Shortly after the end of the hostilities of World War II in 1945, Pan American Airways released a new film, “Clippers At War” to publicize the contributions made by the men and women of Pan Am to the victory just won.

In recognition of their effort as part of our national memory, we’ve adapted and excerpted sections of the description of the film, which emphasizes the magnificent logistical efforts made by the company and those who served. It should be noted that there were many Pan American Airways personnel who gave their lives during the conflict, starting with the very first day of America’s entry into the war, when Japanese aircraft attacked Wake Island. By war’s end, many others serving their country in Pan American’s wartime operations would pay the ultimate sacrifice, or suffer tremendous hardship as prisoners of war. We should remember that fact when reading the materials accompanying the film:

Excerpt from "Clippers At War" - the 1945 film that tells how Pan Am helped win World War Two (Pan Am Historical Foundation Collection)

FROM MATERIAL ACCOMPANYING THE FILM “CLIPPERS AT WAR”

The date was December 7, 1941. A secret message sent out across Pan Am’s global communication network read simply "Plan A". But its meaning was electrifying. This one-word and-one-letter message meant that war had come to the United States. Clipper crews and ground workers over Pan American’s more than 90,000 miles of routes throughout the world received the same message.

Every Clipper route was now a war route, and out over the ether through Pan American’s worldwide system of 239 radio stations, from New York to Singapore, operators relayed the orders of the Army and Navy. The Clippers of peace became Clippers at War.

Dodging Japanese Across the Pacific

Twenty-five hundred miles west of Pearl Harbor the Philippine Clipper had just left Wake for Guam when it received its war orders. In 20 minutes, Captain John Hamilton landed back at Wake. The Marine Commander asked him to take the Clipper in search of Jap planes or carriers. But before Captain Hamilton could get back to his Clipper, the terrible pounding of Wake was on. Japanese planes riddled the Philippine Clipper with 97 bullet holes, but couldn’t stop her. Carrying out the Commandant’s orders, Captain Hamilton stripped off all excess gear, and jammed 70 civilians into her cabin till the sides almost bulged. After three tries the Clipper staggered off the water, proceeded to Midway, Pearl Harbor and San Francisco, where her crew and passengers gave military intelligence officers the first eye-witness reports of the disaster at Pearl Harbor and the Wake and Midway bombings.

And Around the World

The Pacific Clipper was cut off near New Zealand. These Clippers—12 of them—were the only air- planes in the world capable of carrying a real load across an ocean. So the Pacific Clipper had to be saved for war service. Never before had a plane completed a long southern circuit of the globe. Never were the obstacles greater. But Captain Robert Ford and his crew did it. They took their huge flying boat across deserts and dangerous mountains, where she could not make an emergency landing, on a secret course by Australia, India, Arabia, Africa, the South Atlantic and Brazil to New York.

At Hong Kong

In Hong Kong the Japanese got the Hong Kong Clipper. And from that city, while docks, ships and tinder- box homes were still in flames, and Jap Zeros still nearby, Pan American’s partnership company, China National Aviation Corporation, flew to safety 275 officials and civilians, including Madame Sun Yat-sen and many of the country’s war leaders. They could make their flights only at night, under enemy fire, and through bad weather the Japanese couldn't fly in.

Back at their home bases, the silver Clippers quickly took on dull camouflage to blend with the night and the clouds. Maintenance jobs that took a day must be boiled down to an hour or two, to speed the Clippers off on faster and faster wartime schedules.

Women pitched in to help in the mechanical tasks. They donned mechanics’ uniforms, and released men for flight duty or work at overseas Clipper bases. They double-checked every detail of rubber lifeboats carried by the Clippers. These could spell the difference between life and death for men forced down at sea by enemy action. And the women inspected the hundreds of items provided in these boats—water containers, signal flares, kits of fish hooks, lines, bait, knives, sulfa drugs, vitamins, first aid kits and food.

At new wartime training schools, Pan American veterans passed on their knowledge to specially picked young men of the military services. Pan American men designed unique dummy control panels for training Navy personnel, and these reduced training which formerly required months to a matter of weeks. And the actual planes were out flying instead of tied up at docks for students to learn from their real controls.

Training Doolittle's Men

Five thousand cadets graduated from one of these schools,—the one for training young men in the new, rapidly developing science of aerial navigation. Some of the graduates were navigators on Major General Jimmy Doolittle’s smashing pioneer raid on Tokyo. At another Pan American school, Army and Navy flight crews learned radio communication.

The Eastman Kodak V-mail process was pioneered for airmail by Pan American and Britain’s Imperial Airways. At the start of the war this process was turned over lock, stock and barrel to the Army and Navy, to facilitate transmission of letters to our boys overseas. By photographic reduction, letters which formerly would have required all the lift and space of four Clippers were compressed into a few sacks that would stack away in a small corner on one Clipper

Two Hundred Gave Lives

There were many war heroes in the Pan American family. Two hundred gave their lives in performance of war duty. 45 more were interned in Japanese prison camps. And there were hundreds of heroic acts.

For example, Captain William Moss landed his Clipper in 15-foot shark-infested seas, and rescued 48 survivors of a sinking troopship. Captain John Hamilton was forced down in mid-Pacific, went through a 42-hour ordeal in 20-foot swells, yet brought his Navy transport plane safely to Honolulu.

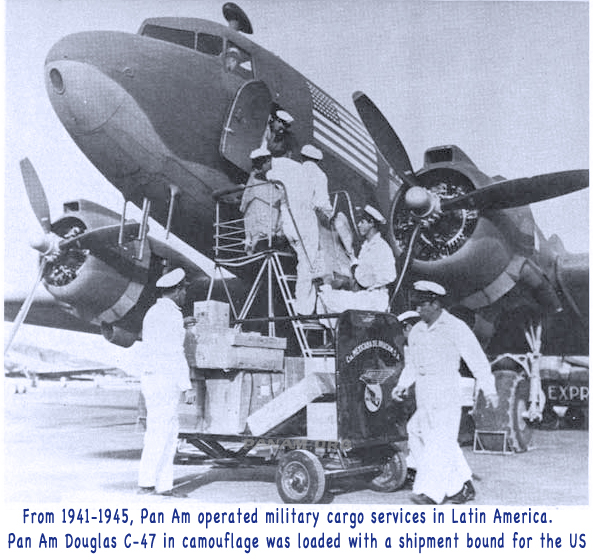

We had to have rubber, one of the most precious strategic materials of World War II. The Japanese seized the great Malay rubber plantations. So the Allies turned to Brazil’s great Amazon jungles, where the richest rubber trade formerly flourished. Jungle natives paddled canoes loaded with crude rubber. From the most re- mote tributaries of the huge Amazon basin, the rubber converged to the river’s main branches, where it was hoisted aboard Pan American amphibian planes that could alight on either land or water. From more than a thousand miles up in Brazil’s deepest jungle, these planes rushed their cargo to the Pan American airport at Belem, at the mouth of the Amazon.

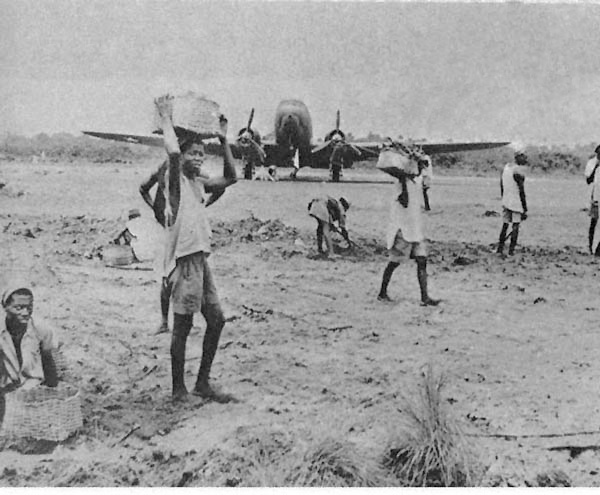

Airports in the Roughest Country

Possibly the most tremendous undertaking by Pan American in World War II was construction of a system of airports throughout the world, often in some of the roughest country known to man. The chain of more than 50 airports in 18 different countries turned out to be a vital weapon of the United Nations. They served thousands and thousands of our bombers and supply planes which dashed across the South Atlantic to blast the Nazis out of Africa, then on to smash the Axis armies out of Europe and Imperial Japanese forces in Asia.

Kicking Rommel Back From El Alamein

The African airway was established and service began 61 days after President Roosevelt indicated the military need for it. The bases could service huge bombers and transports in and out in less than an hour. And over the completed air lifeline, Pan American flew the very guns and cartridges that helped kick Rommel back from El Alamein. These war supplies were credited by General Montgomery with turning the tide, and driving the Axis out of Africa and the Mediterranean, and saving the vital Suez Canal.

Worst Flying in the World

Five thousand miles east of Suez, Pan American threw a wartime aerial highway over the treacherous Himalayas, from India to Chungking, China and beyond, through the worst flying in the world. When the Japanese cut the Burma Road as a highway for plodding motor trucks, the new routes became the very lifeline that kept China in the war.

Pan American’s young American and Chinese fliers battled the fiercest storms and severest icing, over jungle valleys and past ice-capped Mt. Everest, highest mountain in the world. Uncharted mountains would loom out of cloudbanks just ahead. Radios had to be silenced to avoid detection by the crafty enemy. And pilots often sought out the bad weather, in order to dodge death-dealing enemy fighters. Each plane did the work of 90 trucks on the old Burma Road. These planes, unarmed and unaided, held the line across the Himalayan Hump for 18 months, until the Air Transport Command of the Army Air Forces moved in with its great fleet of cargo carriers.

By the end of the war, many of these Pan American men flying the Himalayas had dodged through the clouds and around 20,000 foot peaks between India and China 500 times. More than 35,000 crossings had been made.

Carrying the World's Wartime Leaders

Pan American made more than 700 special flights which secretly carried the world’s wartime leaders to the conclaves at Casablanca and Cairo and on hundreds of other special missions. The routes of these special flights criss-crossed the entire world, and supplemented the 90,000 miles of Pan American’s regular routes.

Pan American did the biggest overseas flying job of any airline contractor to the armed services during World War II. When the conflict ended it was the largest air transport contractor to the War Department, and the only such contractor to the Navy.

The Cannonball

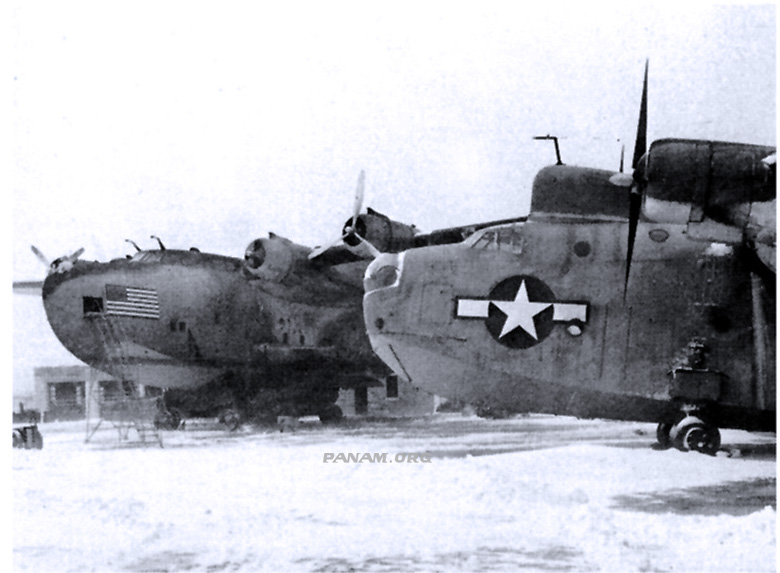

The Army overnight assigned Pan American to set up the longest and fastest big-scale air transport route to date, the 11,500 mile Cannonball run from Miami to India. To do this job, the company established an entire new Division, known as Africa-Orient. This division opened its service with a spectacular mass flight of five four-engined landplanes across the South Atlantic in November, 1942, near the time of the first United States invasion of Africa. Africa-Orient pioneered in breaking in the C-54 Skymaster airplane, which later became the big world-encircling workhorse of the Army’s Air Transport Command, and the other wartime contract airlines.

More than 100 specially trained flight crews regularly checked out of Miami, to fly the four-engined Skymasters on a record-breaking regular schedule of 3 to 4 days to the Orient. The Cannonball was virtually shooting supplies to India, Burma and China, and to the B-29 raiders of Tokyo.

Four Times Over Atlantic in Four Days

To keep the big Cannonball aircraft on schedule, flight crews sometimes stayed on the job 40 hours at a time with no rest. Some men flew the Atlantic four times in four days.

Africa-Orient’s mid-Atlantic route has been perhaps the most tremendous air transport operation ever conducted by a commercial airline—in number of big airplanes, and totals of passengers and cargo carried.

But because of the secret nature of Africa-Orient’s operations, little was known of its work. The men got no publicity, no medals or glory. Yet no ordeal was too great for them. The supply line they kept open was one of America’s secret weapons.

Illustrating the magnitude of Africa-Orient, it was announced that on September 22, 1944, sixteen four-engined Pan American Airways contract-operated C-54s were flying over the ocean on schedule at one time. And before the end of the war, Africa-Orient was operating an even larger land airplane, the Lockheed Constellation.

Fifteen Thousand Times Across the Ocean

During World War II, Pan American Airways made more than 15,000 ocean crossings. Of these 9500 were complete crossings of the Atlantic. The rest were over the Pacific. For many months Pan American averaged 17 crossings a day.

By 1945, Pan American had completed the astounding total of well over 346,000,000 miles. Always looking forward, Pan American was expecting delivery soon of even larger, faster and more economical air- craft, which will break more records, and greatly increase the speed, and slash the cost of overseas air travel.

We have told you in Clippers at War just a little of the story of the bravery, loyalty and teamwork of Pan American men and women in World War II. There were 25.000 of them at first, and they increased to 88,000. To all parts of the globe, over the victory routes they pioneered, they flew to the fronts where our boys gave their lives so democracy could live.

The wartime Clippers carried men and supplies over boundless oceans, across almost insurmountable mountain barriers, over uncharted jungle wastes, where few men had flown before. And it is a continuing story of men battling the dreaded hazards of jungle and desert, to stay on the job and keep the air lifelines open - yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Now that victory has been won, the wartime trails which Pan American blazed to the world’s most distant lands have become America’s great peacetime air highways. And Pan American will continue to pioneer and to lead in ushering in a new era - in which greater and speedier Clippers will cut through the smooth stratosphere - to carry America’s trade and America’s travelers, on their missions of peaceful commerce and good will, and to keep America first on the airways of the world.