ONE LONG DAY - ONE DARK NIGHT

The Final Flight of Stephen Dunn

An Experienced Pilot

Pilot Stephen Dunn was one of Panagra’s most experienced airmen. He came to the airline by way of the US Navy, where he had enlisted at age 17 in 1919, winning his wings at Pensacola in 1922. He left the Navy in 1930 to fly for the New York, Rio, and Buenos Aires Line (NYRBA), that only months later was absorbed into Pan Am. Dunn began flying for another new airline – Pan American-Grace (Panagra). By the summer of 1937, the thirty-five year-old was serving as Chief Pilot on Panagra’s Northern Division, which stretched between Panama and Talara, Peru. His job entailed flying as well as overseeing training and procedures for the other pilots in his division.

Stephen Dunn photo, Pan American Air Ways Magazine, 1932, PAHF Collection.

Sunday: A Long Delayed Takeoff

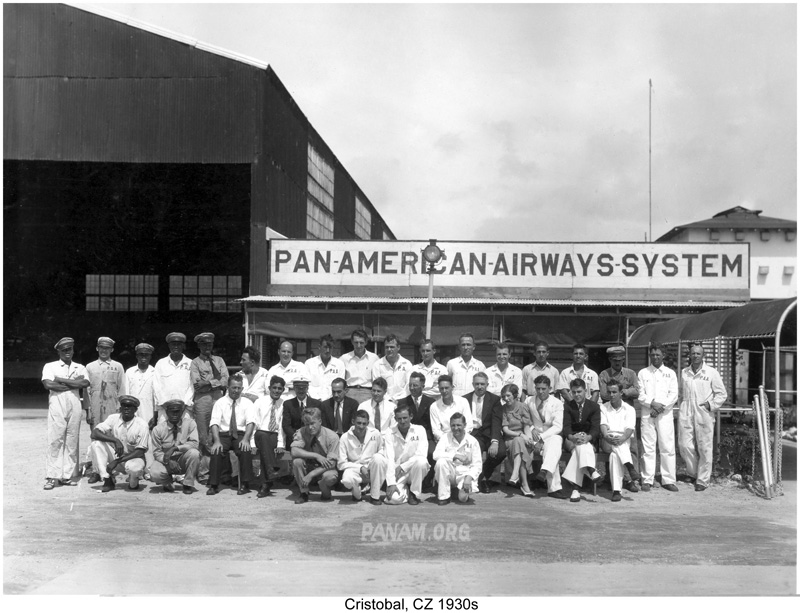

On Sunday, August 1, 1937, Captain Dunn along with a co-pilot/radio operator and a steward, was scheduled to fly a southbound flight to Guayaquil, Ecuador from France Field, the US military airport at Cristobal, in what was then the Panama Canal Zone, also shared by Pan Am and Panagra. The aircraft he would be flying was the “Santa Maria,” one of Panagra’s small fleet of Sikorsky S-43 flying boats. The relatively new twin-engine amphibian, registered as NC-15065, had been delivered to Panagra in May the year before, and was put into service the following month.

The Pan American terminal at France Field, Panama Canal Zone, ca. 1932 (PAHF Collection).

That day they missed their scheduled departure time of 4:30 am because the mail to be carried was not yet ready. In those years, US Post Office Foreign Airmail contract payments were vital to the airline’s bottom line. Panagra was paid for each shipment of mail carried. Passengers might miss their connection, but getting the mail on the flight was critical.

So it wasn’t until 11:40 am that they finally got into the air on their way south. They flew the S-43 as far as Cali, Colombia, but because of their late start, they overnighted there. They continued on to Guayaquil early the next day, making one 15-minute stop at Tumaco, Colombia on the way. It took about four hours flying time to reach the southern terminus of the trip. They arrived at Guayaquil at 10:15 am August 2nd.

A Panagra S-43 on the water at Tumaco, Colombia (Photo: PAHF / Banning Collection).

Monday: The Start of a Very Long Day

It turned out to be a very short turnaround for Captain Dunn. A mere 50 minutes later he was back in the air again, now retracing his steps in the same S-43, the “Santa Maria”, but with a new co-pilot and steward, heading back to Panama - a flight of 1,043 miles, scheduled for about eight hours in the air.

The route went back up to Tumaco -- a flight of two hours and ten minutes with a ten-minute stop, before setting off for Cali, another hour and 45 minute flight. The “Santa Maria” was on the ground at Cali for less than thirty minutes, and then it was off again for the last leg of the journey – Cristobal in Panama, about another four hours in the air.

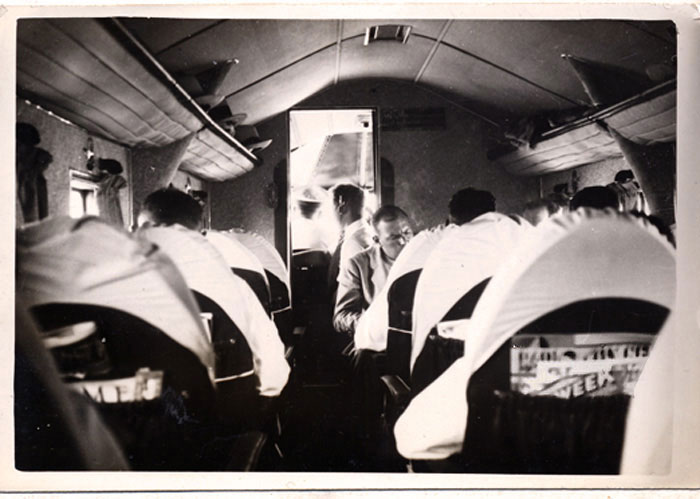

Interior view of a Pan Am Sikorsky S-43A Baby Clipper (PAHF Collection).

The ill-fated “Santa Maria” during a transfer of passengers to a Panagra DC-2.

(Photo taken from a Panagra promotional film, “South by Sky” / PAHF Collection).

Into a Dark and Stormy Night

The “Santa Maria” was now flying according to a major change in Panagra’s schedules, instituted only two weeks before. The airline now allowed flight schedules during night hours, a practice that up to this time had been avoided. Now the scheduled arrival in the Canal Zone would be 7:10 pm, half-an-hour after sunset – in the dark. There was no moon that night, but that would prove to be the least of Captain Dunn’s concerns.

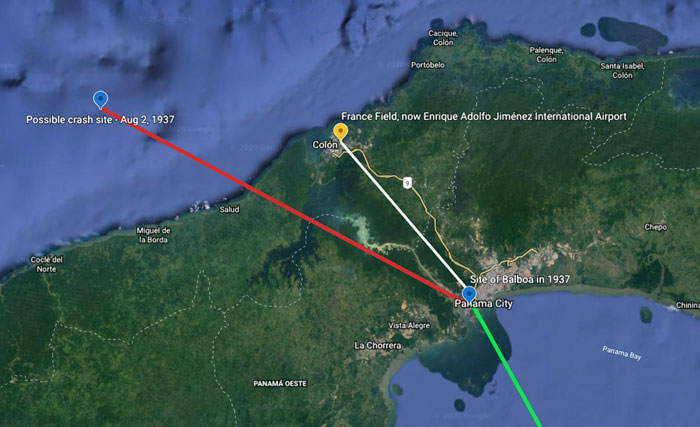

The Big Picture: "Santa Maria" flight path August 2, 1937.

During this last leg, Dunn (via morse code on the radio-telegraph operated by his co-pilot) kept in touch with the powerful US Navy radio station at Cristobal in Panama. At 4:30 pm, he reported the aircraft was at an altitude of 13,000 feet. The weather into which he was headed, he learned, was worsening: Overcast, ceiling 1,500 feet, and rain. At 5:00 pm he radioed that they were still flying at 13,000 feet.

Fifteen minutes later, Cristobal radio reported heavy rain, one-mile visibility, barometer falling, with a rain squall passing over France Field.

Then an hour later, about 6:15, the reports from Cristobal indicated an improvement in the weather: No rain now, ceiling at 2,500 feet, and visibility as much as 7 miles to unlimited. “Blue holes” were reported seen in the clouds off to the west.

But Dunn was flying in or above clouds, and unsure of his location. At 6:54 he asked Cristobal radio to check with the station at Balboa, located at the other side of the Panamanian Isthmus at the eastern end of the canal, if they could hear his motors. Two minutes later, they radioed in response: “Use more power – squall moving in over France Field.” Three minutes later, Cristobal advised Dunn that people on the ground at Balboa could not hear his motors: “Too much thunder.”

Possible final flight path of the “Santa Maria,” August 2, 1937.

Dunn was approaching his destination from the eastern side of the Isthmus of Panama, over the Gulf of Panama. (A geographical note: The Isthmus of Panama is bent like a gooseneck where the Panama Canal is located. In a quirk of geography, the Pacific is to the east of the Caribbean Sea here.)

Dunn had to fly across the Isthmus to reach Cristobal, located on the shore of the Caribbean Sea. He knew the land he was flying over was hilly and studded with hazards for aircraft, and so kept to a safe altitude, still flying “blind” in and over cloud and rain. It must have been a tense time in the cockpit of the “Santa Maria.” Dunn needed to get down safely, but there was little help available from those on the ground.

7:00 pm - Dunn to Cristobal: One word, “Wait.” Three minutes later, Dunn to Cristobal: “Advise – what’s the wind at Cristobal?”

7:26 pm - Dunn started to radio Cristobal of his position, but stopped, and said: “Wait.”

7:32 - Dunn to Cristobal, “Standing by waiting for an opening to get down.”

7:37 - Dunn to Cristobal, “Spiraling down over water – believe over east coast.” (Another geographic note: the term “east coast” referred to that touching on the Caribbean Sea)

7:38 - Dunn to Cristobal: “Still spiraling down.”

That would be the last transmission heard from the “Santa Maria.” Continued calls from Cristobal radio to the S-43 went unanswered, all through the night.

Aftermath

On the following day, August 3d, US military as well as Pan Am and Panagra aircraft set out to find the Sikorsky and any sign of its occupants. Navy search planes spotted floating wreckage about 15 miles west of Cristobal, and it was assumed the debris had drifted about 20 miles over night. No trace of anyone on the plane was found, just a few slightly charred items and aircraft fragments.

Likely a US Navy P2Y Consolidated Patrol aircraft like this one that found the “Santa Maria’s” wreckage (US Navy photo).

A Bureau of Air Commerce Board was immediately empaneled and departed for the US Naval Base at Coco Solo in the Canal Zone to investigate the crash. They had little to go on, other than circumstantial information, such as the career histories of the pilot and co-pilot, Panagra’s operational procedures, the pertinent weather reports, the flight’s radio communications log, and aircraft maintenance and operational history of NC-15065, the doomed S-43.

US Naval Air Station Coco Solo, ca 1930s (photo US Navy).

This last area – the aircraft’s history – proved to yield more substance than the other areas. The “Santa Maria,” like a sister S-43 in Panagra’s fleet, had suffered fuel system problems. In particular, it was found that the system incorporated auxiliary fuel tanks that had faulty shut-off valves, due to an integral elastic cord that was prone to insufficiently closing off the fuel tank even when the control was properly set by the pilot. This could cause the system to suck in air, rather than fuel, if the tank was empty. This fault might cause the engines to quit suddenly – a true hazard.

There was no way of knowing if this was a factor in the crash, but it was considered as a possibility.

Apparently, human factors were not given much consideration in the Board’s deliberations. Stephen Dunn had been flying for nearly a solid twelve hours when he encountered very bad weather near his destination - hours of flying with two Pratt and Whitney Hornet engines pounding away only a few feet from where he was sitting during all that time - fatigue and tension would very likely have had an effect on his capabilities or judgment. Dunn also reported flying at 13,000 feet for extended periods as well – very likely without supplemental oxygen -- another potentially negative contributing factor.

The Board released its findings before the month of August was over. They stated that the immediate cause for the crash was due to the flying boat striking the water while flying at no less than 90 miles an hour, causing it to break up on impact. No blame was attached to Pilot Dunn, and his actions were judged to be proper under the circumstances.

But the particular circumstances of the accident were left as a matter of conjecture, which is just how the Accident Review Board left it. In their words “The specific contributing cause of this aircraft colliding with the water is beyond the knowledge of man.” The “Santa Maria,” its crew of three, and the eleven passengers were gone in an instant, sinking into the depths of the Caribbean Sea.

Hindsight

Perhaps the Air Commerce Board could have made more of the fact that France Field had no radio range. This system, already in use in the US, made it possible for pilots to locate their position through the transmission of directional radio signals from a ground station. Pilots called it “flying the beam.” Dunn plainly was trying to establish his location, by calling on people on the ground to listen for his engines. His aircraft was also equipped with a radio direction finder, and it was surmised that his co-pilot might have been using it to get a fix during the few minutes before their last radio transmission. However, this technique could not have provided adequate navigational precision under the circumstances.

In the Board’s report, they noted that a ground-based radio direction finder such as those that were widely installed at many Pan American bases was under construction at France Field at the time. If it had been operational that night, it might have made a critical difference in the “Santa Maria’s” flight.

And it was a supreme irony that one of the eleven passengers on this particular trip was Rex Martin, an official of the Bureau of Air Commerce. His job, up until a few months earlier, was overseeing the installation of radio ranges around the US. If one had been available that fateful night at France Field, it might well have helped guide Captain Dunn and those with him to a safe landing.

However, in the event, Stephen Dunn, unsure of his position other than that he was reasonably sure he was over water to the west of his destination, put the “Santa Maria” into a spiraling descent – in the dark - hoping to come out of the rain and clouds somewhere above the sea’s surface where he could establish his position and safely fly to the airport.

He might have been caught in a blinding downpour as the plane flew close to the surface, leaving him solely dependent on his altimeter reading. It’s conceivable, but very unlikely, that one or both of the S-43’s engines might have suddenly been starved of fuel owing to the previously mentioned faulty fuel system.

One can imagine Captain Dunn, keeping the aircraft in a spiraling descent in the dark and in cloud, flying “blind,” while constantly switching back and forth between his instruments and his view outside, watching for the water’s surface he knew he was approaching. Perhaps fatigue played a part, slowing his critical reflexes. As with most accidents, it was likely a compounding of factors, which in this case added up to a lethal outcome.

Given better ground-based navigational support, Dunn might not have needed to hunt for the surface in a potentially disorienting spiraling descent, but could have chosen a safer straight-in flight path. Were his co-pilot not multi-tasking with a radio-telegraph in the midst of a critical maneuver, he might have had less on his plate as the S-43 flew ever closer to the unseen sea below.

Captain Dunn’s Legacy

The real take-away from this tragic story shouldn’t be the failure of one flight to end safely. It’s really about the fact that Stephen Dunn, along with his colleagues who flew during those early years of commercial aviation, built up a successful air transport system with almost none of the modern technology that today’s pilots wouldn’t fly without:

Radar; modern ground-based aids to navigation; reliable aircraft and engines that can operate thousands of hours without failure; a ground organization supported by computerized networks; or even the regulatory structures that have evolved to ensure and promote the safest possible environment for flying.

Pilots like Stephen Dunn were very often out there all on their own.

These early pioneering aviators knitted together an international air network that relied heavily on their skill and abilities, and it was often a heavy lift. They often faced challenges that might seem almost mythic compared to those encountered today. Those Pan Am and Panagra crews safely completed far more flights than not. It’s a remarkable record and worth remembering, along with the incidences such as the crash of the “Santa Maria” that helped point the way towards safer skies we have today.