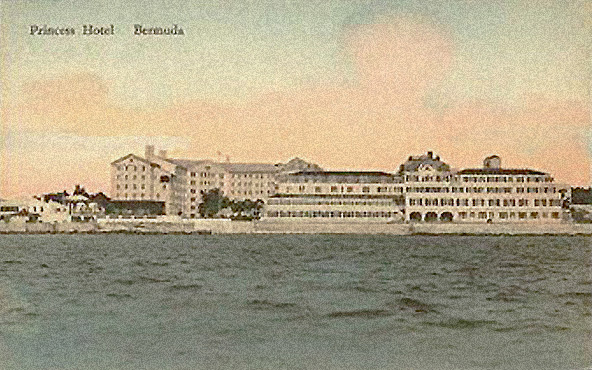

Soon the crew of censors in Bermuda had been expanded by hundreds of people, many of who came with specialized knowledge of unusual languages. With the same organizational spirit that would be evidenced in other British wartime efforts, they enlisted anyone, young or old, who might be in a position to lend a hand. They took over the famous Hamilton Princess Hotel, and the mission shifted from a somewhat ad hoc arrangement, to a full-blown enterprise of strategic national import. The censorship campaign even made a little money for the local Bermudan government, when confiscated parcels of food, and other valuables began to be auctioned off to the locals.

As far as Pan Am was concerned, it was just as well to concentrate on the core business of transoceanic transport. Cooperating with British authorities in their strategic mail censorship was another aspect of doing business in a world at war – a condition Pan Am was becoming increasingly familiar with across the globe.

Even after the U.S. was in the war for real, the clippers (now owned by and flying under contract to the government) would continue their regular flights there, and the tranquil island retained its status as a favored stop for seasoned travelers, where they were treated to the quiet pleasures of this most British of outposts.